Breeder/Exhibitor Ed, Breeding/Genetics

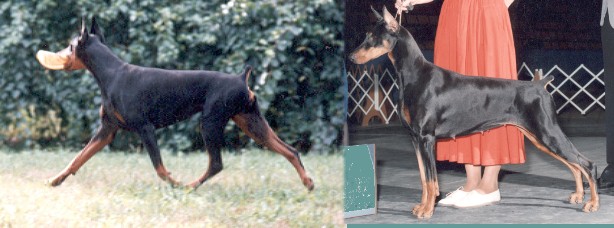

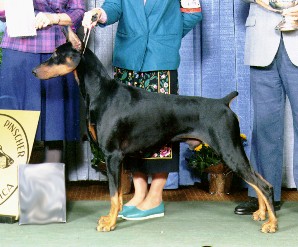

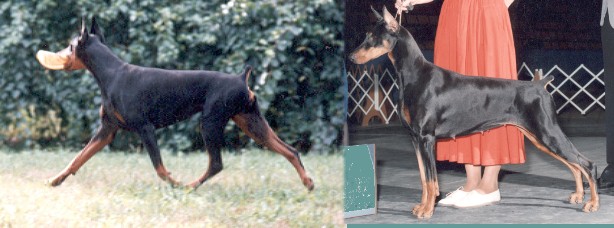

Free, balanced, and vigorous, with good reach in the forequarters and good driving power in the hindquarters. When trotting, there is strong rear-action drive. Each rear leg moves in line with the foreleg on the same side. Rear and front legs are thrown neither in nor out. Back remains strong and firm. When moving at a fast trot, a properly built dog will single-track.

Free, balanced and vigorous, with good reach in the front and good driving power in the rear – in the gait, the standard stresses balance. The dog should give you the same impression when it moves as it does when standing — “standing in motion”. Needless to say, the dog that is straight at both ends will move balanced, but may not be correct. You must consider all factors when a dog moves. How does he carry himself, how does the neck fit into the shoulder, is the topline level, where is the tail placement, how does the dog feel about himself (proud carriage, reflecting great nobility, etc)?

Moving away from and toward the judge, the Doberman’s legs should move toward the center. Dobermans single track at different speeds, so the speed of moment in the ring may not be the one that allows the dog to show you that. If the dog is single tracking at a slow speed, chances are very good that if moved a little faster, the legs will cross. How a dog moves toward a center line may be more important than whether it does! An example of a dog moving “straight” coming and going — the rear leg on the right should be moving in the line with the front leg on the right. Joints should also be observed; the dog should move with efficiency with no extra movement of joints (some examples would be flipping feet or loose elbows).

From the side, a Doberman should not move like a German Shepherd. Reach and drive are moderate. A properly build Doberman does not have an extreme gait. It’s quite popular to move the dog as fast as possible, but movement cannot be evaluated when the dog is going so fast. “Speed Kills!” The dog should move at a moderate speed and move on a loose lead so you can actually see movement. The topline should be firm with no dips or bumps, the tail should be out and not up, the neck should be extended with the head forward just above the shoulder. Ears may or may not be erect.

A completely balanced gait is like 2 pairs of scissors opening and closing. The feet do not cross (overreach, over-stride) in the center, but meet. The hock should extend and not be set or stay bent (sickle hocked). The reach in front should extend as far as the plane of the nose. The drive behind should have the rear legs reaching under the dog and propelling him forward — not the rear legs kicking out and up behind, which is wasted energy and provides little forward motion. The front and rear should be in complete balance.

When observing a Doberman gaiting, keep the picture of the general conformation and appearance in mind. This picture should be the same in motion or standing still.

You should get the same impression of the dog when it’s standing or moving.

A completely balanced gait is like 2 pairs of scissors opening and closing. The feet do not cross (overreach) in the center, but meet. When the dog is gaiting, evaluate the topline, how the neck fits into the shoulder, tailset, and how the dog feels about himself.

You should get the same impression of the dog when it’s standing or moving.

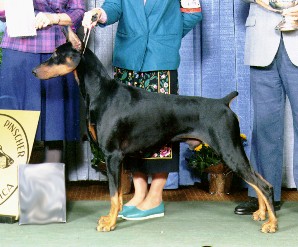

Another illustration of a well balanced, powerful side-gait.

As stated above, evaluate the parts of the dog as he gaits, just as you would when he’s standing.

The Doberman is built to be a double suspension galloper (all feet are off the ground at full extension or full contraction). Flexibility and a strong back are important.

Click the following links to read more articles in the “Dobermans in Detail” series:

Size, proportion &substance

Head

Neck Topline and Body

Forequarters

Hindquarters

Coat

Gait

Temperament

Conclusion: test yourself

by Linka Krukar submitted by Marj Brooks

Breeder/Exhibitor Ed, Breeding/Genetics

Smooth-haired, short, hard, thick and close lying, invisible gray undercoat on neck permissible.

It is specifically stated that the coat is smooth-haired, short, hard thick and close lying. Anything other than what is listed is a deviation. Does the standard address cowlicks? Obviously it does. The coat should look shiny and look healthy. It should not be thin, sparse or brittle.

COLOR AND MARKINGS

Allowed Colors: Black, red, blue, and fawn (Isabella). Markings: Rust, sharply, appearing above each eye and on muzzle, throat and forechest, on all legs and feet, and below tail. White patch on chest, not exceeding ½ square inch, permissible. Disqualifying Fault: Dogs not of an allowed color.

Dobermans come in four allowed colors– black, red (various shades of reddish brown), blue (bluish gray), fawn (beige). Blue is a dilution of black and fawn is a dilution of red. The black Doberman has the most hair per square inch, thus the thickest coat. A fawn has the least hair per square inch, so usually the thinnest coat. Expect the same of all colors in terms of coat and overall quality. Many fawns tend to have lighter color hair on their heads. They should all have dark eyes and good coats, with rust markings. The markings are to be sharply defined — which means clearly distinguishable from the base color of the dog. Sharply defined dark rust markings may be harder to distinguish because of less contrast between the base color and the rust, but should never be faulted! Markings are defined as rust, not tan! White hairs on the chest or a small white patch is permitted up to ½” square, approximately the size of a dime. Thus, the standard states that the white patch is not a deviation unless the size is large than a dime.

Click the following links to read more articles in the “Dobermans in Detail” series:

Size, proportion &substance

Head

Neck Topline and Body

Forequarters

Hindquarters

Coat

Gait

Temperament

Conclusion: test yourself

by Linka Krukar submitted by Marj Brooks

Breeder/Exhibitor Ed, Breeding/Genetics

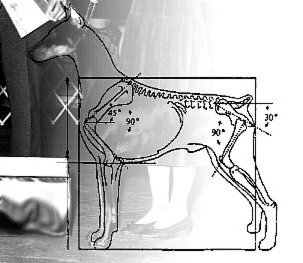

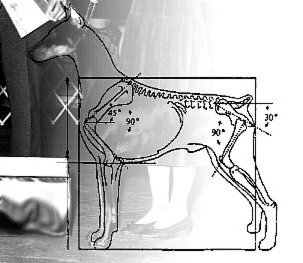

The angulation of the hindquarters balances that of the forequarters. Hip Bone falls away from spinal column at an angle of about 30 degrees, producing a slightly rounded, well filled-out croup. Upper Shanks at right angles to the hip bones, are long, wide, and well muscled on both sides of thigh, with clearly defined stifles. Upper and lower shanks are of equal length. While the dog is at rest, hock to heel is perpendicular to the ground. Viewed from the rear, the legs are straight, parallel to each other, and wide enough apart to fit in with a properly built body. Dewclaws, if any are generally removed. Cat feet as on front legs, turning neither in nor out.

Again the standard is very specific; balance is called for between the front and the rear of the dog. The rear assembly mirrors the front assembly in its requirement for angles and balance, thus it is imperative that the rear is in balance with the front! Do not judge the rear independently from the front! The hip bone falls away from the spinal column at such an angle (30 degrees) to produce the slightly rounded, well filled out croup. When the hip bone appears to follow the line of the back when viewed from the side instead of being angled at 30 degrees, the croup appears flat, with the accompanying high set tail that is INCORRECT! Because handling can distort rears, it is very important to judge the angle of the croup when the dog is in motion or standing on its own. When the dog with the correct angulation moves, he will have a powerful rear that propels him forward without wasted energy of the high kick up behind. When the dog with the flatter croup moves, the tail will be carried too high (remember slightly above the horizontal — out rather than up) and the rear legs will be moving up and behind (in wasted motion) rather than under the dog “digging” into the ground to propel him forward. Right angles are called for between the long, wide, and well muscled upper shanks and hip bones, with clearly defined stifles. There are many straight stifles to go with the straight front assemblies. These straighter stifles are usually accompanied by a long hock. There are also many long stifles that are out of balance with the front, so the dog’s rear legs are too far behind the rear assembly — the dog “stands over a lot of ground” like a German Shepherd. Keep in mind that the standard requires equal length of upper and lower shanks. Because of the specific angles the standard requires, without specifically mentioning the word “hock”, it is clear that it must be short. The shorter the hock, the stronger the joint, thus the long hock is another way of compensating for the less than desired short, straight stifle. This is usually evident when you watch the dog move and the rear “follows the front” instead of providing power to propel the dog forward.

The standard specifically states a “clearly defined stifle”, but does not call for a “well turned stifle”. The reasons for these requirements are partly functional and partly in genetic problems of the breed. In the early mixtures, many Dobermans appeared with longer rear legs than front legs. The judge that “prefers” the longer legged rear with the sweeping turn of stifle may be augmenting the problem! Judge to the standard! Remember when judging the rear — begin with the hip, then proportions, then the degrees of angulation as compared to the front.

|

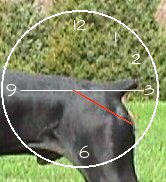

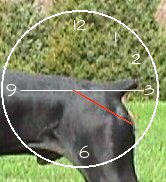

The photo shows correct tail placement (slightly above the horizontal)

The red line shows that the hip bone falls away from the spinal column at a 30 degree angle to produce the slightly rounded, well filled out croup

|

|

Click the following links to read more articles in the “Dobermans in Detail” series:

Size, proportion &substance

Head

Neck Topline and Body

Forequarters

Hindquarters

Coat

Gait

Temperament

Conclusion: test yourself

by Linka Krukar submitted by Marj Brooks

Breeder/Exhibitor Ed, Breeding/Genetics

Shoulder Blade sloping forward and downward at a 45-degree angle to the ground meets the upper arm at an angle of 90 degrees. Length of shoulder blade and upper arm are equal. Height from elbow to withers approximately equals height from ground to elbow. Legs seen from front and side, perfectly straight and parallel to each other from elbow to pastern; muscled and sinewy, with heavy bone. In normal pose and when gaiting, the elbows lie close to the brisket. Pasterns firm and almost perpendicular to the ground. Dewclaws may be removed. Feet well arched, compact, and catlike, turning neither in nor out.

Shoulder blade sloping forward and downward at a 45 degree angle – Although this angulation is impossible to get, it indicates the importance placed on the angulation of the shoulder. This angulation allows for the beautiful, smooth flow of the neck into the shoulder. The Doberman standard repeatedly stresses the balance of all the parts – length of shoulder blade to upper arm are equal; the height from elbow to withers approximately equals height from ground to elbow. Many Dobermans have the entire shoulder assembly pushed forward with a short upper arm. The better the layback of shoulder, the longer and smoother the neck will appear (it should still be in proportion to everything else). Again, the depth of body should be equal to the length of leg. This does NOT allow for the high stationed dog that many find so appealing. Applying the standard takes precedence over personal preference. When the proportions are correct, the dog appears shorter on leg and longer in body. The dog that has more length of leg and less depth of body generally may give the illusion of being square, but in reality, is really too short backed.

The legs are straight, which means they don’t have the curves of the achondroplastic breeds. While the correct pastern appears almost straight, there is a “slight”, although very slight bend in the pastern. A pastern that is too straight or long cannot absorb the impact of gaiting. It is NOT correct!

Heavy bone does not mean big boned, it refers to a round bone versus an oblong bone, which has the appearance of “light” bone. The 1948 standard stated “legs… muscled and sinewy with round, heavy bone”. In normal pose and when gaiting, the elbows lie close to the brisket–look at the dog from the back and you should be able to see the elbow fit tightly into the brisket. There should be no air space between the elbow and body. If you can see through the area or it looks like you can get a hand in there, the lay on is not correct and the dog will probably stand wide, move wide or toe in and not gait properly.

Feet well arched, compact and catlike, turning neither in nor out – a dog with large or flat feet is like a car with flat tires. Well arched feet that are held strongly together indicate tight tendons for good shock absorption. Long toes are associated with longer tendons and usually weaker (or more let down) pasterns. This will be evident when the dog moves. Toes should be short and tight. Large feet will not only have the appearance of sloppy movement, but cannot cushion or absorb as well as the short, tight toes. Judge the “turning neither in nor out” when the dog is moving. Dogs can be trained to stand properly, but they will move naturally.

|

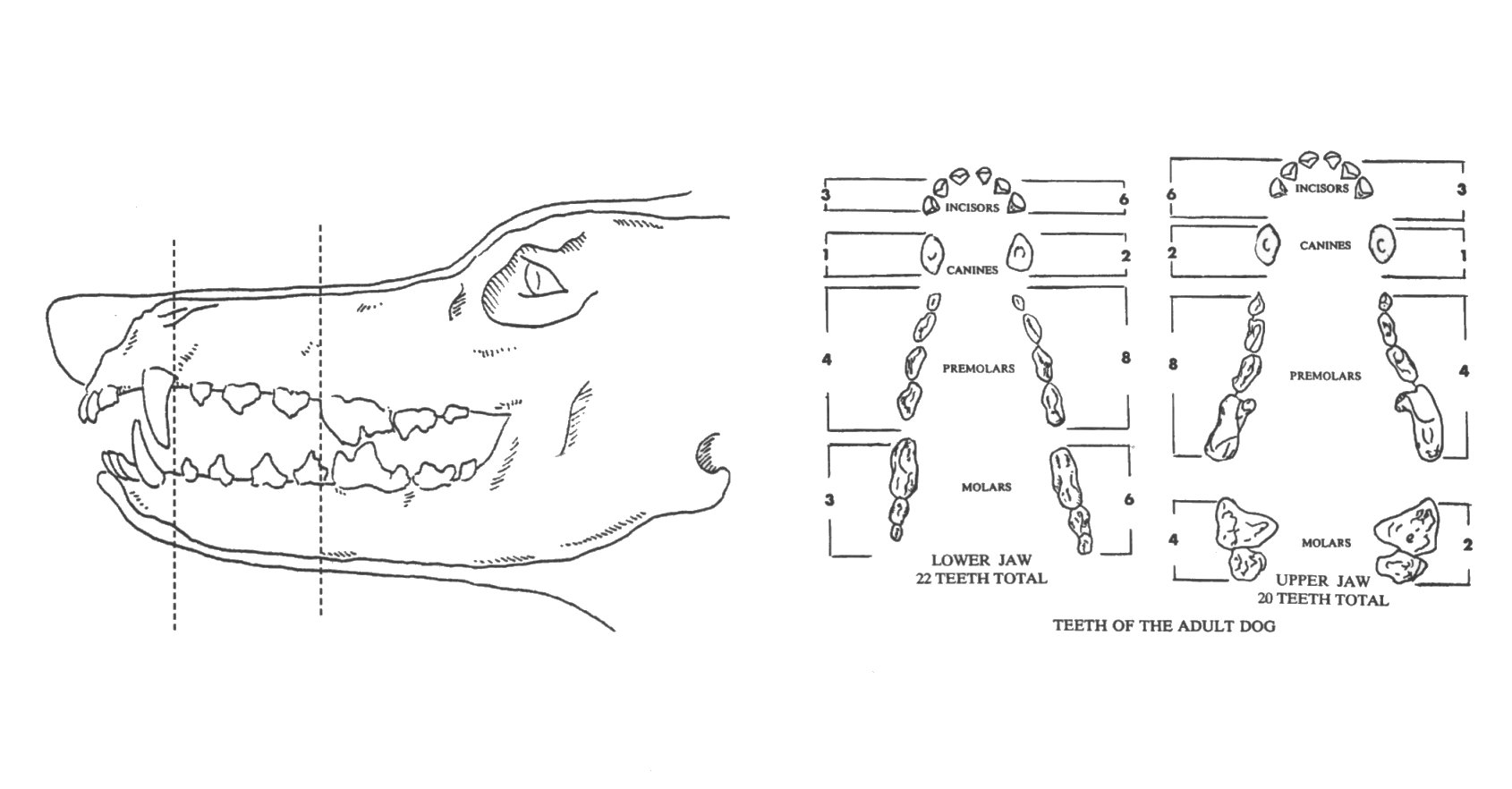

Two examples of cat feet.

|

|

|

|

Left is a young dog and right is an adult

|

Click the following links to read more articles in the “Dobermans in Detail” series:

Size, proportion &substance

Head

Neck Topline and Body

Forequarters

Hindquarters

Coat

Gait

Temperament

Conclusion: test yourself

by Linka Krukar submitted by Marj Brooks

Breeder/Exhibitor Ed, Breeding/Genetics

Neck proudly carried, well muscled and dry. Well arched, with nape of neck widening gradually toward body. Length of neck proportioned to body and head. Withers pronounced and forming the highest point of the body. Back short, firm, of sufficient width, and muscular at the loins, extending in a straight line from withers to the slightly rounded croup.

Chest broad with forechest well defined. Ribs well sprung from the spine, but flattened in lower end to permit elbow clearance. Brisket reaching deep to the elbow. Belly well tucked up, extending in a curved line from the brisket. Loins wide and muscled. Hips broad and in proportion to body, breadth of hips being approximately equal to breadth of body at rib cage and shoulders.

Tail docked at approximately second joint, appears to be a continuation of the spine, and is carried only slightly above the horizontal when the dog is alert.

Neck proudly carried, well muscled and dry – The neck is proportional in length and width to the head and body, tapering gently from the body to the head. It appears almost as wide as the body at the body, tapering gracefully but powerfully to the head. The muscle that runs from behind the ear, down the neck, down the front and attaches itself around the upper arm, helps pull the upper arm forward while the dog is gaiting, thus assisting in the reach of the dog. Again, the length of the neck should be in proportion to the body and head. A short neck reduces reach and a neck that is too long stretches the muscle making it weaker, so the dog has to struggle more for efficient gaiting and balance. The neck should widen gradually toward the body- it should not be “skinny” or “thick” and have a natural arch (not the one the handler molds into the dog). The withers form the highest point of the body. All measurements are proportional to the height at the withers; all parts are in proportion to the body.

Back is short, firm – If the back is too short, the dog is out of balance and can’t move out of it’s own way, and usually compensates by over-striding or over-reaching. These dogs compensate in several ways; some may have longer, more sweeping stifles like a German Shepherd or Weimaraner, and some may have straighter stifles with long hocks. If the back is too long, the entire topline can sag or bounce when the dog moves. The problem with the requirement of a square body with a short back, plus the additional 90 degree angulation at each end of the dog, is that there is no way the dog can get out of it’s own way unless it’s in complete balance!

Back of sufficient width, and muscular at the loins, extending in a straight line from withers to the slightly rounded croup– when looking down on the dog, there should be an “hour glass” shape and not a “tube”. The shoulders, ribs, and the rear should be the same width. The slightly rounded croup may not look as pleasing as the flat croup, but it is correct. In this case the “back” is referring to the topline and should be in a straight line from the withers to the correct croup. This straight line is based on a correctly built dog and will be `level’ rather than `sloping’ if the dog has correct structure. The dramatically sloping topline is a clear indication that proper balance is not present because the angles at each end don’t match. The dog with a level to slightly sloping topline has correct balance. The correct topline fits a dog whose legs are under him, ready to move in any direction. The dog’s major weight is balanced on his front feet, rear legs squarely set, ready to move forward or to the side. The extremely sloping topline fits a dog standing, but not ready for movement. The topline will slope if the shoulders are straighter or if the dog has too much turn of stifle, which will lower the rear.

Chest is broad with the forechest well defined – meaning that the forechest has “definite and distinct lines or features,” not necessarily well endowed! The original 1923 standard stated “chest arched and reaching deep to the elbow.” Moderation is another key to a Doberman. A Doberman is not supposed to have excessive forechest, but enough to indicates there is a forechest; showing the precise outline of it. A large forechest doesn’t necessarily mean a good front.

Brisket reaching deep to the elbow – The depth is important because a larger body cavity allows more room for the organs. The underline is formed by the 1) deep brisket which flows back through 2) the ribs that extend far back in the body that gradually shorten to form 3) the tuck up flowing into the short loin. These are all important to a correct body and the impression of power and endurance. Underlines can have as many problems as toplines! Belly well tucked up does not mean a wasp waist or herring gut. The tuck up can be too extreme or the reverse of no, or too little tuck up giving the dog a `flat’ underline that appears straight across. The underline should gradually angle up to allow the hindquarters to reach under the dog comfortably while the dog is gaiting.

Loins wide and muscled, but not as wide as the rear. The rear should not be narrow, but broad and well muscled, it should be the same width as the ribs- assuming the dog is not slab sided.

Tail docked at approximately the 2nd joint, appears to be a continuation of the spine and is carried only slightly above the horizontal when the dog is alert – tail length varies from one to three joints. One joint appears very short, while three can be quite long. The correct tail appears to be a continuation of the spine and is carried just above horizontal (when the dog is alert). The tail carriage is out, rather than up. Thus if you were looking at a clock, 3 o’clock is obviously horizontal, the correct tail placement is around 2 o’clock, much lower carriage than usually seen. A higher tail does not look like a continuation of the spine and generally indicates a flat, rather than slightly rounded croup. This may be pleasing to the eye, but it INCORRECT structure! If you had the same degree of `incorrectness’ in the front, it would be like saying you like a straight shoulder — that a straight shoulder is pleasing!

Tail carriage (slightly above the horizontal when the dog is alert) (3 o’clock is horizontal)

|

At 2 o’clock

|

At 1 o’clock

|

At 12 o’clock

|

|

|

|

|

Click the following links to read more articles in the “Dobermans in Detail” series:

Size, proportion &substance

Head

Neck Topline and Body

Forequarters

Hindquarters

Coat

Gait

Temperament

Conclusion: test yourself

by Linka Krukar submitted by Marj Brooks

Breeder/Exhibitor Ed, Breeding/Genetics

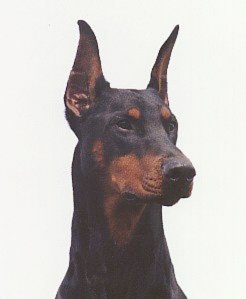

Long and dry, resembling a blunt wedge in both frontal and profile views. When seen from the front, the head widens gradually toward the base of the ears in a practically unbroken line. Eyes almond shaped, moderately deep set, with vigorous, energetic expression. Iris, of uniform color, ranging from medium to darkest brown in black dogs; in reds, blues, and fawns the color of the iris blends with that of the markings, the darkest shade being preferable in every case. Ears normally cropped and carried erect. The upper attachment of the ear when held erect, is on a level with the top of the skull. Top of skull flat, turning with slight stop to bridge of muzzle, with muzzle line extending parallel to top line of skull. Cheeks flat and muscular. Nose solid black on black dogs, dark brown on red ones, dark gray on blue ones, dark tan on fawns. Lips lying close to the jaws. Jaws full and powerful, well filled under the eyes.

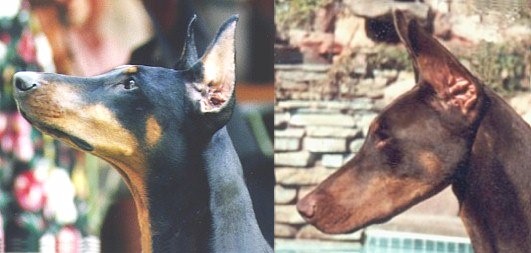

When judging the head, examination requires three views.

- Full front looking down on the head

- Full profile

- A ½ front view to assess the proportion of the head to the body.

Long and dry, resembling a blunt wedge in both frontal and profile views. When seen from the front, the head widens gradually toward the base of the ears in practically an unbroken line – the muzzle and top of the head appear to be the same length (ratio of 1:1). Jaws full and powerful, well filled under the eyes, which means when you put your hands on the side of the muzzle, there should be a “face” filling your hands. If not, the dog doesn’t have enough “fill” under the eyes. Fill under the eye is important for a correct head because the jaws must be full and powerful to hold the 42 strongly developed and correctly placed teeth.

From the side you should have the same impression of the head as from the front. This means the dog should have some underjaw, not just a chin with a lip over it to give the impression of a blunt wedge. Good underjaw can be seen from the front and profile view. The side view will show the flat skull with the line of the skull parallel to the line of the muzzle. The stop is `slight’, thus the ideal amount is more than a Collie and less than a Great Dane.

The head should be correctly proportioned for the body. The Doberman is not a “head” breed, so the basic question is whether the head fits the individual dog. That’s why it’s important to observe the head from different views.

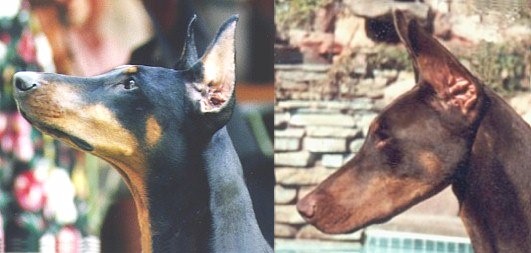

|

|

|

Good underjaw can be seen from the profile view

|

Eyes almond shaped and moderately deep set, with vigorous, energetic expression – Round eyes give the dog a softer expression as does a shallower set eye. Eyes are moderately deep set, which means “middle” – not too deep and not too shallow. Because of the original purpose of the breed, a dark eye is much more desired. Black dogs with yellow/gold eyes, red dogs with green or yellow eyes, blue dogs with gold or gray eyes and fawns with blue or gold eyes are not desired, darker eyes are preferred. The standard states medium to dark brown eyes on a black dog, so are black eyes a deviation of the standard? If you notice any prominence to the eyes (color, shape, depth), it is most likely a deviation.

Ears normally cropped and carried erect – The original 1923 standard stated that ears were “well placed and clipped to a point”. Today’s standard is telling us that ears are either “usually cropped” or “cropped in a normal fashion”. What is a normal ear crop and should we now base our opinion of the dog’s ears on what someone has unnaturally done to our dogs? Obviously where the ears are placed on the head is more important than the crop. A bad ear crop can pull an ear down so they wing out, literally pull an ear down so it won’t stand erect, or distort the shape of the head altogether. Most ears are cropped very long and it’s difficult for the dogs to keep them up. Do NOT expect a dog to carry ears erect while gaiting, unless they are alert to something as they are moving. An exceptionally short crop can give the appearance of a shorter neck, shorter and wider muzzle. Since the standard states that ears are “normally” cropped, is an uncropped ear is a deviation of the standard? Rather than harshly penalize a dog with uncropped ears, determine if the ears are in proportion to the head and the placement is correct.

|

A short ear crop

|

A long ear crop

(what is usually seen)

|

Uncropped

|

|

|

|

|

Judge the dog on the ear placement and carriage, not the (man made) crop or lack there of. The dog on the left and middle are the same dog. The natural eared dog has a cowlick. A short ear crop or natural (uncropped) ear can give the illusion of a wider head, shorter muzzle and shorter neck.

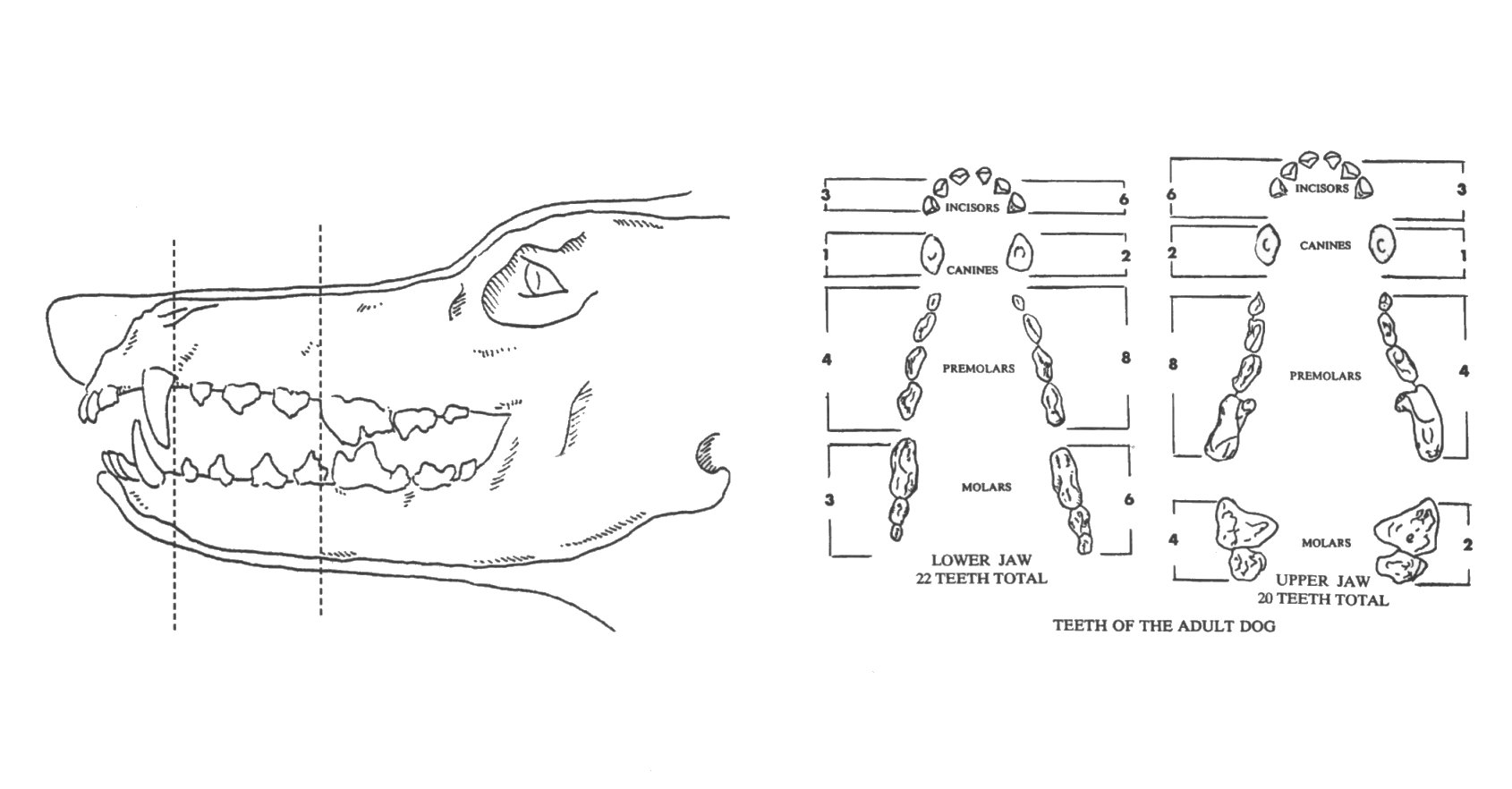

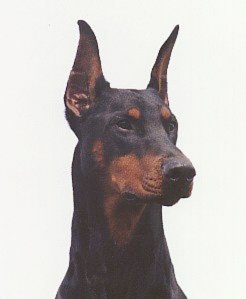

Teeth strongly developed and white. Lower incisors upright and touching inside of upper incisors- a true scissors bite. 42 correctly placed teeth, 22 in the lower, 20 in the upper jaw. Distemper teeth shall not be penalized. Disqualifying Faults: Overshot more than 3/16 of an inch. Undershot more than 1/8 of an inch. Four or more missing teeth.

Teeth strongly developed and white. Lower incisors upright and touching inside of upper incisors – a true scissors bite. 42 correctly placed teeth, 22 in the lower, 20 in the upper jaw. Distemper teeth shall not be penalized. Disqualifying Faults: Overshot more than 3/16 of an inch. Undershot more than 1/8 of an inch. Four or more missing teeth.

There is a purpose for such emphasis on this strong head – to hold the strongly developed (good size

d) teeth. Since three of the four disqualifications are in the mouth, it is important know what a correct mouth looks like and be accurate when counting teeth. The standard assumes that you know the names of all the teeth. Correctly placed teeth lets you know that a missing tooth replaced by an extra tooth is a deviation from the standard and must be considered as a fault. You may have 42 correctly placed teeth, and extra teeth in the spaces – consider this as a deviation from the required “correctly placed” teeth. It is not the same as missing teeth, which lead to a disqualification, but a deviation and should be considered to the extent that they affect occlusion and the number of extra teeth. To say that a dog with 3 extra teeth is the same as having a dog with 3 missing teeth is incorrect. The standard is clear that 4 missing teeth is a disqualification, it does NOT state that 4 extra teeth is a disqualification; but a deviation.

The three disqualifications in the mouth — the requirement of a true scissors bite– overshot more than 3/16″ and undershot more than 1/8″ make up two disqualifications. The standard is clearly stating what a scissors bite is. No, we have no tool to measure the exact distance that makes up the over or undershot bite, but the standard is clear as to how far over or undershot we should tolerate – how close the `scissors’ should be. Without these `measures’ a “true scissors” bite is left to interpretation. Four or more missing teeth is the third disqualification in the mouth, so it is important to know how to count teeth and identify them.

|

The only way to check for missing teeth is to OPEN THE MOUTH.

|

|

A quick lesson in counting teeth:

The standard specifies the number of teeth, the correct placing of the teeth and by implication, occlusion, so be sure to check for all of these. The easiest way is to count teeth is in groups. On the top there are two groups of 3 and 3 (two groups of three teeth on each side) and in the lower jaw two groups of 4 and 3. The only way to check for missing teeth is to OPEN THE MOUTH. There is no way to determine if the back molars are present with the mouth closed. Overshot and undershot are deviations from the scissors bite. They are to be considered a fault the same as missing teeth. While a level bite is not correct, it is only a deviation from what is correct, and should be considered just as any other deviation, over faults that may be more important to the overall dog. Occlusion should be checked from the side as well as the front of the mouth. The only way to check for missing teeth is to OPEN THE MOUTH.

Click the following links to read more articles in the “Dobermans in Detail” series:

Size, proportion &substance

Head

Neck Topline and Body

Forequarters

Hindquarters

Coat

Gait

Temperament

Conclusion: test yourself

by Linka Krukar submitted by Marj Brooks

Breeder/Exhibitor Ed, Breeding/Genetics

Height at withers: Dogs 26 to 28 inches, ideal about 27 ½ inches; Bitches 24 to 26 inches, ideal about 25 ½ inches. The height, measured vertically from the ground to the highest point of the withers, equaling the length measured horizontally from the forechest to the rear projection on the upper thigh. Length of head, neck and legs in proportion to length and depth of body.

The Doberman is medium sized, with total balance of height to length. Correct size is one of the most important factors in maintaining breed type. Medium size refers to the combination of height and bulk. Height at the withers: Dogs 26-28″, Bitches 24-26″– It would be rare to see an adult dog or bitch in the conformation ring that is too small for the standard. The ideal 27 ½” male or 25 ½” bitch is usually one of the smaller dogs in the ring today. Today many bitches are over 26″ and dogs well over 28″. This is NOT correct!!! As an aside, on two occasions the DPCA membership voted to disqualify dogs one inch over the standard. While this has never been added to the standard, it does stress the importance that is placed on the correct height to remain a medium sized breed. Years ago a letter was sent to judges stressing the importance of the correct height.

When measuring the Doberman, measure height from the highest point of the wither (not the shoulder blade) to the ground . Measure length from the forechest to the rear projection of the upper thigh. Know where those parts are and know what correct size looks like. A longer neck may give the dog the appearance of being taller than he is. The length of head, the neck and the legs are in proportion to length and depth of body- all the parts fit together. No one part stands out, they all flow together to make one picture.

If any part stands out, whether exceptionally good or bad, it will be distracting from the total picture. The height and length are equal, and the depth of body is equal to the length of leg. Just as the height/length was measured as equal, now the measurement of the wither to the elbow and then elbow to the ground should be the same. When these proportions are equal, a square dog generally appears too long, and/or too short on leg. Based on the description, a dog in perfect balance will also have a head the same length as the length of the neck.

Click the following links to read more articles in the “Dobermans in Detail” series:

Size, proportion &substance

Head

Neck Topline and Body

Forequarters

Hindquarters

Coat

Gait

Temperament

Conclusion: test yourself

by Linka Krukar submitted by Marj Brooks

Breeder/Exhibitor Ed, Breeding/Genetics

The Doberman Pinscher standard is probably one of the most precise and clearly written standards around today. It leaves very little out, and clearly states that any deviation from it’s description is penalized to the extent of that deviation. If it is NOT stated in the standard, it IS a deviation- that’s very clear! To understand Doberman structure, it’s important to know it’s original purpose. The Doberman was originally bred for its character, but designed to be geometrically and esthetically perfect. It began with what they wanted the dog to do– watchdog, guard dog, fearless, a short backed galloper, agile, fast, powerful and sturdy; to mention just a few things. Features for beauty were “built in” to the mathematical outline.

The standard, from beginning to end, demands an orderly and harmonious arrangement of parts to create a statically and kinetically balanced dog. Thus whether the dog is standing or moving, the parts must be in total harmony. The impression of the dog should be the same, whether the dog is in motion or stationary. The key to the Doberman is balance and proportion. All the parts fit into the other parts smoothly with no distractions. If any part stands out, whether good or bad, it takes away from the total picture and the balance and proportion is disrupted. As you go through the standard, you will see just how specific the description of the Doberman Pinscher is. Some points are so important, they are referred to in more than one section of the standard. To ignore the standard is an injustice to the breed and will change the Doberman forever.

GENERAL CONFORMATION AND APPEARANCE

The appearance is that of a dog that is of medium size, with a body that is square. Compactly built, muscular and powerful, for great endurance and speed. Elegant in appearance, of proud carriage, reflecting great nobility and temperament. Energetic, watchful, determined, alert, fearless, loyal and obedient.

This is the single most important paragraph in the standard.

In evaluating the Doberman, the first directive under general conformation and appearance is a dog of medium size (which is specified in more detail later in the standard). The reference to size includes a combination of height, bone, and substance (or bulk). The ideal bone and substance needed for correct balance is always in relation to a dog’s height. The taller dog requires more bone and substance for correct balance than a dog at the lower height limit of the standard. Since there is a diversity in the top and bottom limits of height, the dog must be considered as an individual and not compared to others when evaluating this. Height can be deceiving depending upon the amount of bone and/or substance a dog has. Size is a fundamental breed characteristic so it is very important that the Doberman has the appearance of a medium sized dog. The standard requires a combination of endurance and speed that could only be achieved in a medium sized dog. Size is very important! A medium sized Doberman is more agile and has good endurance, but still has enough size to generate the power needed to function successfully as a working dog. A dog larger than the specified proportions is approaching a giant breed, not a Doberman!

In the very beginning and throughout the standard, balance (or proportion) is probably stressed more than any other single point. By stating that the body is square, we have the first reference to balance- a dog of balanced proportions, balance being essential to soundness. Square means that the dog’s body is in horizontal and vertical balance, which also means the angles at both ends must match. Keep in mind that the standard states that it is the BODY that appears square, not the entire outline of the dog! In fact, a dog that looks square is probably too short!! Angles affect the appearance of square, with the straight, upright dog appearing more square than the dog of the same proportions with more angulation, who will appear longer in length.

Compactly built indicates that the dog should have a short, solid physique. Muscular and powerful indicates that the dog is in good condition with hard muscle, thus capable of performing effectively. The Doberman is an athlete. To have speed also, the dog must be in correction proportion of bone to substance and not so heavily boned or muscular so as to become too cumbersome. Thus the other extreme of fine boned or spindly is equally unacceptable.

Elegant in appearance, of proud carriage, reflecting great nobility and temperament-

Elegant does not mean fine boned, weak or delicate. The dog should look “poured” into it’s skeleton, all one piece. The naturally arched neck flows into smooth shoulders which continue to the strong, level topline, with no lumps, bumps or dips; continuing on to the tail, which appears to be a continuation of the spine. The coat is short, hard, shiny, and fits so smoothly over the body that the dog looks poured into it. Elegance is tasteful beauty of manner, form or style. Some other words for elegant are aristocratic, balanced, beautiful, dignified, graceful, harmonious, sleek, stately, stylish. To achieve this look, the dog must also be able to stand regally on its own without the benefit of being molded by its handler.

Proud carriagereflects how the dog feels about himself, indicating a high opinion of himself, a feeling of confidence, a spirited manner; all which relate to temperament. A dog that exudes confidence will naturally have a proud carriage and should have a sound, steady temperament.

Energetic means possessing, exerting or displaying vitality and intensity of expression; lively, powerful, and spirited. This breed characteristic is often displayed by a dog that appears to be filled with controlled energy. A dog that hangs its head, is listless or plods along behind the handler is not displaying much `energy’.

Watchful means vigilant, closely observant, being alert and aware of the surroundings and reacting to them. The dog shouldn’t be wary or cautious unless the situation calls for these reactions. A dog that remains aware of the judge’s approach by moving his head to glance at the judge or flicking the ears after the examination is being watchful. The dog that only responds to bait is not demonstrating this characteristic. Some dogs take a little longer to focus on bait when asked to freebait after gaiting because they may be more aware of what’s going on around them than the immediate interest in bait.

Determinedincludes firmness of purpose, resolve, and fixed intention. An example of this could be the dog that takes notice of something on the ground while gaiting and the next time around takes the opportunity to get a closer look (or taste). The dog may refuse to face a certain direction

or refuse to walk in a certain area. It is a strong- minded breed.

Alert refers to being vigilantly attentive, aware, mentally responsive and perceptive, quick. To be alert, the dog should be ready to react to anything they consider unusual. It doesn’t mean staring at bait, ignoring what goes on around him. In this case, staring at bait may be trained!

Fearless, the absence of fear, also includes brave, courageous (which implies consciously rising to a specific test by drawing on a reserve of inner strength), intrepid (invulnerability to fear), and bold (which stresses not only the readiness to meet danger or difficulty, but often also a tendency to seek it out). The fearless dog’s reaction to something new or unusual is to stand ready. The judge should be able to approach the dog when standing on a loose leash.

Loyal refers to being faithful to a person or duty. This trait may not be possible to evaluate in the show ring, but is demonstrated to the person who cares for the dog.

Obedience is demonstrated in the dog’s behavior and response to the person handling the dog, the judge, and his surroundings. While some of these qualities are not immediately evident in the conformation ring, they are observed in varying degrees depending on the situation. Dobermans should not be robots, paying attention to only the bait, standing perfectly like a statue. They should respond to everything going on around them which does include the bait, other dogs, people, sounds, etc.

Assessing temperament begins with `reading’ the dog’s eyes. Look for an interested, confident, curious dog, that is ready for anything and sure that he can handle anything that comes his way. The characteristics of behavior are very important to the total picture of the Doberman, just as the physical attributes that follow are.

As previously stated, the statements in this section make up the single most important paragraph in the standard- if you remember what it is telling you about the breed, the other parts of the standard fall into place.

|

|

|

|

Outline of dog

|

Outline of bitch

|

Click the following links to read more articles in the “Dobermans in Detail” series:

Size, proportion &substance

Head

Neck Topline and Body

Forequarters

Hindquarters

Coat

Gait

Temperament

Conclusion: test yourself

by Linka Krukar submitted by Marj Brooks

Breeder/Exhibitor Ed, Breeding/Genetics

|

Surprising as it may seem, it isn’t capacity that explains the differences that exist between individuals because most seem to have far more capacity than they will ever use. The differences that exist between individuals seem to be related to something else. The ones who achieve and out perform others seem to have within themselves the ability to use hidden resources. In other words, it’s what they are able to do with what they have that makes the difference.

In many animal-breeding programs the entire process of selection and management is founded on the belief that performance is inherited. Attempts to analyze the genetics of performance in a systematic way have involved some distinguished names such as Charles Darwin and Francis Galton. But it has only been in recent decades that good estimates of heritability of performance have been based on adequate data. Cunningham (1991) in his study of horses found that only by using Timeform data, and measuring groups of half brothers and half sisters could good estimates of performance be determined. His data shows that performance for speed is about 35% heritable. In other words only about 35% of all the variation that is observed in track performance is controlled by heritable factors, the remaining 65% are attributable to other influences, such as training, management and nutrition. Cunningham’s work while limited to horses provides a good basis for understanding how much breeders can attribute to the genetics and the pedigrees.

Researchers have studied this phenomena and have looked for new ways to stimulate individuals in order to improve their natural abilities. Some of the methods discovered have produced life long lasting effects. Today, many of the differences between individuals can now be explained by the use of early stimulation methods.

|

|

|

Introduction

|

|

Man for centuries has tried various methods to improve performance. Some of the methods have stood the test of time, others have not. Those who first conducted research on this topic believed that the period of early age was a most important time for stimulation because of its rapid growth and development. Today, we know that early life is a time when the physical immaturity of an organism is susceptible and responsive to a restricted but important class of stimuli. Because of its importance many studies have focused their efforts on the first few months of life.

Newborn pups are uniquely different than adults in several respects. When born their eyes are closed and their digestive system has a limited capacity requiring periodic stimulation by their dam who routinely licks them in order to promote digestion. At this age they are only able to smell, suck, and crawl. Body temperature is maintained by snuggling close to their mother or by crawling into piles with other littermates. During these first few weeks of immobility researchers noted that these immature and under-developed canines are sensitive to a restricted class of stimuli which includes thermal, and tactile stimulation, motion and locomotion.

Other mammals such as mice and rats are also born with limitations and they also have been found to demonstrate a similar sensitivity to the effects of early stimulation. Studies show that removing them from their nest for three minutes each day during the first five to ten days of life causes body temperatures to fall below normal. This mild form of stress is sufficient to stimulate hormonal, adrenal and pituitary systems. When tested later as adults, these same animals were better able to withstand stress than littermates who were not exposed to the same early stress exercises. As adults, they responded to stress in “a graded” fashion, while their non-stressed littermates responded in an “all or nothing way.”

Data involving laboratory mice and rats also shows that stress in small amounts can produce adults who respond maximally. On the other hand, the results gathered from non-stressed littermate show that they become easily exhausted and would near death if exposed to intense prolonged stress. When tied down so they were unable to move for twenty-four hours, rats developed severe stomach ulcers, but litter mates exposed to early stress handling were found to be more resistant to stress tests and did not show evidence of ulcers. A secondary affect was also noticed.

Sexual maturity was attained sooner in the littermates given early stress exercises. When tested for differences in health and disease, the stressed animals were found to be more resistant to certain forms of cancer and infectious diseases and could withstand terminal starvation and exposure to cold for longer periods than their non-stressed littermates. Other studies involving early stimulation exercises have been successfully performed on both cats and dogs. In these studies, the Electrical Encephalogram (EEG) was found to be ideal for measuring the electrical activity in the brain because of its extreme sensitivity to changes in excitement, emotional stress, muscle tension, changes in oxygen and breathing. EEG measures show that pups and kittens when given early stimulation exercises mature at faster rates and perform better in certain problem solving tests than non-stimulated mates. In the higher level animals the effect of early stimulation exercises have also been studied. The use of surrogate mothers and familiar objects were tested by both of the Kelloggs’ and Dr. Yearkes using young chimpanzees. Their pioneer research shows that the more primates were deprived of stimulation and interaction during early development, the less able they were to cope, adjust and later adapt to situations as adults.

While experiments have not yet produced specific information about the optimal amounts of stress needed to make young animals psychologically or physiologically superior, researches agree that stress has value. What also is known is that a certain amount of stress for one may be too intense for another, and that too much stress can retard development. The results show that early stimulation exercises can have positive results but must be used with caution. In other words, too much stress can cause pathological adversities rather than physical or psychological superiority. |

|

Methods of Stimulation

|

|

The U.S. Military in their canine program developed a method that still serves as a guide to what works. In an effort to improve the performance of dogs used for military purposes, a program called “Bio Sensor” was developed. Later, it became known to the public as the “Super Dog” Program. Based on years of research, the military learned that early neurological stimulation exercises could have important and lasting effects. Their studies confirmed that there are specific time periods early in life when neurological stimulation has optimum results. The first period involves a window of time that begins at the third day of life and lasts until the sixteenth day. It is believed that because this i

nterval of time is a period of rapid neurological growth and development, and therefore is of great importance to the individual.

The “Bio Sensor” program was also concerned with early neurological stimulation in order to give the dog a superior advantage. Its development utilized six exercises which were designed to stimulate the neurological system. Each workout involved handling puppies once each day. The workouts required handling them one at a time while performing a series of five exercises. Listed in order of preference the handler starts with one pup and stimulates it using each of the five exercises. The handler completes the series from beginning to end before starting with the next pup. The handling of each pup once per day involves the following exercises:

- Tactical stimulation (between toes)

- Head held erect

- Head pointed down

- Supine position

- Thermal stimulation

|

1. Tactile stimulation

Holding the pup in one hand, the handler gently stimulates (tickles) the pup between the toes on any one foot using a Q-tip. It is not necessary to see that the pup is feeling the tickle. Time of stimulation 3 – 5 seconds.

(Figure 1)

|

Figure 1 |

-

- Figure 2

|

2. Head held erect

Using both hands, the pup is held perpendicular to the ground, (straight up), so that its head is directly above its tail. This is an upwards position. Time of stimulation 3 – 5 seconds (Figure 2).

|

|

3. Head pointed down

Holding the pup firmly with both hands the head is reversed and is pointed downward so that it is pointing towards the ground. Time of stimulation 3 – 5 seconds (Figure 3).

|

Figure 3 |

Figure 4 |

4. Supine position

Hold the pup so that its back is resting in the palm of both hands with its muzzle facing the ceiling. The pup while on its back is allowed to sleep struggle. Time of stimulation 3-5 seconds. (Figure 4)

|

|

5. Thermal stimulation

Use a damp towel that has been cooled in a refrigerator for at least five minutes. Place the pup on the towel, feet down. Do not restrain it from moving. Time of stimulation 3-5 seconds. (Figure 5)

|

-

- Figure 5

|

|

|

These five exercises will produce neurological stimulations, none of which naturally occur during this early period of life. Experience shows that sometimes pups will resist these exercises, others will appear unconcerned. In either case a caution is offered to those who plan to use them. Do not repeat them more than once per day and do not extend the time beyond that recommended for each exercise. Over stimulation of the neurological system can have adverse and detrimental results. These exercises impact the neurological system by kicking it into action earlier than would be normally expected. The result being an increased capacity that later will help to make the difference in its performance. Those who play with their pups and routinely handle them should continue to do so because the neurological exercises are not substitutions for routine handling, play socialization or bonding. |

| Benefits of Stimulation |

|

Five benefits have been observed in canines that were exposed to the Bio Sensor stimulation exercises. The benefits noted were:

Improved cardio vascular performance (heart rate) Stronger heart beats Stronger adrenal glands More tolerance to stress and Greater resistance to disease.

In tests of learning, stimulated pups were found to be more active and were more exploratory than their non- stimulated littermates over which they were dominant in competitive situations.

Secondary effects were also noted regarding test performance. In simple problem solving tests using detours in a maze, the non-stimulated pups became extremely aroused, whined a great deal, and made many errors. Their stimulated littermates were less disturbed or upset by test conditions and when comparisons were made, the stimulated littermates were more calm in the test environment, made fewer errors and gave only an occasional distress when stressed.

|

| Socialization |

|

As each animal grows and develops three kinds of stimulation have been identified that impact and influence how it will develop and be shaped as an individual. The first stage is called early neurological stimulation, and the second stage is called socialization. The first two (early neurological stimulation and socialization) have in common a window of limited time. When Lorenz, (1935) first wrote about the importance of the stimulation process he wrote about imprinting during early life and its influence on the later development of the individual. He states that it was different from conditioning in that it occurred early in

life and took place very rapidly producing results which seemed to be permanent. One of the first and perhaps the most noted research efforts involving the larger animals was achieved by Kellogg & Kellogg (1933). As a student of Dr. Kellogg’s I found him and his wife to have an uncanny interest in children and young animals and the changes and the differences that occurred during early development. Their history making study involved raising their own new born child with a new born primate. Both infants were raised together as if they were twins. This study like others that would follow attempted to demonstrate that among the mammals there are great differences in their speed of physical and mental development. Some are born relatively mature and quickly capable of motion and locomotion, while others are very immature, immobile and slow to develop. For example, the Rhesus monkey shows rapid and precocious development at birth, while the chimpanzee and the other “great apes” take much longer. Last and slowest is the human infant.

One of the earliest efforts to investigate and look for the existence of socialization in canines was undertaken by Scott-Fuller (1965). In their early studies they were able to demonstrate that the basic technique for testing the existence of socialization was to show how readily adult animals would foster young animals, or accept one from another species. They observed that with the higher level animals it is easiest done by hand rearing. When the foster animal transfers its social relationships to the new species, researchers conclude that socialization has taken place. Most researchers agree that among all species, a lack of adequate socialization generally results in unacceptable behavior and often times produces undesirable aggression, excessiveness, fearfulness, sexual inadequacy, and indifference toward partners.

Socialization studies confirm that the critical periods for humans (infant) to be stimulated are generally between three weeks and twelve months of age. For canines the period is shorter, between the fourth and sixteenth week of age. During these critical time periods two things can go wrong. First, insufficient social contact can interfere with proper emotional development which can adversely affected the development of the human bond. The lack of adequate social stimulation, such as handling, mothering and contact with others, adversely affects social and psychological development.

Second, over mothering can prevent sufficient exposure to other individuals, and situations that have an important influence on growth and development. The literature shows that humans and animals respond in similar ways when denied minimal amounts of stimulation. In humans, the absence of love and cuddling increases the risk of an aloof, distant, asocial or sociopathic individual. Over mothering can also have its detrimental effects. It occurs when a patient insulates the child from outside contacts, or keeps the apron strings tight, thus limiting opportunities to explore and interact. In the end, over mothering generally produces a dependent, socially maladjusted and sometimes emotionally disturbed individual.

The absence of outside social interactions for both children and pups usually results in a lack of adequate learning and social adjustment. Protected youngsters who grow up in an insulated environment often times become sickly, despondent, lacking in flexibility and unable to make simple social adjustments. Generally, they are unable to function productively or to interact successfully then they become adults.

Owners who have busy life styles with long and tiring work and social schedules often times cause pets to be neglected. Left to themselves with only an occasional trip out of the house or off of the property they seldom see other canines or strangers and generally suffer from poor stimulation and socialization. For many, the side effects of loneliness and boredom set-in. The resulting behavior manifests itself in the form of chewing, digging, and hard to control behavior (Battaglia).

It seems clear that small amounts of stress followed by early socialization can produce beneficial results. The danger seems to be in not knowing where the thresholds are for over and under stimulation. Many improperly socialized youngsters develop into older individuals unprepared for adult life, unable to cope with its challenges, and interactions. Attempts to re-socialize them when adults have only produced small gains. These failures confirm the notion that the window of time open for early neurological and social stimulation only comes once. After it passes, little or nothing can be done to overcome the negative effects of too much or too little stimulation.

The third and final stage in the process of growth and development is called enrichment. Unlike the first two stages it has no time limit and by comparison covers a very long period of time. Enrichment is a term which has come to mean the positive sum of experiences, which have a cumulative effect upon the individual. Enrichment experiences typically involve exposure to a wide variety of interesting, novel, and exciting experiences with regular opportunities to freely investigate, manipulate, and interact with them. When measured in later life, the results show that those reared in an enriched environment tend to be more inquisitive and are more able to perform difficult tasks. The educational TV program called Sesame Street is perhaps the best known example of a children’s enrichment program. The results show that when tested, children who regularly watched this program performed better than playmates who did not. Follow up studies show that those who regularly watched Sesame tend to seek a college education and when enrolled, performed better than playmates who were not regular watchers of the Sesame Street Program.

There are numerous children studies that show the benefits of enrichment techniques and programs. Most focus on improving self-esteem and self-talk. Follow up studies show that the enriched Sesame Street students when later tested were brighter and scored above average and most often were found to be the products of environments that contributed to their superior test scores. On the other hand, those whose test scores were generally below average, (labeled as dull) and the products of underprivileged or non- enriched environments often times had little or only small amounts of stimulation during early childhood and only minimal amounts of enrichment during their developmental and formative years. Many were characterized as children who grew up with little interaction with others, poor parenting, few toys, no books and a steady diet of TV soap operas.

A similar analogy can be found among canines. All the time they are growing they are learning because their nervous systems are developing and storing information that may be of inestimable use at a later date. Studies by Scott and Fuller confirm that non-enriched pups when given free choice preferred to stay in their kennels. Other litter mates who were given only small amounts of outside stimulation between five and eight weeks of age were found to be very inquisitive and very active. When kennel doors were left open, the enriched pups would come bounding out while littermates who were not exposed to enrichment would remain behind. The non-stimulated pups would typically be fearful of unfamiliar objects and generally preferred to withdraw rather than investigate. Even well bred pups of superior pedigrees would not explore or le

ave their kennels and many were found difficult to train as adults. These pups in many respects were similar to the deprived children. They acted as if they had become institutionalized, preferring the routine and safe environment of their kennel to the stimulating world outside their immediate place of residence.

Regular trips to the park, shopping centers and obedience and agility classes serve as good examples of enrichment activities. Chasing and retrieving a ball on the surface seems to be enriching because it provides exercise and includes rewards. While repeated attempts to retrieve a ball provide much physical activity, it should not be confused with enrichment exercises. Such playful activities should be used for exercise and play or as a reward after returning from a trip or training session. Road work and chasing balls are not substitutes for trips to the shopping mall, outings or obedience classes most of which provide many opportunities for interaction and investigation.

Finally it seems clear that stress early in life can produce beneficial results. The danger seems to be in not knowing where the thresholds are for over and under stimulation. However, the absence or the lack of adequate amounts of stimulation generally will produce negative and undesirable results. Based on the above it is fair to say that the performance of most individuals can be improved including the techniques described above. Each contributes in a cumulative way and supports the next stage of development. |

|

Conclusion

|

|

Breeders can now take advantage of the information available to improve and enhance performance. Generally, genetics account of about 35% of the performance but the remaining 65% (management, training, nutrition) can make the difference. In the management category it has been shown that breeders should be guided by the rule that it is generally considered prudent to guard against under and over stimulation. Short of ignoring pups during their first two months of life, a conservative approach would be to expose them to children, people, toys and other animals on a regular basis. Handling and touching all parts of their anatomy is also necessary to learn as early as the third day of life. Pups that are handled early and on a regular basis, generally do not become hand shy as adults.

Because of the risks involved in under stimulation a conservative approach to using the benefits of the three stages has been suggested based primarily on the works of Arskeusky, Kellogg, Yearkes and the “Bio Sensor” program (later known as the “Super Dog Program”).

Both experience and research have dominated the beneficial effects that can be achieved via early neurological stimulation, socialization and enrichment experiences. Each has been used to improve performance and to explain the differences that occur between individuals, their trainability, health and potential. The cumulative effects of the three stages have been well documented. They best serve the interests of owners who seek high levels of performance when properly used. Each has a cumulative effect and contributes to the development and the potential for individual performance. |

|

REFERENCES:

|

|

-

Battaglia, C.L., “Loneliness and Boredom” Doberman Quarterly, 1982.

-

Kellogg, W.N. & Kellogg, The Ape and the Child, New York: McGraw Hill. Scott & Fuller, (1965)

-

Dog Behavior -The Genetic Basics, University Chicago Press Scott, J.P., Ross, S., A.E. and King D.K. (1959)

-

The Effects of Early Enforced Weaning on Stickling Behavior of Puppies, J. Genetics Psychologist, p5: 261-81.

|

|

- originally published as “Early Neurological Stimulation”

- reprinted with permission by Dr. Carmen L. Battaglia

- photos and articles submitted by Marj Brooks, USA

|

Behavior, Breeder/Exhibitor Ed

…remember, your dog thinks you are god!

Much like a child, the early part of the life of your dog will be spent learning and deciding about the world. Those first months and years, will determine whether your dog sees the world as safe and friendly or hostile and scary, reliable or unpredictable. Clearly these factors will go a long way toward earning the title “good dog”.

Even older dogs, like older people, can have this perception impacted by effort and caring, but to get it done right in the beginning is easier and far less stressful.

So, upon bringing your dog home for the first time, regardless of their age, making an effort to introduce them to as many new and interesting aspects of their new life as possible is critical and invaluable. This is called socialization.

As you direct the socialization process, it is critical that you understand that a frightened or hesitant puppy will not be reassured by your frustration or anger or irritation. If you don’t have the time today to work through an issue as it presents itself, work on something else. If socialization is not pleasant, it will have the opposite of the desired effect.

The process in the mind of your dog, or a hesitant dog is “I don’t know, this doesn’t look right or feel right, I bet something bad might happen…” then you get upset. your dog was proven correct and you will be hard-pressed to change their mind in the future. Do not fall into this trap.

So, as you introduce your dog to a new situation, item or experience or thing, take the time to only praise the desired response and to sit patiently and ignore undesirable ones. If your dog should panic, try to remove as far from the stimulus as possible while your dog is still aware of it and ignore the tantrum. Do not make the mistake of attempting to reassure your dog. This may seem an unkindness but there is no evidence that dogs grasp the concept of reassurance. They do understand reinforcement however, and if your consoling makes them feel good about anxiety and panic, you can actually train your dog to be anxious and worried!

For example, your dog is on a leash and you are approaching a fire hydrant. your dog is unaware until you are about five feet away and then, they panic! Try quickly dropping back to ten or fifteen feet and assess how your dog relaxes. Don’t say anything and don’t touch your dog. Watch for indications that they are calmer. Once they have their composure, step closer to the hydrant and get their attention. If they will look at you (and thus see the hydrant in the background) praise that and step back to them for a pat or other reinforcement. As they recognize they have control (you will back up again if necessary) they will usually deem to investigate. This process may take several visits, until one day, you can sit on the hydrant while they come up and sniff, unconvinced but not panicking. After that, regular exposure as you just walk past it, ignoring it (some of the time) will help them recognize it is an unimportant land feature.

Giving your dog the opportunity to deal with their anxiety on their terms and at their pace accomplishes a number of things. It helps them trust you, as you are not forcing them into terrifying situations. They gain a sense of their own judgment as they weigh and determine how to approach new and potentially dangerous things. They gain coping skills as you don’t let them use their panic as a way to escape. Finally, they gain confidence as their experiences prove positive and their judgment proves sound.

Now that you know how to address the responses of your dog to novel experiences, it is time to compile as extensive a list as possible of places, people and things to see. Don’t overlook minor experiences like umbrellas and hats, don’t forget noises (trains, planes and automobiles), don’t overlook pet friendly places like shopping centers and pet supply shops and feed stores. Definitely think of people you know, big, small, loud, quiet, those with crutches, walkers, wheelchairs, big flapping coats and more. All of these things, while they may seem similar to us can seem dramatically different to your dog. Their sensory skills process things very differently.

You may even want to keep a journal of your efforts with your dog. It will be entertaining to reminisce when your dog is older about some of the funny things they did when seeing an aquarium for the first time. And it will also help you keep in mind experiences that you want to revisit as your dog finds some things more challenging than others.

Behavior, Breeder/Exhibitor Ed

Play.

How can it be that any living creature is without the knowledge of how to play? Wouldn’t that be akin to not knowing how to have fun or relax or be happy or laugh? Well, you’ve probably met people who didn’t seem to know how either, so let’s not be too hard on the dogs that missed out on that class. Most critically, proper play skills are extremely important to a happy, well-balanced and confident dog. Without proper play skills, training can be compromised and the dog will likely even suffer from poor social skills with other dogs. Thankfully, these skills are readily learned and fun to teach.

In truth, puppies that are without playmates during critical periods of their life, probably somewhere in the 6 weeks to 6 months range, would lack a lot of the opportunity to learn how to play. For dogs, play is something initiated in puppyhood. It hearkens back to the wild dogs who would learn their initial hunting and defence skills from play with their littermates and mother.

Regardless of the age of your dog, presuming they are in good health, you can probably help them learn some fundamental play skills. It is important that you keep your dog’s basic drives and behaviors in mind while you work to develop play. Virtually every dog has behaviors that could be built into playing but some of those behaviors could also go a bit too far to create a new set of problems (such as the dog that is a bit mouthy could become more uninhibited and mouthy as a result of such encouragement).

Basic theory would suggest that you observe your dog and determine things that they find some interest in, sniffing the ground, chasing the occasional butterfly, whatever the minor activity might be that could give you clues to what they find fascinating. From there, you want to determine how you could encourage the behavior. The dog that likes to sniff the grass might be intrigued by something you could drag through the yard. The combination of movement and scent would be too wonderful to ignore. Or feel free to try and intrigue them with a variety of props. Consider smearing peanut butter on a chew bone to get the dog more interested, put duck scent on a stuffed toy to see if they find that compelling enough to follow around when you play a bit of keep away. Try hiding toys around the house in relatively easy to find places (they are new to this after all). Make sure you and everyone else makes a huge fuss when they find your hidden treasures. You can be sure they will be always searching. Your creativity combined with the dog’s essential nature will help you down the path.

Secondary to this endeavor is to avoid overdoing it. If you get your dog to play with you for a couple minutes and they’ve never played much before, it’s time to stop. Don’t go to the point where they end the game or they will see play as work. Try to leave them wanting more.

Play is also a great part of socializing. Once your dog realizes that you have all these interesting tricks up your sleeve, they can’t help but figure every walk will be an adventure. Offering a toy when they deal with new experiences (fire hydrants, playground equipment) and letting new people they meet give them a small treat will go a long way toward developing and enthusiastic response to new things.

If your dog has a strong prey drive, you likely won’t need much help teaching them how to play, but you may need to help them find another game than tag (and rip a hole in your pants). Some games are not good choices for some dogs as they can encourage undesirable behaviors such as tag and tug of war. This is not to say that they should not be utilized but they would probably serve best if an experienced trainer was involved in their implementation. Virtually any game can be given an on/off switch. Once you do that, playing almost any game, even tag and tug of war, needn’t be an issue.

Once you’ve taught your dog to play, the biggest challenge might be in controlling their creativity. Someone once taught their dog the hide and seek game above. One evening during dinner, the dog collected virtually everything they could find that wasn’t too big or nailed down, and piled it up under their playmate’s chair. Another dog figured out that if her owner put on socks, that the boots would follow and they would go outside and play. That dog was quite a pest if she found a sock! Even so, neither owner would have ever traded their companion for a pile of gold. With that said, you may still want to consider the potential consequences if a favorite game became a consuming passion!

Behavior, Breeder/Exhibitor Ed

Many things are written regarding the hierarchy of dominance and submission, the fundamental aspects of the dog pack. Many people are left thinking that the environment they offer has to be a cross between boot camp and an inhumane prison in order for the dogs to understand that the people in their life are dominant.

So prior to offering suggestions on effective tools for building a happy pack, we probably need to discuss the differences in how dogs view their home life and address the questions that the previous paragraph might raise.

Dogs, wild dogs particularly, will establish a den but in contrast to people they are relatively willing to move. They need to stay where the food is, falling in love with a great view or location or floor plan isn’t practical to survival. As such, your dog considers him/herself “home” when they are around you. Utilizing this point of view is an incredibly valuable training tool since it can help signal encouragement and confidence in new situations or mild correction (unless they are a bit neurotic) if you should walk away. It also means that the defining point of your pack has less to do with what room you put the dog in or whether or not they are allowed on the furniture than many would think. This issues that arise from things like being allowed on the furniture come not from the geography (are they on the couch), rather it is an offshoot of who had the authority to allow it. Because that Pekingese on the bed determined he could be on the bed and no one had a right to question it, he now growls when disturbed, for example. Keeping this in mind will go a long way toward helping you assess what you are communicating to your dog in a given situation.

Now, think of your favorite authority or parental figure. They could have been you own parents or someone else’s, a coach, teacher or even a character in a book or in a movie. Odds are, they were greatly enthusiastic of the efforts and accomplishments of the children and other people around them. Their ability to discern that support and guidance might be needed did not distract them from those occasions that required a stern enforcer of fundamental rules. Otherwise, because of their confidence and general regard for others, they didn’t find it necessary to regularly insist on every nuance of their authority. If someone clearly worked around the rules, however, they were quick to re-establish the importance of those rules.

In much the same way, you will see a confident alpha dog be quite agreeable to behaviors of other, more “subordinate” dogs in the pack during times of play or when the pack is happy and well established. There is nothing like watching the alpha allow a young juvenile to take a toy from their mouth to put much of what has been written about submission/dominance on its ear.

Additionally, and this seems clearly a helpful survival tool for wild dogs, you will see the pack defer to different members as the alpha on given situations. Much as you might defer to one or another person at work depending on the question at hand. If someone is clearly skilled in one area or another, it strengthens the pack (or team) in addressing questions appropriately to them rather than relying exclusively upon the ideas of someone who isn’t as knowledgeable.

So after reading all this, you might be thinking, gee, sounds like a parent! Well, yes, a good parent. Within most happy families there are rules of what you must do, be honest and respectful; and rules that can be bent on occasion, like staying up late; but even then, those rules that can be bent are only done with the approval of a parent.

This requires the determination of the home you want to have and the type of “parent” you want to be. Offering those firm and fast rules or the structure and techniques you want to use is difficult. Add to the mix, that you might bring home a confident, strong-willed puppy or an independent, poorly mannered juvenile or a puppy with a very soft temperament lacking in assurance and socialization and the question of correct handling becomes much more challenging.

Assessing your puppy is something that is difficult to do. While an experienced trainer or breeder can work with a puppy and offer some insights, the fact is that puppy’s change a lot and constantly. Today’s confident, take on the world puppy, can be fearful and overwhelmed tomorrow. Consider adopting a juvenile and while they won’t be as quick to vary their outlook, they likely will have a history that you won’t be aware of, which can create more mystery in some of their behavioral responses. Don’t despair, however, dogs are far more forgiving than people. They respond well to consistent handling and can live their lives without looking back and blaming their mothers!