Dogs and human males are the only beings that suffer from prostate disease commonly. This is to our advantage, as dog enthusiasts, because much research has been done on prostate disease in dogs in an attempt to better understand it in humans.

The prostate is a gland that encircles the neck of the urinary bladder . Multiple small ducts penetrate the urethra at the site of the prostate, allowing prostatic fluid to intermix with spermatozoa as they are ejaculated, to create semen. Dogs have no other accessory sex glands and, therefore, no other source of seminal fluid; all fluid present in the ejaculate arises from the prostate. Prostatic fluid is secreted at all times, whether the dog is being used for breeding or not. Most accumulates in the urinary bladder and is voided with the urine. Some runs down the urethra and accumulates at the opening of the prepuce, forming the mass of greenish discharge that often is visible on intact male dogs.

Diagnostic tests used to determine if prostate disease is present and, if so, type and extent of that disease, are the same for all conditions. Rectal palpation of the prostate can be used to assess prostatic size, shape and consistency and to determine if the dog is painful when the prostate is manipulated. Because the prostate encircles the neck of the urinary bladder, which is freely movable between the pelvis and abdominal cavity, an enlarged prostate may pull the bladder too far into the abdomen to be palpable per rectum. Some extremely enlarged prostates can be felt on abdominal palpation, Radiography has been used historically as a diagnostic test for prostate disease but ultrasonography is the technique employed most often at this time. Ultrasonography allows the operator to look through the prostate and guides placement of the needle or biopsy instrument if samples are to be collected directly from the prostate (Figure 2). Because all the fluid in the ejaculate arises from the prostate, semen can be collected and samples submitted for culture and microscopic assessment. Specific results of these diagnostic tests will be described with each disease.

Measurement of proteins in serum, as is used in human medicine, has not been shown to be consistently effective either for diagnosis of canine prostate disease or for determination of adequacy of treatment. Prostate specific antigen (PSA), commonly tested in human males, is secreted in dogs but concentrations do not vary predictably with presence or absence of prostate disease. Blood testing is not a common component of prostate evaluation in dogs at this time.

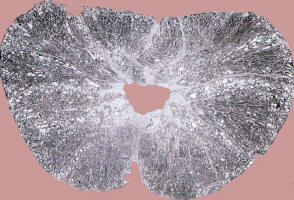

The predominant male reproductive hormone, testosterone, is metabolized in the body to form dihydrotestosterone (DHT). This secondary compound gradually causes an increase in size of the prostate gland such that all intact male dogs (and all human males) eventually have some degree of prostate enlargement. Prostate disease is fairly common in dogs, with a reported incidence of 2.5%. The average age at which prostate disease becomes clinically evident is 9 years. (Figure I – Prostate tissue, microscopic view. The central V-shaped area is the urethra) The prostate diseases most common in dogs are benign prostatic hypertrophy/hyperplasia (BPH), prostatitis and prostatic abscesses, prostatic cysts and prostatic neoplasia.

Benign Prostatic Hypertrophy/ Hyperplasia (Bph)

Benign prostatic enlargement consists of both hypertrophy (increase in size of prostatic cells) and hyperplasia (increase in number of prostatic cells). This occurs gradually with age and continuing exposure to the hormone DHT. In one study, 50% of dogs examined had some evidence of BPH by 4 to 5 years of age. Because this condition is dependent on continuing hormone secretion, it is seen only in intact dogs.

Many dogs with BPH show no clinical signs of disease. The most common clinical sign in dogs is dripping of bloody fluid from the penis unassociated with urination. Since prostatic fluid accumulates in the urinary bladder, bloody urine also may be seen. Occasionally, blood in the semen is the first problem noted by owners. In all other respects, dogs with BPH are normal. This differs from men, who are most likely to describe frequent passage of small amounts of urine as their primary complaint. Other signs that may be seen in dogs are referable to the greatly increased size of the prostate and include rectal tenesmus 9excessive straining to defecate) and subsequent passage of ribbon-shaped feces.

On rectal palpation, the prostate of dogs with BPH is symmetrically enlarged and non-painful. When examined by ultrasound, the prostate is enlarged but the tissue is uniform in appearance (Figure 3). The prostatic fluid, usually collected by manual ejaculation of the dog, is not inflammatory and semen cultures arc not significant.

No treatment is necessary for dogs with no clinical signs of BPH. The presence of BPH predisposes dogs to prostatitis so it should not be ignored; diagnostics for prostatitis should be performed periodically by your veterinarian (see below). Semen containing blood may be sufficient to effect pregnancy when bitches are bred by natural service or artificially inseminated with fresh semen but bloody semen should not be used for chilled or frozen semen, even if the sample is centrifuged and the bloody prostatic fluid removed immediately. Survival of spermatozoa ejaculated into bloody prostatic fluid is poor when those spermatozoa are stored for any length of time.

The best treatment is castration. Removal of the testes causes an abrupt decline in testosterone concentrations with subsequent lack of DHT. No medical therapy is as ef

fective as castration as a treatment for BPH.

For valuable breeding dogs, medical therapy may be necessary, at least until enough semen can be frozen to ensure the dog’s genetics are still available for future breedings. Herbal therapies used in humans, for example saw palmetto extract, have been shown not to be effective in dogs. Estrogen therapy has been described historically for treatment of BPH. The author does not recommend this therapy. While it may decrease clinical signs of BPH, it decreases the secretory function of the prostate, predisposing it to infection and may be detrimental to production of spermatozoa.

|

|

|

Figure 2 – Performance of ultrasound guided collection of cells from the prostate |

Progesterone therapy also has been described, with either injectable or oral forms of progesterone reported to effectively decrease prostate size and clinical signs of BPH without altering semen quality. Long-term progesterone therapy has not been described.

The drug therapy most recently described is use of finasteride, a human drug for BPH that acts by inhibiting formation of DHT from testosterone. ProscarTM is a 5 mg tablet of finasteride, approved for treatment of BPH in men. PropeciaTM is a 1 mg tablet of finasteride, approved for treatment of male pattern baldness in men, which also is due to DHT. Either medication can be used in dogs. Work done at the University of Minnesota and Washington State University by Dr. Kaitkanoke Sirinarumitr, Dr. Shirley Johnston and the author demonstrated that dogs with spontaneous BPH respond well to fairly low doses of this drug when treated for 1 to 4 months. The dose used was 0.1 to 0.5 mg/kg daily, which is one 5 mg tablet daily for dogs up to 50 kg in weight. There was no adverse effect on libido or semen quality. Humans are encouraged not to try to father children while on this drug. Studies have demonstrated no birth defects in pups sired by dogs on finasteride. It must be understood that BPH gradually will redevelop once finasteride therapy is withdrawn. Finasteride is the author’s medical treatment of choice for canine BPH.

Prostatitis / Prostatic Abscesses

Prostatitis is infection of the prostate. The reproductive and urinary tracts of dogs contain a certain number of bacteria at all times and the prostate is well designed to prevent movement of those bacteria into the gland. Any time infection of the prostate is identified, some underlying abnormality of the gland must be investigated. The most common condition underlying prostatitis is BPH. Because prostatitis occurs secondary to other conditions, it may be seen in intact or neutered dogs.

Acute prostatitis is recent infection. Dogs with acute prostatitis| often show pain when ejaculating and may cry out when urinating or defecating. They may have a fever with decreased appetite and poor attitude. On rectal palpation, the prostate is enlarged and may be asymmetrical and the dog shows signs of pain when it is compressed.

Chronic prostatitis is long-standing infection. These dogs feel well and often, poor semen quality is the only clue that infection may be present. Some dogs with chronic prostatitis present with recurring urinary tract infections as their only clinical sign. On rectal palpation, the prostate is enlarged, may be asymmetrical and is non-painful. This is the most common presentation of prostatic infection in dogs.

Prostatic abscesses are localized, walled-off areas of infection. They may cause significant asymmetry of the prostate on palpation. Dogs may appear healthy or may collapse with system-wide infection and shock if the abscess ruptures into the abdomen. Prostatic abscesses are uncommon.

Ultrasound may be useful in diagnosing prostatitis, especially if an abscess is present

|

Figure 3 – Ultrasound of a prostate with BPH |

|

Figure 4 – Ultrasound of a prostatic abscess. Note the circular dark area offset by white crosses. |

Most ultrasonongraphic changes seen in dogs with prostatitis are non-specific. Culture of seminal fluid or tissue aspirated directly from the prostate is the preferred diagnostic technique. Three types of cultures should be performed. Aerobic bacterial culture identifies those bacteria that live in air; these are the common names you know, such as E. coli and Strep. Because some bacteria are normal in the urethra, through which the semen flows during collection, some bacteria always will be cultured from a semen sample. A significant result is moderate to heavy growth of any single organism. Anaerobic bacterial culture identifies bacteria that cannot live in air; these are less common but cause more damage if they’re present. Mycoplasma culture identifies mycoplasmas and ureasplasmas, organisms related to bacteria. These are difficult to grow so the laboratory usually is unwilling to give your veterinarian an idea of quantity grown because they cannot differentiate low levels of growth due to technique problems from low levels in the sample from the dog. Because of this, it is difficult for your veterinarian to know the significance of mycoplasma results in all cases. If the author feels that a dog has prostatitis, based on all other parameters, and mycoplasma is the only organism grown, she will treat for it.

Antibiotic therapy is the primary treatment for prostatitis. The appropriate antibiotic must be chosen based on culture and sensitivity results; knowledge of the acuteness of the episode of prostatitis and information about movement of various antibiotics into the prostate gland. The prostate is surrounded with a tight capsule that effectively keeps antibiotics out of the prostate. In dogs with acute prostatitis, this capsule is functionally broken and any antibiotic will likely penetrate prostatic tissue well. In dogs with chronic prostatitis, an antibiotic must be chosen that can move through the prostatic capsule well. As a general rule, fluoroquinolone antibiotics (BaytrilTM, CiproTM) and trimcthroprim-sulfa antibiotics (PrimorTM) are effective against prostatitis. Owners should be aware that long-term use of trimethoprim-sulfa antibiotics may be associated with dry eye and/or anemia; concurrent administration of folic acid may decre

ase this effect,

Antibiotics must be administered for at least 3 to 4 weeks. Semen should be cultured one week and again one month after therapy to determine if infection is resolved. Therapy to combat the underlying cause of prostatitis, such as BPH, should occur at the same time. Once a dog has suffered from prostatitis, it is a good idea to recheck that dog with semen evaluation and semen culture every 6 months until he is castrated. Castration, and subsequent decrease in size of the prostate, greatly promotes resolution of infection. Prostatic abscesses usually are resolved surgically.

Prostatic Cysts

Two types of prostatic cysts have been described. True cysts, also called retention cysts, are accumulations of non-infected prostatic fluid in cystic spaces within the gland. Paraprostatic cysts are large, thin-walled, fluid-filled structures next to the prostate. With either condition, dogs may present with urinary tract signs (difficult urination, blood in the urine) or gastrointestinal signs (lack of appetite, abdominal distension). These are easily diagnosed by ultrasound and are resolved surgically. Prostatic cysts are uncommon.

Proslatic Neoplasia

Prostatic neoplasia, or cancer, always is malignant and aggressive. Usually by the time the owner has noted clinical signs, the cancer has spread from the prostate into the lungs or lymph nodes. In human males, prostatic neoplasia is hormone-dependent and hormone therapies have been described. Canine prostatic neoplasia is not hormone-dependent; in fact, several studies have identified castration as a risk factor for development of prostatic neoplasia in dogs although the increased risk of development of prostatic neoplasia is not so great as to outweigh the benefits of castration. Prostatic neoplasia is the only disorder that can cause significant prostate enlargement in a castrated male dog.

Because disease has spread by the time of diagnosis, dogs with prostatic neoplasia may present with any number of clinical signs including lameness, fatigue, coughing, difficulty urinating or defecating, or weight loss. The prostate is asymmetrically enlarged and very firm on rectal palpation and the dog may be painful as it is compressed.

Prognosis with this disease is poor, requiring your veterinarian to do a definitive diagnostic test. Ultrasonography sliould be performed to permit accurate collection of an aspirate or biopsy specimen to be submitted to a pathologist.

Treatment is palliative. Anti-inflammatory medications may make the animal more comfortable. Surgical removal of the prostate, as is performed in humans, is associated with many post-surgical complications including urinary and fecal incontinence in dogs and so is not routinely performed.

Prostate disease is common in dogs and those of you with intact males definitely will have to deal with it at some point. While it has some similarity with human prostate disease, significant differences exist, too, making it dangerous to try to extrapolate your own experience onto your affected dog. Ongoing research will help us better diagnose and manage prostate disease in dogs in the future.

This article is reprinted on this site with permission from the author.