Breeder/Exhibitor Ed, Conformation

(Learning is a process, not an event. An effective teaching experience combines the written and the interactive, refined by live observation.

As chairman of the DPCA Judges Education Committee I have a responsibility to inform the fancy of, in lay terms, how a judge interprets the Standard to select a winning Dobe.

I think it is important each fancier take the time to read the official Standard for the Doberman Pinscher. The Standard is available on the AKC and DPCA web sites.)

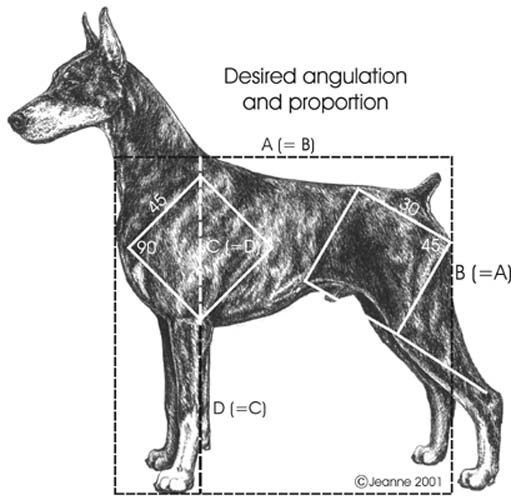

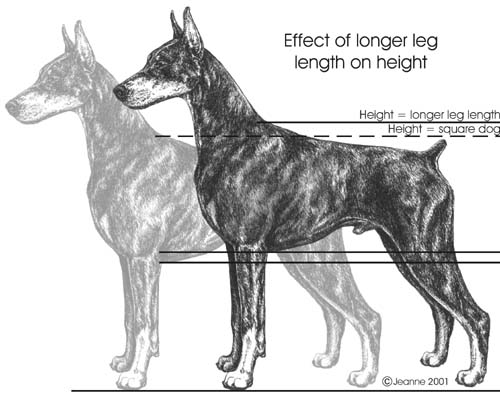

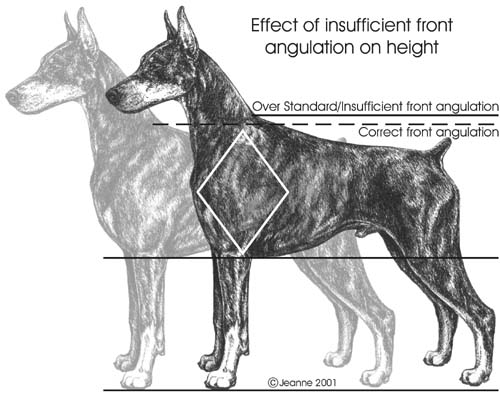

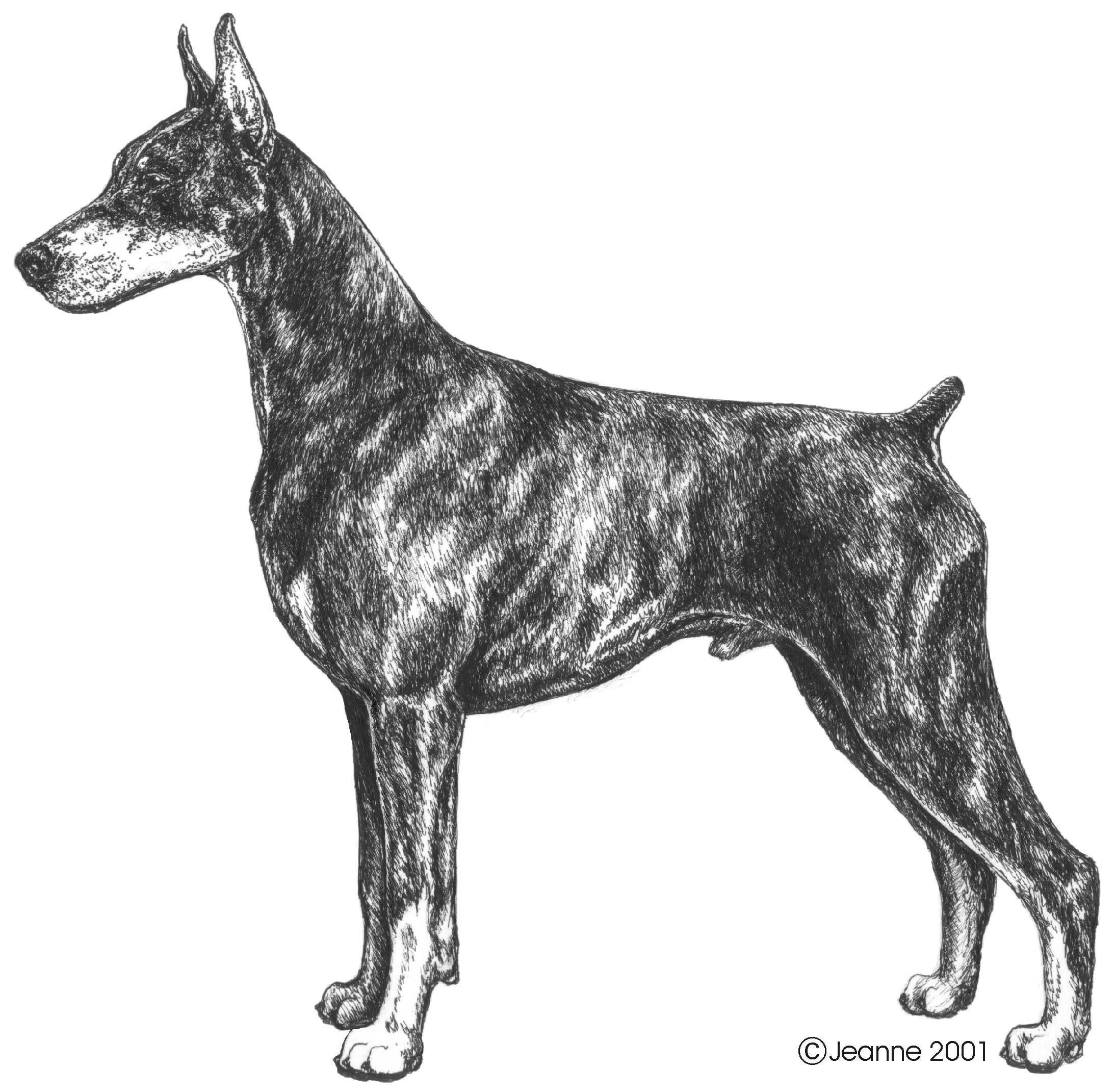

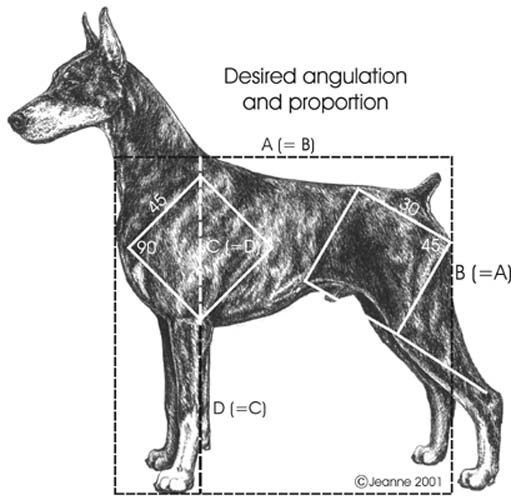

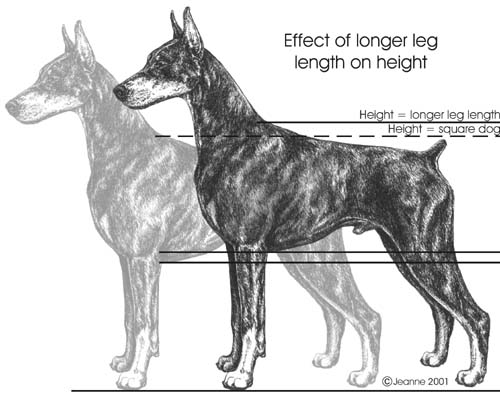

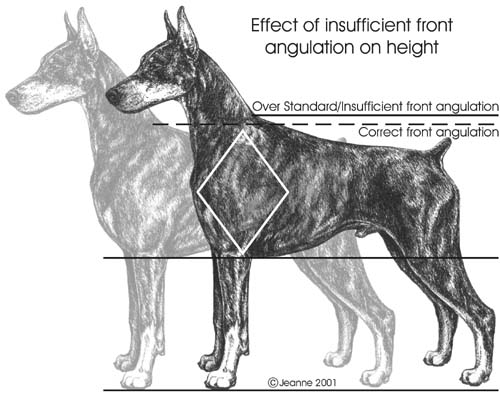

The judge’s first impression is the overall dog. Our Doberman handlers are some of the best in the world. They can make almost any dog look perfect in a stack, even to an experienced judge. The judge has only two and a half minutes to look at each dog so the well-presented dog has the advantage. Look for a square dog of medium size that is balanced. Does he have as much leg as depth of body? Is he deep to the elbows? Do his front angles match his rear angles? Is the length of the neck in proportion to the body and the head? Does his head look long but is it in proportion to the rest of the dog? Does he have heavy bone? Determine if the dog is powerful, elegant, alert, determined, muscular, and noble and is he compactly built. Many dogs have longer underlines than toplines. This can be caused by a straight upper arm which may cause a dog to look longer in length (more rectangular) than he actually is.

Having finished the initial observation, move the dogs in a group. Is anyone limping? Search for a fluid, powerful efficient gait that is balanced. Balance is very important and means that the gait generated by the rear drive is compatible with an equally angulated front to produce enough reach so the rear foot lands in the same spot as the front foot of the opposite side. Is the topline straight and smooth and does it hold while gaiting. Does the dog appear square or is it long in back or short in leg? Does it lack body? Check the tail carriage, it should be only slightly above the horizontal. Is the gaiting carriage proud?

Next is the individual examination where condition, attitude and show training come into play. Now is the time to reconfirm your initial side view impression with the overall dog. Approach the front; look at the head, breadth and depth of chest, and size and color of markings. Are the legs muscular and sinewy with heavy bone? Are the feet cat like? Place the head between your hands and look at expression. Is he stable, alert and confident? Feel the underjaw. Is the line from the skull to the muzzle unbroken and is it wedge shaped? Note the eyes for correct placement, shape, color and size. Are the ears set high? Is the skull too wide or too narrow, or just right? Looking from the side, view parallel planes and check for a slight stop, and depth of muzzle. Is the muzzle strong? Common deviations are snippy, pointy muzzles lacking underjaw, narrow heads that are not wedge shaped and round and/or light eyes.

The hands on examination is next. Check for muscle tone, placement and width of shoulders, snugness of elbows to body, and coat texture. Then, look at the rear, checking turn of stifle, equal length of upper and lower thigh, slightly rounded muscular croup, perpendicular hocks, and tailset. Look for a muscular rear, both on the inside and the outside of the legs, with parallel hocks set wide enough, where the front feet are seen just inside the rear feet. Is the rear cow hocked or bowed? Is the width of the hips equal to the width of the rib cage and shoulders? Is the dog slab sided (lack of rib spring) or barrel ribbed (too wide)? Are pasterns firm and almost perpendicular to the ground? Common deviations would be: shoulders that are set too far forward, straight shoulders, short upper arms, straight upper arms, lack of angulation – front or rear, long lower thigh, flat croup, high tail set, long loin, and lack of muscle in the upper thigh either on the inside or outside, as well as lack of muscle on the lower thigh.

The handler shows the mouth, or, if necessary, the judge opens the mouth. Count the teeth in groups, noting 42 correctly placed, strongly developed, white, teeth. The first group is the six incisors, the next group is the four canines (2 on each side, 1 upper, 1 lower) followed by the four premolars on the bottom and top of each side and the final group is the two top molars and three molars on the bottom of each side. Four or more missing teeth are a disqualification. The bite is checked. It should be a true scissors bite. Check to see if the bite is level, over or undershot. Overshot more than 3/16 inch and undershot more than 1/8 inch are disqualifications. Deviations are level bites, extra premolars, missing incisors, premolars and/or back molars, and poor occlusion.

Ask the handler to move the dog down and back on a loose lead, at a moderate pace. Watch the dog going around assessing side movement. Coming and going check for legs moving in a straight line. In the sound mover, the front legs are an extension of the shoulder and gradually converge towards the center as speed increases. Common deviations are moving too wide in front, too close in rear, side-winding, paddling, high stepping, loose elbows, flipping pasterns, and other inefficient gaits that prevent the dog from tireless, ground covering movement. Many times dogs do not move as well as they could because they are not in condition or are poorly trained. It is also difficult to evaluate a dog that is looking up at his handler or sniffing the ground. The well-conditioned and trained dog moves in a straight line down and back, with drive and determination. Many handlers cause their dogs to move inefficiently by using a tight lead. The dog on a loose lead moves best.

At the end of the down and back ask the handler to show the dog in a free stacked. Here is where the temperament and attitude meet with the judge’s toughest evaluation. In the free stack look for a dog who stands his ground confidently. As the judge moves around him he may flick an ear or turn his head to see who is there, but he remains calm and composed. The dog should be aware of the judge moving around him and not just fixed on the liver. At this point, you can see where he naturally puts his feet. The true topline, tailset, head and neck carriage are apparent. Put a lot of stock in dogs that exude energy, are alert and show fearlessness.

Upon completion of individual examinations, the final group is determined. If the class is eight or more, place the dogs in their tentative order. Then you move the class once or twice around and watch them stop. At this point, you can do another down and back with the top contenders, watching carefully how they stop. Then place the class. Many times exhibitors ask why the last down and back didn’t result in a change of placement. The reason is, in the final analysis, he moves well enough to confirm his win.

This is what a judge does in two and a half minutes in front of a partisan audience. No one ever said it was easy. Common sense indicates all judges have a specialty breed. All knowledge of other breeds is acquired knowledge, sometimes in the face of angry exhibitors.

What does this say about exhibiting purebred dogs? There is no perfect dog. The one picked at a particular show is the dog closest to the standard the judge has pictured in his mind of the ideal Doberman. A judge can only judge what is presented to him. The exhibitor must be patient. If he has a good dog, his time will come.

Breeder/Exhibitor Ed, Conformation

The Doberman Pinscher Club of America Judges´ Education Committee has received a number of concerns regarding the judging of our breed. Legendary breed authority Peggy Adamson said “our breed type emerges from the whole standard.”

Breeder/Exhibitor Ed, Conformation

Submitted by Bonnie Dunlop (Botrina Dobermans) and Marj Brooks (Manorie Dobermans)

What is a Champion?

A Champion is a dog (male or female) that has been evaluated by at least three schooled and licensed Judges as to how closely that particular dog meets the criteria (correct structure, movement, temperament, proportions and size, color) for the ideal specimen of the written Standard for that Breed. This dog would have been awarded the accumulative points needed to be awarded with a Champion Certificate by the AKC. Here is a link to the Doberman Pinscher Standard depicting the ideal Doberman: https://dpca.org/breed/breed-standard. The Standard is a guide to what the ideal Doberman should look and act like. Exhibits (dogs) are judged against individual breed standards which have been established for the AKC-recognized breeds by their parent clubs (Doberman Pinscher Club of America -DPCA).

How to Obtain a Conformation Championship

To obtain an AKC (American Kennel Club) Championship, each dog presented to a judge is exhibited (shown or handled) by its owner, breeder or a hired professional. The role of a professional handler is similar to that of a jockey who rides a horse around the track and hopefully, into the winner´s circle. “Professional handlers are just that – professional – they are talented at their craft. They can bring out all of your dogs attributes as if to bring the judges focus on these traits and are able to present the dog looking its absolute best to the judge. Many times they are able to have the dog to look more alert and watchful at the “right moment” in timing.”

Dogs in competition at conformation shows are competing for points towards their AKC Championship. It takes 15 points, including two majors (wins of three, four or five points) awarded by at least three different judges to become an American Kennel Club “Champion of Record.”

The number of championship points awarded at a show depends on the number of dogs (males) and females (bitches) of the breed actually in competition. The larger the entry, the greater number of points a male or female can win. The maximum number of points awarded a dog at any show is 5 points. Here is a link explaining how points are won and accumulated toward a Championship: http://www.akc.org/events/conformation/counting_points.cfm. Or http://www.akc.org/events/conformation/point_schedule.cfm.

Cost of entering a dog in any given show is $25.00 and up. Shows are held by different kennel clubs throughout the country and host a show under AKC (American Kennel Club) or CKC (Canadian Kennel Club) rules and regulations. Entries are paid to the show secretary for the kennel club hosting the shows. Some clubs have two shows on a weekend, others may hold three or four shows, so on average if there are 3 shows (Friday, Saturday and Sunday), then the entry fees will be $75.00 and upwards. Some show secretaries also are now charging a service fee to process entry forms. Those fees can range from $3.00 upwards which are added onto the cost of the entry fees.

If you hire a professional handler to show the dog for you, it will likely cost you from $65.00 to $90.00 per show. So if there are three shows you have entered the dog, you will be expected to pay your handler $195.00 – $270.00 plus taxes in some cases. Some handlers will have you sign a contract before they will show your dog.

Some handlers will write into their contracts that if they win the Breed with your dog or win a Group placement, you will be expected to pay the handler a set amount of money. It is like a bonus for winning. Even if it is not written into a contract, it is a gesture of appreciation and thanks to the handler for the prestigious win.

If you send your dog out of town to shows with a handler, then you must expect to pay additional expenses, such as a portion of gas, motel/hotel costs, meals, set-up expenses, etc. You will also be required to pay boarding fees for your dog if your dog is traveling with your handler as these costs pay for the food your dog will eat and is a reasonable request. The cost of traveling expenses is usually divided among all the other owners that the handler is showing for, so if the handlers traveling expenses amount to $800.00 for a weekend of showing and the handler was showing 8 dogs at the shows, then the cost of $800.00 would be divided by 8 to total an additional $100.00 on top of handling fees.

The total cost of obtaining a Championship on your dog can be anywhere from $ 1500.00 (if you show the dog yourself and finish in one or two weekends) upwards to approximately $10,000.00 to have the dog professionally shown, live with and travel with the handler.

Judges are schooled and licensed after studying the breed standard for which they choose to judge. Each judge will determine which dog closest meets the ideal specimen for its breed, based on how they interpret the standard and the ideal.

Different countries have different requirements for a Championship.

There is a relatively small percentage of all of the Doberman Pinschers shown that actually obtain a Championship. This is another criteria for the breeder to use to make breeding decisions based on the ideal.

Another criteria that breeding decisions should be made on the breeding pair is the DPCA (Doberman Pinscher Club of America) Working Aptitude Evaluation (WAE). https://dpca.org/awards/wae/. This is a valuable tool that tests the temperament traits as described in the Doberman Pinscher Standard. This is an article about the test and using it to make breeding decisions about the pair to be bred: Breeders Tools. Pay particular attention to the traits that a working Doberman should possess. Temperament should be part of the overall criteria for breeding decisions. The same is true for health test results to make sure breeding decisions are made to attempt to eradicate some of the diseases that plague our breed, thereby contributing to the future health and longevity of this breed.

Breeder/Exhibitor Ed, Conformation

by Hans Lehtinen & Chris Lummelampi

When we look at dog shows in general and competition at group level in particular, we are often struck by an all too frequent trend towards a convergence of breed characteristics especially when it comes to movement.

The question is: are we looking for an all-round show dog, flashy and sound enough, but not exactly epitomizing its breed type? Are we, as breeders and judges, tempted to ask for the same attributes on all show dogs, regardless of the breed? Movement is a measure of a dog’s conformation. If we accept what might be today’s barely perceptible changes in a dog’s movement, we may gradually allow an alteration in the breed type. We may, in fact, contribute to a situation where an Afghan Hound moves like a Poodle and a Poodle moves like an Afghan. If this is the case, then we need a serious discussion on typical movement in today’s show rings.

The original functions of many of our breeds have become obsolete as our societies have changed from agrarian into urban societies. Add to this the pressures to alter breed standards in order to breed “sounder” dogs — as if the existing breed standards were an impediment to sound dogs — and the emerging “green values” depreciating pure-bred dogs, and we may be distancing ourselves from true breed type.

When we look at the Poodle today, we hardly ever stop to think what the function of its long coat was as it performed its retrieving function in icy cold water: when the hair ends froze, the coat underneath formed an insulating layer keeping the dog warm; or that the Poodle clip with the hindquarters clipped short was part of maintaining the breed’s ability to function just as a colourful ribbon was tied to the dog’s topknot and tail to help the hunter see his dog out in the field. The Poodle’s movement also contributed to its usefulness as a retrieving dog: it was expected to move with the light, effortless gait which continues — or should continue — to be part of the Poodle’s breed type today.

No one expects the Brussels Griffon or the Yorkshire Terrier to catch rats in today’s urban environment, but surely this should not be a justification to change their original breed type. Neither do we expect the Shar Pei to function as a fighting dog, but this is no reason why it should not have enough fold of skin on its shoulders to enable it to turn, if gripped by an attacker.

In some breeds, function dictates movement. In others, there does not seem much logical explanation why a breed should move in a certain way — except when the movement is part of the breed’s heritage and deserves recognition. If the Fox Terrier heritage — or its standard, as the American one does in the case of the Smooth Fox Terrier — calls for the dog move its front legs like a pendulum of a clock, there is no reason why we should not appreciate this movement when we see it, however rare it might be today.

In the case of the “decorative” toy and utility breeds, the consideration of typical movement should not be any less important. We think of the Japanese Chin as a dainty dog who is expected to move with a graceful gait, lifting its feet high… or the Miniature Pinscher and Italian Greyhounds with their high-stepping Hackney gait, as required by the British and American standards. For Italian Greyhounds, the continental countries of the FCI used to have the same requirement, until the breed standard was abruptly changed by its country of origin to ask for “normal” movement.

You are, of course, entitled to ask how this can be accomplished without changing the front assembly of the breed — many of us do, especially as we wonder about some of the changes in the breed standards to accommodate the whims of the “country of origin.”

Although some of the breed standards drawn up by countries where the breeding of pure-bred livestock has not been a long tradition may leave lot to be desired, in some cases comparing the British, U.S. and FCI standards is a useful exercise. Take the Maltese standard. The British standard simply calls for free movement, whereas the original Italian standard describes what we have come to expect of a typical Maltese in motion: quick, short steps giving the impression of the dog sliding forward with its feet barely skimming the ground. Or compare the Poodle standards:the French one warns against the dog covering too much ground when it moves, but the American one calls for springy action — just as the Afghan standard does, although the movement of the two breeds could not be more different, with the Poodle waltzing around the ring in true “Poodley” fashion and the Afghan moving as if it had springs under its feet.

Variations in breed type in different continents also seem to play a role in our expectations of how a typical example of a breed should move. We see Shih Tzus in some parts of the world who would be much more at home in the Lhasa Apso ring, and vice versa. We hear a lot about the controversy surrounding their movement — flick-up or no flick-up for Lhasa, showing full pads for Shih Tzu — and lots of special expertise seem to be called for when assessing Lhasa’s “jaunty movement” when, in fact, it is a very moderate, normally constructed dog who should move with light feet, effortlessly like a trotting horse. Not so the lower-to-the-ground, heavier bodied Shih Tzu whose conformation (if correct) alone dictates that it cannot move with the same style as the higher-legged and differently shaped Lhasa.

Ideal Dog

All too often, we seem to be using the same yardstick to measure the quality of a dog, and we are too easily impressed with flashy showmanship and clever presentation. Someone once observed that, all too often, we believe a dog is a good mover if it covers the ground like a German Shepherd, comes and goes like a Beagle, and, to top it all, has the Setter topline, the animation of a Cocker Spaniel and the general attitude of a Poodle. Never mind if it is a typical example of its breed, epitomizing its written and unwritten breed standard. Never mind if its attitude is that of a composite, outgoing, animated show dog of no particular breed type, as long as it meets the generally accepted criteria for soundness… It will, no doubt, keep the Council of Europe happy and avoid scare headlines of “unhealthy” or “unsound” breeds of dogs. But it should raise alarm bells among us who work to maintain true breed type and who are convinced that we do not need take the Council’s at times misguided recommendations on “sound breeding principles” at face value — and we certainly do not need to take precipitated action to change our breeds standards to the extreme where a Brussels Griffon might suddenly be transformed into a reddish rough-coated Border Terrier. (Isn’t it rather that there is nothing much wrong with our breed standards from the soundness or health point of view — but there could be something wrong with our interpretation of these breed standards if we err on the side of exaggeration?)

It might be useful to look at the Pekingese standard which states:

“Slow, dignified rolling gait in front. Typical movement not to be confused with a roll caused by slackness of shoulders. Close action behind. Absolute soundness essential.” A Basset Hound with a sound, crooked front will move soundly – for its breed. Straighten the front legs, and you will get an unsound dog with a heavy body hanging between the front legs instead of being wrapped by them. A well-constructed but typical Chow Chow hindquarter, strong enough not to knuckle over, will allow the dog to move with its typical stilted gait, just as a typical, but sound construction will allow the Puli to move with a stride that is “not far-reaching. Gallop short. Typical movement short-stepping, very quick, in harmony with lively disposition. Movement never heavy, lethargic or lumbering.” The gait requirements of quite a number of breeds do not conform to the general conception of “sound dogs”, we

ll angulated in front and rear, moving with a ground-covering gait. There is no reason why they should, unless our aim is the identikit show dog.

The Faster the Better

It does not seem to be enough that most of our dogs move, and are often expected to move, in the same manner. They are also expected to move with the same speed regardless of the breed. Would a Rottweiler be a better, more invincible defender of its master and his property if it were to move with the same agility as an Australian Kelpie, a shepherd, running on the backs of the sheep in tight spots if needed to perform its function? Or would the St. Bernard be a better rescue dog in the Alps if it raced around the ring with the same effortlessness as a Saluki?

In fact, many of the so-called “rolling” breeds are moved around the ring so fast that they never have the opportunity to display their characteristic gait. Again, it might be useful to take a look at some of the breed standards. The Bulldog standard states: ” Peculiarly heavy and constrained (gait), appearing to skim the ground, running with one or other shoulder rather advanced.” Or the Clumber Spaniel: “Rolling gait attributable to long body and short legs. ” Or the Old English Sheepdog: “When walking, exhibits a bear-like roll from the rear…”

To mention a few more examples of typical gait: take a look at Cocker Spaniels and ask how often they display the typical bustling movement, or at Irish Water Spaniels whose typical movement is often described as that of a drunken sailor. Some Poodles and Spaniels are, it is alleged, moved so fast that their hind feet never touch the ground (not to mention that, nowadays, you hardly ever see the old-fashioned Cocker Spaniel movement…) In fairness, you could say that quite a few Terriers — and others, for that matter — are moved on such a tight lead that their front feet never touch the ground! “Hanging” dogs on tight leads may be appropriate when there is something wrong in the dog’s front and you want to reduce the weight on it, hopefully improving movement. This practice may not cause any major harm since it will certainly draw the judge’s attention to the problem. But it is unfortunate when dogs with excellent front movement are never allowed to show it to their advantage. It is also unfortunate that many breeds shown on tight leads show an unnatural or an untypical head carriage as handlers forget that the Deerhound or the Borzoi does not have the same outline in profile movement as the Afghan does.

Not all breeds of dogs were developed to be fast moving dogs. Note the American standard for the Alaskan Malamute which states: “In judging Malamutes, their function as a sledge dog for heavy freighting must be given consideration above all else… He isn’t intended as a racing sled dog designed to compete in speed trials with the smaller Northern breeds.”

Contrast this with the Siberian Husky whose required gait is quick and light on its feet. The Basset Hound, for its part, was originally bred to be a slow hunting dog to enable the hunter to follow him on foot without difficulty; therefore, a Basset with its true and deliberate movement should not be expected to compete in speed with the Sighthounds in the same group whose original function and style of working are entirely different.

Again, compare it with the smaller French hound, the Basset Fauve de Bretagne, whose movement differs from the heavier, low-to-the-ground Basset Hound because it .was created to work on a different terrain, in the thick undercover in Brittany.

Conditioning

All show dogs need exercise and conditioning beyond the few rounds around the show ring to keep them in top form and peak condition, and to enable them to present their typical movement to advantage. But the right exercise and proper muscle tone will never mask basic structural weaknesses or shortcomings in breed type. They will only enhance good, typical movement.

With coated breeds we, as breeders, exhibitors and judges often struggle to balance the show ring requirements of keeping the coat in top condition with the requirement to maintaining the dog underneath in peak physical condition with proper exercise. Often we end up with a flabby dogs with flowing coats, or well-muscled dogs with broken coats when we, in fact, should be looking for a happy medium. (One of the ironies of life is that some of the coated dogs who are kept in wire crates and exercise pens, as they often do in America, have wonderful muscles — could it be that they spend their days bouncing up and down in their crates?)

The same applies to other forms of technology which are being introduced into the world of show dogs. We need a happy medium between exercise machines, or treadmills, and other forms of exercise. Some blame poor front movement on the excessive use of treadmills, others tend to think that treadmill exercise, if used excessively, may constrict the dog’s movement by shortening its stride, resulting in a peculiar gait behind. Instead of condemning treadmills outright, it might be useful to see them as excellent aids in exercising dogs in adverse weather conditions when outside exercise is impossible, to be supplemented by other forms of exercise — walking, bicycling or letting the dogs gallop in the fields.

Not many of us can go as far as a famous Afghan Hound kennel in the U.S. where the dog runs include an L-shaped ring going up and down the hill, forcing the dogs to turn and stretch when they gallop. Nevertheless, versatility in exercise will ensure that the dog uses all its muscles to the full and is in peak condition.

But, to return to the point of this article, a dog, however well muscled and however well moving, is not a typical example of its breed if it does not have typical movement. And if we accept small changes in the movement of a breed, we accept small changes in conformation, proportions and overall breed type until we end up with an identikit show dog. (And talking about proportions — have you noticed how many of today’s show dogs are losing the length of leg?)

Understanding sound movement is important, but understanding typical movement is essential if we are to preserve breed type. Learning to quote the breed standard may not be enough, because, to paraphrase the late Tom Horner, any child can learn to recite the Lord’s Prayer, but understanding it will take years. Therefore, we should not be in too much a hurry.

Breeder/Exhibitor Ed, Conformation

written and submitted by Bill Garnett, USA

“the DOBERMAN PINSCHER is a square, compact, medium size dog of balanced proportions, noble in its carriage, courageous by nature and SOUND of mind, body and joints”

Recently I was talking to a good friend of mine about . . . what else? Dobermans! He’s been involved in the sport of pure bred dogs in general, including Dobermans, for many years. But more recently he has been showing (owner handling) his Labrador and doing a whale of job. He’s had “Ben” ranked around fourth or fifth, nationally, for the last couple of years. Not to take anything away from Mike’s handling . . . I do have to say “Ben” is a heck of a nice Lab.

Anyway, Mike and I have enjoyed many discussions regarding dogs in general and Dobermans in particular and he knows exactly where I stand regarding soundness and has for years agreed with me in that regard. But the other day he said something to me that really got me to set up and take notice. We were discussing Dobermans after he’d been on the Florida, Louisville and Raleigh circuits and Mike said to me. “You know Bill, the Doberman has lost it’s (type).” To which I said, “No Mike not you . . . not you too!” To which he said. “Now hear me out before you get all bent out of shape. Years ago soundness was very important because people were breeding to the correct concept that a Doberman was a square, compact, medium size dog, of balanced proportions. Type was in abundance and we looked to over all soundness to separate the wheat from the chaff. The only fly in the ointment, or if you will differences of opinion, in those days, was size. What has happened in the last decade, for whatever reason, is that Doberman people have just lost their way. They’ve gotten caught up in the old ‘what wins’ black hole . . . As to the ‘what’s right’ even blacker hole, they have traded proper breed type for the improper (typey) Doberman.” Why? In some ways it’s really not the breeders fault because today’s judges are going with the ‘typey’ Doberman instead of the ‘correct type’ Doberman . . . breeders usually do go with the flow. It’s a helluva lot easier than beating their heads against the wall. The ‘typey’ Doberman is long and low (rectangled), out of balance and lacks compactness. It’s ‘typey’ all right . . . but it’s the wrong (type).” He went on with his oratory such as only Mike can do, saying. “In order to correct this problem we have to buy into the standard and understand fundamental breed type. Fundamental (breed type) is reflected in dogs that are square, compact, medium sized and of balanced proportions.” Mike continued, “The buck stops with the judges. In order to correct this situation, of ‘typey’ winning over correct type, this is what Doberman judges need to do. First look at the class and if not physically, then mentally pull out the dogs of correct breed type . . . square, compact, medium sized and of balanced proportions. Line them up in order of how well they subscribe to the standard (square, compact, medium sized and of balanced proportions) and then go about picking out the soundest of that group.” Out of the mouth of babes!!!

You know what? Mike is right! Yes you heard what you thought you heard. Correct breed type has gone by the wayside. Now, before you get carried away and say that Garnett has finally overheated, don’t forget what I have been preaching for years. By adhering to the standard, proper breed type will manifest itself automatically when we breed . . . square, compact, medium sized dogs of balanced proportions that are noble in their carriage, courageous by their nature and sound of mind, body and joints. What we are going through now are ‘typey’ dogs that are long and low, certainly not square, certainly not of balanced proportions and certainly not compact. Because of those attributes these dogs are simply not sound either in their static or kinetic positions. Their fronts are too straight and too far forward. They flip, flop and pop all over the place. Because of their lack of balance they run up hill. And because of their over-angulated rears they crouch and run on their hocks. I just missed what really was going on because of the total lack of soundness that is being exhibited. Proper breed type has indeed strayed and has been replaced by improper (typey) Dobermans. It’s as simple as that. I just couldn’t see the forest for the trees.

I’m not going to argue the point with anyone so don’t bother to try and get me to take the bait. You either get it or you don’t. Either you pull your head out of the sand, take off your blinders and stop breeding whatever judges are willing to put up or you suck it up. admit to playing to the judges whims and do the right thing for the future of the breed. Its really that simple. If judges would hang tough, learn and then put up the correct breed type, within four years breeders would be back on the right track and the breed would be back on the high road.

Type vs. Typey…is there a difference? You bet it is. What are you going to do about it? What are we going to do about it. What am I going to do about it? I’ll tell you what I’m going to do about it. As a judge I pledge to recommit myself to being a part of a team that resurrects the correct breed type that’s manifested when one subscribes to breeding to the standard.

Breeder/Exhibitor Ed, Conformation

written and submitted by Bill Garnett

…Choose your poison

Some time ago I wrote about having heard about two handlers, who when asked to speak before a judge’s group, told that group of judges that type was the first and foremost consideration when evaluating Dobermans. They even went as far as to instruct the group that soundness was of little or no serious consequence . . . quote, unquote. It has got to look like a Doberman first . . . they advised. That was the first bleep on my radar screen that made me sit up and take notice and get me to thinking:

What did they mean, it has to look like a Doberman? I’ve been involved with Dobermans

for longer than I care to admit and have been judging them for almost twenty years and I have yet had a dog (Doberman) walk into my ring that I didn’t recognize as a Doberman. Admittedly some were better specimens than others but I had no problem recognizing them as to the breed they were. As a matter of fact when you have been involved with Dobermans as long as I have you develop a sense of recognizing them a long way off and I bet a lot of you can recognize a Doberman several blocks away. So what do you mean it has to look like a Doberman and you have to consider “type” before anything else? The Doberman Pinscher is a type . . . a “type” of dog!

I have to admit that it was a puzzlement to me for years . . . this thing called type and over the years I realized that I’ve heard the word type used in many different ways when describing a Doberman . . . enough to confuse the most ardent of fanciers.

- He is my type.

- He is not my type.

- I like that type.

- I don’t like that type.

- She’s really typey.

- She doesn’t have good type.

- I like the showy type.

- I like the big type or

- I don’t like the little type

…and on and on it goes to where finally we have reached a point where everybody has a type. What the heck is going on with this thing called type? And then it hit me. The type that everyone is talking about is not really type at all . . . it’s hype . . . or better yet it’s called personal preference and what they are really doing is hyping their personal preference under the guise of type.

For what reason and why is this happening? Finally it hit me. It’s pretty simple! It creates several scenarios:

- First it benefits the personal preference crowd in that it justifies their breeding program’s lack of soundness.

- Secondly it creates enough confusion and a venue where the poorly informed judges and the weak minded have excuses as to why they put up those un-sound dogs.

I once had a judge tell me that he liked his dogs to look like dogs. Another told me that she liked her bitches to look like bitches. Still another said he liked a lot of bone and substance. Another liked the high stationed look. Another liked good down and back. And still another like strong side movement and etc. Each time I would hear one of these personal preferences I shuddered and would wonder to myself why no one ever mentions they want their Dobermans to conform to the Breed Standard by being balanced, sound and processing the symmetry that only a standard conforming Doberman would have and those with a good eye could appreciate.

In an attempt to rationalize their ignorance of the standard many have implied that the standard says little about a Doberman being sound or as the two handlers said . . . “soundness is of little or no serious consequence.”

Either those people haven’t read the standard or if they have, they have absolutely no understanding of the concepts it imparts for the standard from beginning to end calls for and demands an orderly and harmonious arrangement of parts to create a statically and kinetically balanced dog. It even acts as a blueprint, instructing us on just how to do so. The problem that raises it’s ugly head is that a lot of us won’t read or can’t understand the blueprint (standard) for whatever reason. Think how difficult it would be to build a house if one wouldn’t read, or for that matter couldn’t understand, a blueprint.

I’m sure that with pure gall some of us would get something up but for how long would structural integrity be present . . . if at all? By applying a shiny coat of paint, called type, hype or personal preference, I’m sure that some could convince others that structural soundness was present. That same analogy has been popping up in Dobermans for quite some time. Too few people understand or for that matter bother to read the blueprint (standard) and too many have buckets of paint, glossing over the important stuff, bluffing their way along, intimidating those who know even less . . . painting everything in sight. The color is called type, hype or personal preference and it’s guaranteed to cover all faults in one coat. It’s even accepted, as I said earlier, as an excuse for those that breed and exhibit Dobermans that are un-sound but are charismatic, showy, do tricks and back-flips for a piece of bait and ask for wins.

On a more serious note if we allow soundness, that which is so methodically outlined in the Doberman standard, to be circumvented in the name of type, hype or personal preference, not only will we be acting irresponsibly but we could be culpable to contributing to the decimation of another breed of dog. Today, the Monks in New York are having to import their breeding stock to get correctly conformed Shepherds. Cockers can no longer go to field and Irish setters can’t even find the field. All this has happened because our judges are being influenced in the name of hyped/type which simply translates to personal preference. We no longer require working dogs to be sound enough to work, sporting dogs agile enough to hunt or herding dogs balanced enough to herd. If we don’t know how and we refuse to learn to read the blueprint (standard), if standard conforming Dobermans are of no interest to us, then we should go fly kites, collect baseball cards, become millionaires, be astronauts, captains of industries, whatever! If those alternatives are of no interest and we must stay involved in Dobermans, please let’s spread as little of our “hyped/type” or “personal preference” as possible.

If you have only learned one thing from reading what I have written I would hope that it would be the following analogy:

The Doberman does have a type and it is manifested when we adhere to the Doberman standard. It’s not my type nor your type nor his or her type it’s called proper breed type. Once you’ve seen and understand the balance, symmetry and soundness of proper breed type you won’t settle for less.

“The DOBERMAN PINSCHER is a square, compact, medium size dog of balanced proportions, noble in it’s intent, courageous by nature and SOUND of mind, body and joints. If you should be so fortunate as to find two dogs possessing these nine traits then by all means break the tie with any of your personal preferences” .

Breeder/Exhibitor Ed, Conformation

- Article written and submitted by Colby Homer, Homer Hill Dobermans

- Illustrations by Jeanne Flora, Argostar Dobermans

|

|

|

© Jeanne 2001

|

Preface

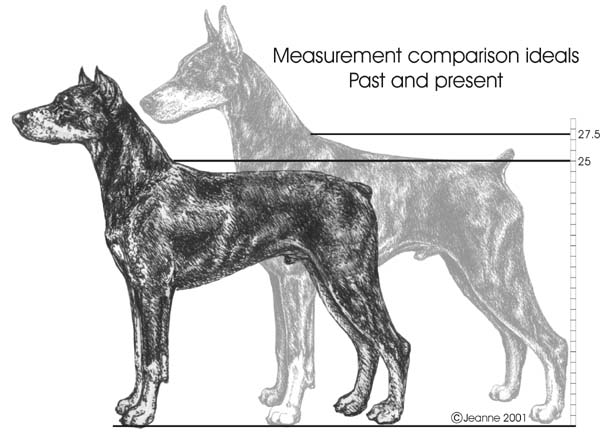

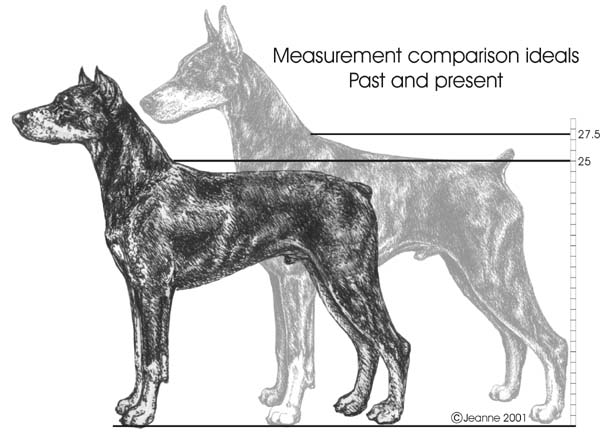

- When I became involved with Dobermans in the 1970’s I was taught by my mentors that measuring your own dogs was a necessary part of their assessment. It was interesting and enjoyable to track their growth as puppies and it revealed that some of my dogs added a bit to their growth rather late in their maturing process. Since I knew my dogs’ height I casually compared them to others at show, just as all of us trend to do.While showing what would become my first owner-handled champion, under Peggy Adamson, a comment she made to me as she handed me the ribbon changed my attitude in regard to size from an observer to a student. Peggy put her hand on my arm, smiled and simply said “You know, your dog is really lovely … but just a little too tall for me”. She was correct, of course, as he was 28-3/4-inches and since I respected her so much, that simple comment made me want to find out why it mattered to her.

As years went by there were other dogs and a few (very few!) litters and I was pleased to manage to stay with standard-sized animals. It was particularly satisfying to finish a 25-inch bitch, in twenty shows from first point to last, myself and to have a 25-3/4-inch bitch that I bred and co-owned, achieve an Award Of Merit at our National in her only outing as a Special.

I bring this anecdotal history to paper so the reader can understand that I have owned over-sized animals and animals well within the Standard and finished both and felt them both worthy of finishing. I can well appreciate the commitment of a breeder and owner bringing a quality Doberman Pinscher to the point where he is evaluated in the ring as show and breeding stock. I have written this article solely with a desire to sharpen awareness and stimulate a discussion of our breeders, owners and judges, regarding the element of proper size in the Doberman and how to assess it from several perspectives.

With that said, I also must comment that at this time I am observing a larger percentage of bitches being exhibited that are well over standard size. With most of our male dogs over standard or at the top of our Standard, the trend of larger bitches could possibly defeat our natural system of checks and balances within our breed for size when breeding. When one breeds an oversize dog to an oversize bitch, after all, what size will the majority of the puppies be at maturity and what are the consequences of those breeding decisions be on the future gene pool?

I have drawn on the expertise of those known to us, as well as some experts outside our breed, for this article. I was encouraged by the consensus of opinion generally being with my own.

With all of this in mind, here are some of the ‘Whys Of Standard Size’.

From the Standard for the Doberman Pinscher:

‘Size, Proportion, Substance – Height at withers: Dogs 26 to 28 inches, ideal about 27-1/2 inches; Bitches 24 to 26 inches, ideal about 25-1/2 inches The height measured vertically from the ground to the highest point of the withers, equalling the length measured horizontally from the forechest to the rear projection of the upper thigh. Length of head, neck and legs in proportion to length and depth of body.’

|

|

|

© Jeanne 2001

|

- Introduction

- As we all know, several important and highly detailed books cover the origin and early history of the Doberman (check Bibliography). Some of these books are ancient history but still remain a ‘must read’ for anyone that is truly serious about our chosen breed. History makes today’s progress discernable and yesterday’s concerns are highly relevant to today’s concerns. Although ours is a young breed compared to others, researching one aspect over a hundred years was a project that could have been easily expanded to a chapter in a book. This is a brief overview of just one part of Doberman structure…size…but it is certainly one of the most essential aspects of the Standard.

To better understand the present we must review the past. For brevity, some highlights follow in a ‘time machine’!

On August 27, 1899, the National Doberman Pinscher Club was organized in Apolda, Germany and the first Standard of the breed was issued. In 1900 the Doberman was recognized as a breed in Germany. In 1908, the first Doberman was registered in the United States. The first American Champion was Ch. Doberman Hertha in 1912. By 1920 there was a Doberman entry at Westminster and by 1923 the Westminster Doberman entry was 46. Early Doberman people in the U.S. spared no expense and important dogs and bitches were imported from Germany and Holland. Further proof of their dedication was that they brought German experts over to judge as well. Philipp Gruenig, one of the greatest historians of our breed, judged Dobermans at the March, 1927 show of the Long Island Kennel Club and in a statement in the AKC Gazette said “The correct size of the male is 25-1/2 to 27 inches. The bitches may be smaller. Statements in some American dog magazines that the maximum height of a Doberman is 25-1/2 inches, I think they may be wrong. The tendency for some years has been toward the larger dog. On the other hand, this should not be carried to excess”. (2) To step back in time just a bit, we see Gruenig’s critiques were prefaced by the 1925 Standard which finally mentioned ideal size and included under faults ‘Especially faulty…too low standing or distinct high-legged’, the first cautionary comment regarding size. With the breed in such rapid evolution, type was stabilizing, so size was the next concern … or was it the beginning of a controversy? as we can see by the photos (and note the dates) the Doberman changed and grew larger at an amazing rate! By examining the chart ‘Size Limitations In The Dobe Standards Throughout The History Of The Breed’ (3) one can easily see the drama unfolding. The only material change that took place between the years of 1899 and 1925 (in the Standards), was an increased shoulder height for dogs from a minimum of 21.6 inches to a maximum of 23.6 inches, corresponding with a maximum of 18.8 inches to 21.6 inches for bitches. The breed grew taller which necessitated a concession as to shoulder height. Controversies over the maximum shoulder heights extended over a number of years. The conservatives felt that inasmuch as the Doberman Pinscher belonged to the medium-sized breeds, it would be dangerous to permit such heights as 27 inches for dogs and 25 inches for bitches respectively, because it might easily happen over the course of time that the breed would not cease growing — by continuous use of tall animals — and consequently the Doberman would lose the main essentials of a medium-sized dog.

| SIZE LIMITATIONS IN THE DOBE STANDARDS THROUGHOUT THE HISTORY OF THE BREED |

|

compiled by Thomas Tyler Skrentny, MD

|

|

|

|

|

|

Ideal |

| Year |

Where Adopted |

Males |

Females |

Males |

Females |

|

| 1899 |

Germany & America |

21.6″ – 23.6″* |

18.8″ – 21.6″ |

none given |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 1920 |

Germany & America |

22.8″ – 25.6″ |

21.6″ – 23.6″ |

none given |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 1925 |

Germany & America |

23.8″ – 26.2″ |

22.3″ – 24.2+” |

25″ |

23.1″ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 1935 |

Germany & America |

24″ – 27″ |

23″ – 25″ |

25.6″ |

24.4″ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 1948 |

America |

26″ – 28″ |

24″ – 26″ |

27″ |

25.5″ |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 1958 |

America |

26″ – 28″ |

24″ – 2″ |

27.5″ |

25.5″ |

|

|

*This is also given as (21.6″ to 25.6″) in the Doberman Pinscher in America by Schmidt. In the third edition of the Doberman Pinscher by Schmidt (21.6″ to 23.6″) is given and is probably correct since both maximum and minimum were changed with each new standard on all other occasions. 25.6″ in 1899 would have been unchanged in 1920, which is unlikely.

|

|

|

|

© Jeanne 2001

|

The radicals took the opposite stand. They claimed that so long as the Doberman developed into a larger dog, it would be unfair to exclude otherwise outstanding specimens on account of narrow height limitations. The latter group won its argument! William Sidney Schmidt – 1926 (4)

So it became clear that two of our earliest experts, both of whom were a great influence on America’s earliest Doberman owners and breeders, were sharply divided on the issue of size! There are some comments in both Gruenig’s and Schmidt’s books that some of the earliest imports to the United States, although of high quality, were available only because of their being oversized! This is further substantiated by the article ‘What Is Inherited’ by Eleanor Carpenter (Jerry Run – breeder of Demetrius’ dam) (5) who provided a specific example of Cherloc v Rauhfelsen, sire of Ch. Jessy v.d. Sonnenhoehe (1934), being sold specifically because he was 28″. Jessy was surely the most important dam of her time with tremendous influence on the Dobermans of the United States. At a DPCA National sometime during the 1940’s the membership was polled at the annual meeting and 80% had dogs related to Jessy. She produced Ch. Ferry v Raulfelsen , the first Doberman to go Best In Show at Westminster (1939), just three weeks after his arrival from Germany. While making her home in America, Jessy produced Ch. Favoriet v Franzhof and Ch. Alcor v Milsdod, two of the seven sires researched by Peggy Adamson to be the basis of nearly all significant breeding in American Dobermans. World War II solidified this base of important stud dogs since no more imports were possible.

The earliest if these sires, Ch Westphalia’s Rameses, was whelped in 1938. Ch. Domossi of Marienland and Ch. Westphalia’s Uranus in 1939. In 1941, Ch. Emporer of Marienland, Ch. Favoriet v Franzhof, Ch. Alcor v Milsdod and lastly Ch. Dictator v Glenhugel, were whelped. An interesting point made by Peggy in her article ‘Illena And The Seven Sires’ (6) (Illena being the notable dam Ch. Dow’s Illena of Marienland) is that Illena and the youngest four of the Seven Sires were sired by the older three, except for Dictator who was Domossi’s younger full brother. To quote from the article; ‘Five of the Seven Sires were between 27-1/2″ and 28″ in height, Rameses being slightly over 28″ and Domossi slightly under 27″.’ Peggy goes on to say; ‘During the ten years prior to August, 1951, a total of 416 Dobermans completed their championships in the United States. One half of these were descendants in the first, second or third generation of the Seven Sires. One third of the total number were their own sons and daughters (139), 62 were grandchildren and 7 were great-grandchildren. (6)

So, history class is over and we now understand that by looking at the earliest history of the breed we see that the Doberman Pinscher has the innate ability to get taller rapidly unless held in check by selective breeding. We also see that some of the early Dobermans that were imported into America were oversized and most of the Seven Sires, a major part of our early gene pool, were near or at the top of the Standard. By communicating with some of the most respected elders in our breed I learned that there were drastically oversized dogs finished and oversized Dobermans were often winning over properly sized ones in every era.

Sometimes this really caused an uproar; I’ve included a couple of letters below, one of which was very controversial in its day. In the last twenty-five years or so size discussions have become fewer and with the influx of many new judges (more every month) and many new people owning, exhibiting and breeding Dobermans without the benefit of mentors, size is not the issue it should be.

|

SHOW NOTES

|

|

DETROIT SHOW

|

From the various reports we have received the Detroit Show seems to have been a huge success . . . I quote a letter from one of the spectators . . .

“The outstanding thing about the Detroit Show this year was the general quality of the Dobermans exhibited. It was said by many people present at both shows that the quality in the Specials class at the Doberman’s Sportsman’s Club Show far excelled that of Westminster. Much comment at the ringside was that the average height of the dogs was at least an inch less than at Westminster and it still approached the top of the Standard. Lack of quality is not necessarily the consequence of breeding large dogs. The difficulty lies in the fact that some breeders prefer size to quality.”

“Open bitches was one of outstanding quality throughout. The class was one of the best four bitches I have seen at any one show (exclusive of Specials Class) in two years.

Specials Class showed true fighting spirit. Every dog, without exception, required lots of room. Mr. Arthur O. Tischer did a very fine job of judging.”

This last sentence the editor can subscribe to for I have seen Arthur Tischer judge quite a few shows and turn in a good job each time. He has and deserves a reputation for ‘placing them as he sees them’. |

|

|

|

|

SIZE

|

| There has recently been a controversy over the question of size. There are those who believe that the standard was written to be a guide to judges when judging Dobes. There are those who think the Standard was written to be a guide to breeders in selecting an ideal of perfection. There are those who believe the Standard was written to satisfy the requirements of the American Kennel Club. Some believe that 28 inches can be stretched to 31. Some imagine that a 95 pound Dobe is capable of running!! Everyone, however, is in agreement on one point. That is, that a bitch 23 inches high, never shall, never could, win Best of Breed at a five point show. Some think perhaps she should win, but everyone who is not kidding himself knows that no such thing will happen. |

|

K. E. Smith

|

- from Dobe News – June 1949

|

I had this article in mind for quite a long time when I read the following which certainly expresses why one would question the importance of size: “It boils down to a question that has been around for many years — do you breed in order to produce a better, more nearly perfect dog according to the Breed Standard and history and function of the breed — or to produce dogs that will win at dog shows? Everyone says they want to breed ‘better’ dogs — ‘better’ for what purpose? Is winning a lot of colorful ribbons really proof that the exhibit is, truly, closest to the ideal of the breed? Too often I have heard people state that they would forgive faults in construction as long as the dog had the ‘attitude’ that would make it a winner. This includes breeders, exhibitors and judges — including some breeder judges. (7)

So why are we still struggling with size? Or are we bothering? One theory that may be worth considering is that from the time of the Seven Sires there were several influential and astute breeders who created carefully crafted pedigrees that resulted in animals that ‘bred true’ to various attributes predictably. With these ‘gold standard’ breeders one could bring an animal to their line to improve certain virtues.

Although it is possible that size will always be considered a ‘renegade factor’ and genetically unpredictable, size was certainly more predictable by breeding to or from the animals of these accomplished breeders. Today, very few bloodlines remain tightly line bred for generations and many breeders do not have the background information to choose for proper size when evaluating a litter. By the time a promising puppy is ready for the ring size is no longer relevant to the owner exhibiting the dog. There is no disqualification for size in Dobermans, promoted as a good idea in the past and nearly made mandatory; in fact, size discussions outside of seminars, are rare. With no disqualification, dogs and bitches, with heights at the top of the Standard and over, are the norm for Dobermans of today, with many well over. The lower half of the standard height in Dobermans are not commonly seen in the ring. With this complacency firmly in place many judges today do not see the additional virtue of a correctly sized Doberman and are often confused by them. The unfortunate part is that so many of the wrong kind of examples are in the ring and winning, that judges (and exhibitors) begin to see those as being correct — and begin to look for them and reward them. This has a devastating effect on the breed as a whole (at least to ‘purists’ — many others probably accept it as ‘progress’). I expect that this is true in many other breeds as well. Popularity in the show ring seems to have that effect. (8)

It may be interesting to contemplate that without careful attention to size, primary breeding motivation today may just be to perpetuate characteristics necessary for success in the conformation ring, irregardless of what they were historically created to do. Size is a functional attribute; think of the visual contrast in the ability of the Great Dane and the Doberman to reach a gallop quickly and corner efficiently and the necessity of this ability to be in an agile, medium-sized dog used for agility, fly ball, advanced obedience and other working sports, including service dogs. All of us are just as pleased if a Dobe that carries our name gains an agility title or an obedience title, so by making size an important consideration when making those lengthy pre-breeding evaluations, we could theoretically improve our chances of our dogs being in easier reach of multiple titles … a Dobe for all reasons!

The form versus function adage should still ring true in the mindset of the serious Doberman breeder, owner and our most learned of judges; the type versus soundness checklist debate is studied and discussed in every judging seminar; but do judges and breeders recognize breed evolution (a positive and necessary process) versus breed exaggeration? The all too human desire to be accepted can be especially prevalent in judging and we know it is easy for judges to follow the winning dogs today by simply opening their mailbox at home and viewing the masses of dog magazines automatically sent to them. It can be difficult to stick to the ideology of proportion and size standards if a judge is not sure they are any longer in ‘vogue’ and everyone knows a ‘renegade’ judge doesn’t judge often! Does a typical, dare I say ‘average’ judge, go into a ring today determined to find, in 2-1/2 minutes, the most correct animal according to our Standard? Or does he ‘go with the flow’, so to speak, and judge amongst the most prevalent type brought before him, ignoring those that may appear ‘out of type’? A scenario frequently witnessed is that of a correctly sized dog with good parts and kinetic soundness standing in a sea of oversized Dobermans who doesn’t get recognized for his additional virtues. I think few would argue that this scenario is now even more frequent in bitches.

Yet we do continue to produce dogs that amass amazing records and provide a strong impact on the awareness of the conformation community at large; it is wonderful and gratifying, that in the Top 20 Working Dogs, year after year, multiple Dobermans are listed and the top Working Dog of all was a Doberman, etc., etc. I sincerely congratulate each and every one … in some aspects you set the bar for achievement! I would be remiss if I did not also say, with emphasis, that some of our most famous were the most correct!

But, as I said earlier, how do we recognize the difference between breed evolution and breed exaggeration? Being the quintessential American show dog (or at least near the top) we are, in general, amongst the best handled, conditioned and promoted breed anywhere. Ambitious owners and ambitious handlers are making such an impact … but are our Dobermans ‘morphing’ into a beautiful ‘Generic Show Dog’? Did you know Dobermans are always named as one of the prototypes of the outline invading many breeds? To paraphrase a general description of the ‘Generic American Show Dog’; oversized animals with the generic outline that wins today … upright animals with sweeping side gait (and handlers going faster to match it), too short bodies (yes, its possible in a square breed), unbalanced angulation front to rear with the resultant sloping topline and too much length hip to hock completing the profile, and of course with a lot of daylight underneath. Extreme example? Certainly. Possible? Definitely!

But I digress to make a point … how do we keep progressive yet remain cognizant of our breed’s purpose and origin? Surely a topic for discussion, but part of the answer is to strive to keep the Doberman Pinscher a medium-sized dog through the only means available that has any influence … good breeding decisions and good judging decisions.

The purpose of this article was to encourage self education and discussion of the various aspects that influence size. I bring to this writing twenty-six years of serious study and observation … in and out of the ring and the whelping box. During these years I was privileged to have the opportunity to question some of our past and present Doberman experts and the one thing I constantly remind myself of is that one can never learn enough! With that in mind, I compiled a questionnaire that I sent to expert judges of our great breed that are particularly cognizant of proper size. The following are the questions and their replies and I want to express my appreciation to George Rood, Anthony DiNardo, Bill Garnett and Frank Grover for their kind participation.

1. Do you feel there are sufficient educational materials available to educate new judges on correct size and how to evaluate it?

- George Rood

- I believe that sufficient information is available to the new judge provided he/she is interested enough to procure it. The illustrated Doberman Standard would be a good start.

- Dr. Anthony DiNardo

- There are not presently sufficient adequate educational materials available to educate new judges on correct size and how to evaluate it. I hope that we can get the DPCA to produce an Illustrated Commentary on the Doberman Pinscher. This would help to educate the new judges and Doberman Pinscher enthusiasts.

- Bill Garnett

- Lack of educational material is not the problem. All one needs to do is read the standard just once. It is explicit in its instruction … males 26 to 28 inches, 27-1/2 being the ideal. Bitches 24 to 26, with 25-1/2 being ideal. You can’t be any more clearer than that. So why should there be a problem? You know the answer as well as I. Some judges just don’t seem to take the standards seriously enough or they’re poorly schooled, easily intimidated or playing games.

- Frank Grover

- No, such materials are not readily available. Reasons oversize in our breed is a serious problem have been published many times in the last sixty odd years but the judging techniques have not been pulled together and explained in communication instruments aimed at helping new judges.

- The basis of judges education is the Standard for the breed. Its role in the AKC dog show structure is to guide or govern the judge in the ring in much the same way laws govern or guide the judge in civil or criminal courts. In AKC organizational design, the preparation and safeguarding of the Standard is the primary responsibility of the parent club … in our case, the DPCA. The Constitution of the parent club requires each member of the DPCA to support the breed Standard as the only valid expression of the breed ideal. Judges should know it and know how to apply it. In fact, any serious exhibitor should know it. Height specifications in the Standard are clearly stated and how variations in height should be handled in evaluation is set. (1) Ideal height for a Doberman Pinscher is: if a dog, 27-1/2 inches; if a bitch, 25-1/2 inches. The Standard also states the height range within which all mature Dobermans should stand. It is 26-28 inches for dogs; 24 – 26 inches for bitches. Any dog or bitch not within this height range is to be penalized doubly … for deviation from the ideal and for not being within the normal or acceptable height for the breed … thus the penalty for a dog that is 28-1/2 inches is greater than the penalty for a 26-1/2 inch dog, though each is the same numerical distance from the ideal. That extra half an inch over 28 is more seriously a deviation from the ideal than an inch or even an inch and a half under the ideal.

-

To apply this, a judge must learn to identify heights of Doberman Pinschers accurately and to have a well set sense of how much to penalize each deviation. A pamphlet with an accompanying video could explain the key concepts and demonstrate the skills a judge needs to be able to estimate and evaluate each Doberman’s height by the Standard. A simple device to add to a yardstick could make practicing measuring easy and reasonable. Such a device could be available.

2. Do you have techniques or helpful tips on how to assess size while judging?

- George Rood

- Standing erect measure the distance from the floor to your hand. Some women have placed a safety pin on their clothing at the proper height.

- Dr. Anthony DiNardo

- I believe all judges must develop an eye for heights. I have instilled in my mind’s eye what I believe to be 25″ and 28″. Practice, Practice and Practice. I believe we all tend to perceive a dog’s height to be slightly taller than their true height.

- Bill Garnett

- Well, first of all, at the risk of sounding immodest, I’m blessed with an eye. Most of the time I can tell right off the bat if a dog exceeds the Standard … height wise. However, on the close calls, I have a way collaborating my suspicion. If I stand up straight with my right arm extended down my side, the measurement from the tip of my index finger to the ground is exactly 27-1/2 inches. With that to fall back on I usually know exactly what I’m dealing with. I do find I double check bitches more than dogs. Borderline cases in dogs are really no factor and anyone that can stay away from being run over by a bus should be able to recognize a 29 inch dog … I think?

- Frank Grover

- The most essential tip is prepare. To judge by eye, a person must recognize a 27-1/2 inch male Doberman Pinscher and a 25-1/2 inch bitch … and recognize which males are over 28 inches and which bitches are over 26 inches. A judge must also establish a penalty system for deviation from the ideal and for dogs and bitches that exceed the normal height limits for the breed. These two skills should be practiced in advance.

The second tip is that a judge check estimates while in the ring. (Official measurements are not made because there is no disqualification) Though the judge should practice to recognize ideal height and excessive height, verification in the ring can be useful. Years ago most Specialty Judges of Dobermans employed marks (pins, thread or other marks on their clothing) to check estimates in the ring. This can still be done. Measuring points on your leg or with your fingers when they touch the withers as you stand upright can also become quite useful checks.

Another way to establish height checks in the ring is to look for objects when planning ring patterns. Table legs, ring markers, even chairs can be used. Establish marks for the key heights (24, 25-1/2, 26, 27-1/2 and 28) on the selected object. In examination, have each Doberman stand next to the object in such a way as to be able to note height.

3. Do you find that regional type exists in respect to size?

- George Rood

- Size differs in certain parts of the country, usually due to increased usage of a popular stud.

- Dr. Anthony DiNardo

- Heights of Doberman Pinschers does vary in different regions. This may be due to the predominance of get from a certain line or stud dog. In general our breed tends to have more dogs that are above the desired height rather than dogs that are on the low end of the Standard.

- Bill Garnett

- I used to but not anymore. In the past several years I have judged all over the country and have found Dobermans to be overall standard conforming when it comes to the issue of size/. Now that condition might be brought on by the fact that people do their homework and know that I’m looking for standard conforming dogs, not only as they relate to size but how they relate to the overall standard as well. By now, people that know the Standard and have a standard conforming dog, know or should know, to show under me.

- Frank Grover

- Yes. However, the Standard of the breed applies in all AKC shows.

4. Overall, do you observe that there are more oversized dogs or bitches being exhibited? Is oversize more prevalent now?

- George Rood

- A gradual increase in size seems to be occurring. When asked to choose between a small dog and a large one most choose the large. I have heard judges say they will never put up a dog under the Standard but will take one over the Standard.

- Dr. Anthony DiNardo

- From my experience I have found that I more females that are above the ideal height of 25-1/2″ than males over the ideal height of 27-1/2″. Judges seem to forget that there are sex characteristics and will accept the females as large as the males.

- Bill Garnett

- Boy that’s a great question! I don’t think there is any doubt about it. As they relate to the Standard’s exacting parameters bitches are exceeding the size requirements more so than the males. Why? As in any debate there are several arguments. In this case, the first one is somewhat long in its explanation, but harbours some reality. I’ll try to cut to the chafe and make the explanation as short as possible. Although both are over the Standard’s parameters, a 27″ bitch will probably be in better balance than a 29″ male. Now follow me closely. It gets a little technical and you have to have an understanding of balance. Let’s take a 29″ male and a 27″ bitch and study the comparison. A male that is 29″ has to distribute balance over a framework (or square) that is 2″ larger than the 27″ bitch and in most cases nature doesn’t distribute that 2″ evenly. This will usually result in throwing the 29″ male out of static and/or kinetic balance. So, in terms of overall balance, the 27″ bitch will appear more standard conforming. Even though she may be oversized, that balance enables her to slip under the radar screen at times undetected.

The other explanation or contributing factor for explaining why bitches, for the most part, seem to exceed the standard more so than dogs completely enrages me. There are those that have taken it upon themselves to perpetuate the notion that if you are going to campaign a bitch special … better she be big than standard. Their explanation is that she’ll stand out in the group ring if she’s bigger. If this is true, then group judges that fall prey to this kind of logic should have their group licenses revoked. They are supposed to evaluate each breed as to how closely it conforms to it’s standard and award placements based on that evaluation. An oversized Doberman bitch is not conforming to one of the most important aspects of the breed standard and it is my opinion she should not be considered for group placements.

- Frank Grover

- Thinking back, in the fifties and sixties many huge males won in shows. Thirty-two inch males were shown as Specials at the Nationals. In the 70’s a commercial kennel advertised at stud a 34-inch champion. Today, males of such extreme size are not seen in our shows or if they are, they aren’t apt to win. However, most of our mature males that are shown are over the ideal and far too many exceed the height limits for the breed.

Some of the beautiful bitches being shown and winning exceed 26 inches by from one to two inches and more. Twenty-eight inch bitches win in major competitions and sometimes Best In Shows. This writer is under the impression that we are showing and winning with more over-height bitches than males.

5. Which do you consider more serious, an oversize dog or bitch? Why?

- George Rood

- An oversize dog is less desirable than an oversize bitch in my opinion.

- Dr. Anthony DiNardo

- Both the oversized dog and bitch are equally improper. However, a judge must remember that an oversized dog portrays itself as being a ‘LARGE’ breed whereas an oversize bitch may still be within the realm of the ‘MEDIUM’ size breed.

- Bill Garnett

- In terms of the Standard both are considered to be faulty in that area and therefore both are discredited proportionately by the degree of that fault. An oversized bitch should not be any more acceptable than an oversized male and vice versa.

- Frank Grover

- When judging, the seriousness of oversize is not determined by the sex but by the amount of the oversize in the individual animal. Each should be evaluated for the degree of variation from the ideal.

As far as the breeder is concerned, having a beautiful bitch that is substantially oversized is more serious for it is hard to locate correct sized males to use with such bitches.

As far as the genetic influence is concerned, it is hard to say. The traditional size control from the German breeders was to keep the bitches within the height limits. Breeders in other European countries bred larger bitches but never to large males. Geneticists with whom I have made inquiries have indicated that height and size are very complex studies but given little guidance. One very influential man in the breed objected to stress on size. It was his assertion that it would take care of itself. Unfortunately, it hasn’t.

6. Please discuss the importance of a judge rewarding standard size.

- George Rood

- The obligation of the judge is to award the class to the entry most nearly fitting the standard. This decision is of the utmost importance.

- Dr. Anthony DiNardo

- The importance of judges rewarding the Standard Size Doberman Pinscher is one of the most significant statements that they could make for the breed. With the increase of height the breed does not have the corresponding increase in bone so as not to appear more refined. As the breed approaches the size of a large breed, in the majority of instances, the breed loses the attributes which attracted many to this medium sized breed (stamina, bone, substance, angles, endurance, square, energetic, agility, etc.).

- Bill Garnett

- The Doberman is a medium size companion dog. The very first sentence of the Doberman Standard calls for a medium size dog. Its not somewhere down the line buried in some meaningless paragraph of minutes. The very first sentence mind you! The Standard is steadfast in it’s declaration. The Doberman is not a BIG dog … it’s not a LITTLE dog … it’s a MEDIUM size dog. And the Standard later sets exacting parameters in terms of both dogs and bitches by instructing us using language of exact measurements. How important is it? It may arguably be the single most important statement in the whole Standard. The DOBERMAN PINSCHER is a medium size dog. To answer your question as to how important size is … let me put it to you this way. To think that a judge would enter the ring to evaluate Dobermans and not have the size requirement as one of his or her more important breed characteristics that he or she is looking for … is unconscionable.

- Frank Grover

- If by standard size you mean a dog that is of ideal size, any dog with a part as described in the Standard as ideal should be recognized … and that should include ideal height. Of course it is the whole dog that the judge evaluates and places; in the evaluation, the perfect parts are recognized and admired while the deviations from perfection or the ideal are noted and penalized.

If by standard size you mean a dog within the size the Standard states for the breed but not the ideal, such a dog should be preferred in the evaluation system over one that is not ideal and outside the Standard’s limits.

Judges who are able to estimate heights in this breed accurately never put up a Doberman because it is oversize nor penalize one excessively that is under the ideal but within the height range.

7. In many All Breed magazines there are discussions about the ‘Generic American Show Dog’; the Doberman is often mentioned in these articles. Do oversize Dobermans contribute to this image and if so, are more oversize Dobermans successful because this image is becoming acceptable?

- George Rood

- Magazines do have an effect on the size of the Doberman. Large stud dogs that are big winners are more often bred and contribute to the increase in overall size.

- Dr. Anthony DiNardo

- We live in a time where we have available improved nutrition, which may have some effect on the size of all animals. However, I believe the real problem is the loss of the breeding kennels. In the past, the development of the breed was directed by large kennels (i.e. – Kay Hill, Vom Ahrtal, Marienburg, etc.). These breeders understood the Standard and bred to produce offspring that represented it. For the most part this is gone. Most new breeders know the Doberman Pinscher as it is and not how it was in the past. Therefore, to many, only the Doberman Pinscher of today is what they have to emulate. If the Doberman Pinscher enthusiasts would learn the Standard, accept it without reservation and try to breed to emulate the medium-sized, compact, square-angulated Doberman Pinscher there would be no size problem.

- Bill Garnett