Killed By Kindness

Reproduced by permission from “Dogs in Review”, authored by Bo BengtsonJanuary 2012 issue of “Dogs in Review”

You have no doubt heard about the stud dog who was so valuable that he was not allowed to breed bitches except through artificial insemination. It turned out later that he was not capable of breeding on his own at all, and neither were most of his sons. There was also a famous bitch who was not allowed to whelp naturally, because who knows what damage that could have done, so she gave birth to her first litter by C-section — then to three more, also via C-section. And, big surprise, some of her daughters proved unable to whelp naturally. And there was the Best in Show winner who was so precious her owners did an embryo transfer, so their beautiful bitch would be spared the travails of pregnancy — which, of course, means nobody knows what kind of mother she would have been.

When you mess with Mother Nature, as we dog breeders have been doing with varying degrees of success for 150 years now, eventually there’s a price to pay. I seem to hear more often than I used to about dogs who are not able to breed naturally, bitches who have difficult whelpings and don’t know the basics of motherhood. With the advances of veterinary care, somehow there are usually live puppies anyway in the end… but at what price for the future of the species?

It was refreshing to read that one (but only one) of the seven finalists interviewed for AKC’s “Breeder of the Year” award mentioned a strong reproductive drive and good maternal instincts among the prime considerations when selecting breeding stock. How common are those priorities among show people these days, though? I overheard a couple of successful breeders at a show extolling the wonders of C-sections recently: just let the veterinarian take care of it! Much more practical than a messy natural whelping… but it’s not exactly how things were meant to be, is it?

We’re all a little guilty, I guess: we love our dogs, want to make things easy for them, are eager to make sure that even the weakest puppy of the litter survives. Who knows, after endless efforts that puppy may actually make it, grow up to become a beautiful champion — and continue to reproduce the species, with or without any immediate damage done to its breed.

No, I’m not advocating a return to the days of rough natural selection when a breeder basically peeked into the kennel and thought, “Hmm… Looks like Lizzie had her pups. We’ll see in a couple of weeks what she got!” I certainly don’t have the stomach to just “bucket” a weak puppy. But I am wondering if in the long run we’re doing ourselves and our dogs a disservice by not focusing more on their ability to reproduce naturally, with a minimum of human interference. There are no Best in Show awards for this, but perhaps there ought to be.

Oh, for the record: those dogs I mentioned at the beginning of this column are purely apocryphal: they don’t exist. Their counterparts do, though, and I bet you know at least some of them…

Designer Genes: Genetic Management or Misery

In the early 1970s, Miniature Schnauzer breeders embarked on a program unprecedented and unduplicated in any popular breed: to eliminate the genetic defect that caused juvenile cataracts. Research had established that juvenile cataracts (CJC) were transmitted as autosomal recessive with complete penetrance and were present at birth. Early diagnosis permitted the use of test-breeding, sanctioned by the national breed clubs, in which certified affected dogs were paired with mates whose status was unknown. A litter of normal eyed puppies was known to generate a mathematical probability that the tested dog was clear (the more normals, the better his or her odds), while the diagnosis of a single affected puppy proved the dog a carrier.

There is no argument that the program met its goals. A breed with an estimated 40% carrier rate emerged from two decades of test breeding with show lines cleared of the defect. It was a spectacularly successful example of how a breeding community can come together to eradicate a defect… and cause devastating damage to the gene pool.

Enter Stage Left

It has been written that, as a result of the process to eliminate CJC, over 200 American Champions were retired from breeding. Important kennels quietly closed up shop, taking distinct family branches with them, and bitches were sent exclusively to test-bred stud dogs. It was a lonely time for an untested male.

Around the same time as CJC was defeated, PRA made its entrance. In a few short years, several leading sires were revealed to be carriers and retired. There was no test-breeding program for this late onset defect, so it became a lonely time for the stud dog or bitch with a carrier ancestor. The gene pool contracted again.

Had this been the end of the troubles, there may have been time to pause and reflect on what was happening in the big picture, but this was not to be. A novel defect appeared on the scene – a muscular disorder called myotonia congenita. This problem found a solution in short order as a DNA test was developed, allowing breeders to identify carriers with a simple blood test. Those were retired, too. My choice of the word “retired” has, of course, been deliberately inappropriate here. In the world of dogs, “retired” is usually a euphemism for “sterilized”. As a device for preventing genetic defects, it must rate as one of the most destructive practices ever employed.

In a sensible dog world, quality carriers of genetic disease might be pulled from widespread use, but they’d come out of “retirement” for special occasions (i.e., for research breedings and/or the general advancement and preservation of rarer family lines). However, the dog fancy – and, by extension, breed clubs – have never been famous for our ability to apply knowledge sensibly. There is a common caution against throwing the baby out with the bathwater. In purebred dogs, there is a tendency to gather up the siblings, cousins and parents and throw them into the dustbin as well. We “improve” our breeds by killing them off one family branch at a time.

When I first began breeding nearly 30 years ago, I accepted the conventional wisdom that largely prevails to this day – that genetic defects are the exception, that carriers should be removed from the gene pool and that health is more important than beauty. But, as John Maynard Keynes said: “When somebody persuades me that I am wrong, I change my mind. What do you do?”

Managing the Unmanageable

A few years ago, some bright bulb at the Canadian Kennel Club launched a grand scheme to create a Code of Ethics. One of the rules proposed for this set of stone tablets was “Thou shalt not breed a carrier”. I recall writing to one of the Board members at the time to congratulate the CKC for devising an edict that would result in the immediate eradication of a number of breeds. For there are breeds today in which every single member is not merely a carrier, all or nearly all are affected with a genetic defect. The peculiar nature of Dalmatian urine chemistry is the most famous example.

Even in breeds with more moderate disease rates, the policy would have eventually resulted in genetic collapse and extinction. That’s because every normal living being is thought to carry in the range of 5 disease mutations in their DNA. In breeds with few founders and extreme bottleneck events, that average may be much higher. As molecular genetics digs into the DNA of our four footed friends, it is revealing gene frequencies that are nothing short of staggering in some breeds. In English Springer Spaniels, for example, a mutation that elevates the risk of PRA has been identified and a DNA test developed at the University of Missouri-Columbia. Of the dogs tested, only 20% have been found to be clear of the gene while over 40% tested as affected. Dobermans have similar carrier rates for the bleeding disorder, vWD.

Time for a Change?

The purpose of this article is not to cover the ground of nuts and bolts genetics. There’s simply not enough space and I don’t have the right letters after my name. There are many good texts available that cover the science, as well as a number of authoritative Internet sources. It is recommended that you seek the most recent material you can find as many of the popular canine genetics books of the past are now obsolete.

What I hope to provoke is an examination of some of our traditionally held beliefs. “Thou shalt not breed a carrier” served us well enough when diagnostics were primitive, most carriers escaped detection, and conditions now known to be inherited were dismissed as environmental or simple bad luck. This is no longer the case.

Unfortunately, a little knowledge can be dangerous. The discovery of extreme carrier rates in a breed has the potential to overwhelm breeders who have always held that their primary goal was to produce healthy dogs. It’s depressing to think of how many aspiring breeders accepted as an article of faith that quality foundation stock, good intentions and careful testing would result in good health – only to fail. They’d start over, fail again, become discouraged and move out of the sport. Now we know why.

The bottom line is that much of what we thought was wrong. Now, for the sake of our breeds, we need to change our minds. It is no longer a question of “eliminating” gene defects from a breed. We can only ask which ones, how quickly and should we even try? For this reason, it is imperative that breed clubs take the lead and reform outdated notions about “ethical” breeding practices and the advisability of “retiring” animals before they can leave positive contributions to the gene pool.

Diversity is Key

One of the most important factors in maintaining a healthy breed population is preserving genetic diversity. Genetic diversity is important for survival and adaptability within species, but dog breeds are not species. They are purpose-bred populations that have undergone selection for specific traits or behaviours. It is not enough to simply survive; they have a job to do. Nonetheless, within closed gene pools, genetic diversity is central to infectious disease resistance and the availability of normal alleles when mutations arise.

There is little disagreement on that point, but there can be great disagreement on the best means to achieve it. One camp believes in outcrossing, de-emphasis of “show ring” traits and performance standards, and even selected infusions of other breeds. Another camp holds that a healthy diversity of successful breeders who work to preserve and develop distinct family lines is the best way to preserve genetic choice. I happen to belong to the latter.

Before one begins, however, one must first define “successful”. Or rather, one must understand how success is defined in any breed. It is not a matter of interpretation; it is a matter of record.

A few years after I began showing and breeding Miniature Schnauzers, I realized that no historical archives existed for champion producers in Canada, in

the way they have always been catalogued in the US. So, I began gathering the data from old CKC stud books and issues of Dogs In Canada, starting with the first recorded champion in 1933.

Somewhere in the middle of the project, I had an epiphany. Everything that I had been told to believe was wrong: Health is not more important than beauty. Beauty is more important than health.

Next Issue: It isn’t important that we all do the right thing, it is only important that we don’t all do the wrong thing. Forcing everyone to do the same thing risks forcing everyone to do the wrong thing.

Designer Genes Beauty vs. Health, part2

Somewhere in the middle of the project, I had an epiphany. Everything that I had been told to believe was wrong. Health was not more important than beauty…beauty was more important than health.

As I recorded the names of champion offspring of those dogs of the past, I began to notice patterns. Kennels would emerge, win well for a time, and then fade away upon the arrival of new competition with better winning stock. The majority of sires and dams that had produced multiple champions in their day were virtually absent in modern show pedigrees. Their lines had, for all intents and purposes, become extinct.

As it turned out, the most reliable asset a line could possess wasn’t the ability to produce large litters without assistance, live to a ripe old age, or pass a series of health clearances. It was that someone had to want to breed them, and then actually breed to them.

The Human Factor

Breeding dogs for the competitive arena is labour intensive and expensive. With little chance of profit, the motivations are largely esoteric – goal attainment, pride in performance, thrill of competition, appreciation of beauty and form. Bloodlines that fulfill these ambitions tend to grow and expand their share of the gene pool, while those that don’t, wither away or are relegated to producing puppies for the pet market. It’s not to say that winning is the only thing that matters, but it’s fair to say that nothing else matters as much. For, while gene defects may slow the expansion of a winning family into other lines or force it in a new direction, ugly is fatal.

Each time we are confronted with genetic disease, whether it be in the role of individual breeder, mentor or breed club, it is this “human factor” that must always remain front and center.

Programs designed to reduce defects in a breed or a family, while absolutely necessary for long-term health and control of gene frequencies, must never be permitted to subordinate the quality of animals, or the ability of individual breeders to achieve their aims. Without quality, the line will not survive future selection pressures. Without quality, breeders will find themselves hard pressed to continue.

It is not good enough to promise a light at the end of the tunnel. Those lights must remain on along the route so that individuals are reminded that there is more to breeding dogs than avoiding the bad.

That of course, doesn’t grant us license to ignore our problems, or worse yet, to conceal information. Without open and frank disclosures, the very risk reduction strategies that allow breeders to manage disease frequency are impossible.

The first priority for breed clubs is to update our old strategies and accept that genetic disease is a normal part of the makeup of good dogs. While normalizing defects may seem heresy to some, it is only through accepting there is no such thing as a “clear” dog that modern breeding programs will survive the wave of information that is beginning to come ashore. As previously mentioned, new DNA tests are uncovering gene frequencies in some breeds that have the potential to result in the total collapse of gene pools, if efforts at reduction are not carried out with extreme caution. It’s imperative that breed clubs get out ahead of this, and begin the re-education process now.

Of course, talking about transformation is easy; putting it into practice at the kennel level, much harder.

Reality Bites

“I just got back from the clinic. I don’t know what to do.”

Anyone who has found themselves slumped in a chair with a CERF form in one hand and a drink in the other knows the feeling.

For a disturbingly large segment of the fancy, the only “ethical” response is to search for a sword to fling one’s breeding program upon – the more publicly, the better. Not because it’s the logical, rational thing to do, but so that they may hold themselves up as morally superior. Every breed club has influential members who hold these well-intentioned, but destructive views. It’s time to confront them with reason.

Defective genes have been part of the makeup of breeds for scores of generations. Most became widespread long before veterinary science had the ability to identify, diagnose and treat them, and those breeds managed to survive. Your breeding program can survive, too – but it’s up to you.

There is no need to cure Rome in a day. Nor is there any need to sacrifice the best animals in a breeding program to avoid criticism from the uninformed and just plain vindictive among your peers. Pleasing your enemies does not turn them into friends.

The first step, particularly for the novice breeder who is facing genetic disease for the first time, is to give yourself breathing room. Take no action until your emotions are under control. Go to the field trial, continue your coat work, enter the shows you had planned. Your kennel’s participation in the competitive arena should not change because you’ve had a bad diagnosis – indeed, this is when you most need to remind yourself of the rewards that come from your involvement in dogs. Certainly, some exhibitors may beak and complain. Ignore them.

Take a few weeks to research the defect and your pedigrees. Ask yourself a list of questions designed to determine to what extent the defect can be tolerated in your breeding program, if it must be tolerated, and what impact you will allow it to have on future breeding plans.

1. Does the defect cause significant for pain or reduction in lifespan of the dog? Do affected animals pose a risk to others (aggression behaviors, etc.)? Do effective treatments exist? If chronic, is it difficult or expensive to diagnose or treat?

Generally, the more serious the effect on the dog’s well-being and the owner’s pocketbook, the less likely you or others will want to risk producing others who might suffer from it.

2. Is the problem common in your breed or the family line? Is it rare? Does it represent something new?

There may be nothing to gain from retiring a dog because he carries a gene that’s prevalent in the gene pool. Removing him won’t reduce the gene frequency, controlled breeding won’t increase it. It may be the “cost of doing business” in that line or breed until improved screening protocols come along. Learning to live with it may be the only choice available.

Conversely, the dog that carries a novel defect has the potential to transform a rare mutation into a common one. Such a dog is capable of raising gene frequencies and introducing disease into lines that are currently clear from it, so must be handled with discretion if bred.

3. Can it be diagnosed in a puppy, or does it show up after the dog is placed in a home, or has embarked on a breeding career?

The earlier a defect can be diagnosed, the easier it is to manage in a breeding program. The pain isn’t visited on buyers and the issue remains a “breeder’s problem”.

4. Is the mode of inheritance known?

The more one knows about the mode of inheritance, the easier it is to balance pedigrees and work around, or even eliminate a problem. (If not, don’t draw conclusions as to the genetic status of the parents and offspring. Some modes of inheritance are quite complex, and expression intermittent.)

When those questions have been considered, they must be placed into context:

1.

What is the quality of the affected/carrier animal? Does it possess outstanding virtues or is it just average? What does the rest of the health and genetic profile look like? Is it likely to produce puppies that are worth the effort?

2. Is the affected animal from a prosperous family line, or is it rare?

This may require digging deep into your pedigrees, as few modern breeders or even breed clubs are as aware of the originating lines of their breed as they should be. > Rare and distinct family lines may carry valuable alleles important to the genetic diversity and future health of the breed and their extinction should be avoided at all costs. Line preservation trumps genetic disease concerns in all but the most extreme cases. These are the dogs for which the “baby and bathwater” analogy was created.

Decision Time

So, let us return to our breeder’s CERF form, now that the drink is finished.

In this simplified example, the dog has been diagnosed with cataracts. Cataracts are fairly frequent in the breed. While some research is underway, no DNA test exists. Not much is known about the inheritance, other than it appears to be familial. Cataracts can result in complications and surgery, but most affected dogs live fairly normal lives despite them.

Now, what about the dog and her pedigree?

As you may have deduced, there is no one answer that fits all.

A) The bitch is from a popular line. She’s of good quality, but not exceptional. She has a normal-eyed half sister who is two years older. The breeder decides to spay her – there’s more where she came from.

B) The bitch is fabulous, with an impressive show career. She’s from a popular line, but has never been bred. The breeder chooses a complimentary sire of a line with low incidence of cataracts, with the goal of producing a daughter he can carry on with.

C) The bitch is the last daughter of a rare branch of the breed. She is of good quality and general health. The breeder decides to line breed her to a CERF normal sire who is well up in years, that compliments her type and fortifies her unique pedigree.

All have made rational decisions. Breeding the average bitch from a popular line isn’t likely to advance anyone’s interests. Spaying an exceptional bitch without ensuring she has a chance to pass on her virtues is not in the long-term interests of any breed. (Mediocre dogs carry disease genes, too!)

The breeder who goes on with an affected bitch from a threatened line also has his priorities straight. When in doubt, advance the line. A carrier son or daughter might some day produce puppies that test clear, but quality descendants must exist, or there will be nothing to test.

None of these strategies suggest that a dog with a serious genetic defect should be offered at public stud, or his puppies sold to prolific kennels. But between popular sire and sterilization is a very large middle ground in which dogs that are not suitable for wide use can still make a positive contribution.

As breeders, we have been entrusted with something very precious – a bitch line. Every time one of us fails to produce dogs of sufficient quality to carry it forward, we fail that trust. When we become lazy and indifferent about promoting our good dogs to others, we fail again. The daughter of the daughter fails to produce a daughter that carries on, another branch of the breed dies and the gene pool narrows a tiny bit more.

Doing the “Right” Thing

When managing genetic disease, there is seldom a “one size fits all” solution. Breed clubs need to recognize that individuals have different priorities and challenges, and accommodate this when issuing recommendations.

Most of all, we must recognize the absolute importance of the “human factor” in preserving families and advancing breeds. Breeders are most motivated when they are breeding for something – towards the good, not away from the bad. We need to acknowledge the power of beauty to inspire us, and pledge never to ask a colleague to give up on a dog or a line that they love in the pursuit of a goal that is unattainable – the disease-free breed.

And we must forgive each other’s mistakes, for despite our best breeding intentions, there will be many.

It’s not important that we all do the right thing – it’s only important that we don’t all do the wrong thing. When we force all breeders to do the same thing, we risk forcing all breeders to do the wrong thing.

As for those two hundred champions that were retired from my breed to eliminate a single gene? I often wonder where we could have been today if only a handful of the best had been bred one or two times more.

Long-Term Health Risks and Benefits Associated with Spay / Neuter in Dogs

May 14, 2007

Precis

At some point, most of us with an interest in dogs will have to consider whether or not to spay / neuter our

pet. Tradition holds that the benefits of doing so at an early age outweigh the risks. Often, tradition holds

sway in the decision-making process even after countervailing evidence has accumulated.

Ms Sanborn has reviewed the veterinary medical literature in an exhaustive and scholarly treatise,

attempting to unravel the complexities of the subject. More than 50 peer-reviewed papers were examined to

assess the health impacts of spay / neuter in female and male dogs, respectively. One cannot ignore the

findings of increased risk from osteosarcoma, hemangiosarcoma, hypothyroidism, and other less frequently

occurring diseases associated with neutering male dogs. It would be irresponsible of the veterinary

profession and the pet owning community to fail to weigh the relative costs and benefits of neutering on the

animal´s health and well-being. The decision for females may be more complex, further emphasizing the

need for individualized veterinary medical decisions, not standard operating procedures for all patients.

No sweeping generalizations are implied in this review. Rather, the author asks us to consider all the health

and disease information available as individual animals are evaluated. Then, the best decisions should be

made accounting for gender, age, breed, and even the specific conditions under which the long-term care,

housing and training of the animal will occur.

This important review will help veterinary medical care providers as well as pet owners make informed

decisions. Who could ask for more?

Larry S. Katz, PhD

Associate Professor and Chair

Animal Sciences

Rutgers University

New Brunswick, NJ 08901

INTRODUCTION

Dog owners in America are frequently advised to spay/neuter their dogs for health reasons. A number of

health benefits are cited, yet evidence is usually not cited to support the alleged health benefits.

When discussing the health impacts of spay/neuter, health risks are often not mentioned. At times, some

risks are mentioned, but the most severe risks usually are not.

This article is an attempt to summarize the long-term health risks and benefits associated with spay/neuter

in dogs that can be found in the veterinary medical literature. This article will not discuss the impact of

spay/neuter on population control, or the impact of spay/neuter on behavior.

Nearly all of the health risks and benefits summarized in this article are findings from retrospective

epidemiological research studies of dogs, which examine potential associations by looking backwards in

time. A few are from prospective research studies, which examine potential associations by looking forward

in time.

SUMMARY

An objective reading of the veterinary medical literature reveals a complex situation with respect to the longterm

health risks and benefits associated with spay/neuter in dogs. The evidence shows that spay/neuter

Page 2 of 12

correlates with both positive AND adverse health effects in dogs. It also suggests how much we really do

not yet understand about this subject.

On balance, it appears that no compelling case can be made for neutering most male dogs, especially

immature male dogs, in order to prevent future health problems. The number of health problems associated

with neutering may exceed the associated health benefits in most cases.

On the positive side, neutering male dogs

• eliminates the small risk (probably <1%) of dying from testicular cancer

• reduces the risk of non-cancerous prostate disorders

• reduces the risk of perianal fistulas

• may possibly reduce the risk of diabetes (data inconclusive)

On the negative side, neutering male dogs

• if done before 1 year of age, significantly increases the risk of osteosarcoma (bone cancer); this is a

common cancer in medium/large and larger breeds with a poor prognosis.

• increases the risk of cardiac hemangiosarcoma by a factor of 1.6

• triples the risk of hypothyroidism

• increases the risk of progressive geriatric cognitive impairment

• triples the risk of obesity, a common health problem in dogs with many associated health problems

• quadruples the small risk (<0.6%) of prostate cancer

• doubles the small risk (<1%) of urinary tract cancers

• increases the risk of orthopedic disorders

• increases the risk of adverse reactions to vaccinations

For female dogs, the situation is more complex. The number of health benefits associated with spaying may

exceed the associated health problems in some (not all) cases. On balance, whether spaying improves the

odds of overall good health or degrades them probably depends on the age of the female dog and the

relative risk of various diseases in the different breeds.

On the positive side, spaying female dogs

• if done before 2.5 years of age, greatly reduces the risk of mammary tumors, the most common

malignant tumors in female dogs

• nearly eliminates the risk of pyometra, which otherwise would affect about 23% of intact female

dogs; pyometra kills about 1% of intact female dogs

• reduces the risk of perianal fistulas

• removes the very small risk (_0.5%) from uterine, cervical, and ovarian tumors

On the negative side, spaying female dogs

• if done before 1 year of age, significantly increases the risk of osteosarcoma (bone cancer); this is a

common cancer in larger breeds with a poor prognosis

• increases the risk of splenic hemangiosarcoma by a factor of 2.2 and cardiac hemangiosarcoma by

a factor of >5; this is a common cancer and major cause of death in some breeds

• triples the risk of hypothyroidism

• increases the risk of obesity by a factor of 1.6-2, a common health problem in dogs with many

associated health problems

• causes urinary “spay incontinence” in 4-20% of female dogs

• increases the risk of persistent or recurring urinary tract infections by a factor of 3-4

• increases the risk of recessed vulva, vaginal dermatitis, and vaginitis, especially for female dogs

spayed before puberty

• doubles the small risk (<1%) of urinary tract tumors

• increases the risk of orthopedic disorders

• increases the risk of adverse reactions to vaccinations

One thing is clear – much of the spay/neuter information that is available to the public is unbalanced and

contains claims that are exaggerated or unsupported by evidence. Rather than helping to educate pet

Page 3 of 12

owners, much of it has contributed to common misunderstandings about the health risks and benefits

associated of spay/neuter in dogs.

The traditional spay/neuter age of six months as well as the modern practice of pediatric spay/neuter appear

to predispose dogs to health risks that could otherwise be avoided by waiting until the dog is physically

mature, or perhaps in the case of many male dogs, foregoing it altogether unless medically necessary.

The balance of long-term health risks and benefits of spay/neuter will vary from one dog to the next. Breed,

age, and gender are variables that must be taken into consideration in conjunction with non-medical factors

for each individual dog. Across-the-board recomm

endations for all pet dogs do not appear to be

supportable from findings in the veterinary medical literature.

FINDINGS FROM STUDIES

This section summarizes the diseases or conditions that have been studied with respect to spay/neuter in

dogs.

Complications from Spay/Neuter Surgery

All surgery incurs some risk of complications, including adverse reactions to anesthesia, hemorrhage,

inflammation, infection, etc. Complications include only immediate and near term impacts that are clearly

linked to the surgery, not to longer term impacts that can only be assessed by research studies.

At one veterinary teaching hospital where complications were tracked, the rates of intraoperative,

postoperative and total complications were 6.3%, 14.1% and 20.6%, respectively as a result of spaying

female dogs1. Other studies found a rate of total complications from spaying of 17.7%2 and 23%3. A study

of Canadian veterinary private practitioners found complication rates of 22% and 19% for spaying female

dogs and neutering male dogs, respectively4.

Serious complications such as infections, abscesses, rupture of the surgical wound, and chewed out sutures

were reported at a 1- 4% frequency, with spay and castration surgeries accounting for 90% and 10% of

these complications, respectively.4

The death rate due to complications from spay/neuter is low, at around 0.1%2.

Prostate Cancer

Much of the spay/neuter information available to the public asserts that neutering will reduce or eliminate the

risk that male dogs develop prostate cancer. This would not be an unreasonable assumption, given that

prostate cancer in humans is linked to testosterone. But the evidence in dogs does not support this claim.

In fact, the strongest evidence suggests just the opposite.

There have been several conflicting epidemiological studies over the years that found either an increased

risk or a decreased risk of prostate cancer in neutered dogs. These studies did not utilize control

populations, rendering these results at best difficult to interpret. This may partially explain the conflicting

results.

More recently, two retrospective studies were conducted that did utilize control populations. One of these

studies involved a dog population in Europe5 and the other involved a dog population in America6. Both

studies found that neutered male dogs have a four times higher risk of prostate cancer than intact dogs.

Based on their results, the researchers suggest a cause-and-effect relationship: “this suggests that

castration does not initiate the development of prostatic carcinoma in the dog, but does favor tumor

progression”5 and also “Our study found that most canine prostate cancers are of ductal/urothelial

origin….The relatively low incidence of prostate cancer in intact dogs may suggest that testicular hormones

Page 4 of 12

are in fact protective against ductal/urothelial prostatic carcinoma, or may have indirect effects on cancer

development by changing the environment in the prostate.”6

This needs to be put in perspective. Unlike the situation in humans, prostate cancer is uncommon in dogs.

Given an incidence of prostate cancer in dogs of less than 0.6% from necropsy studies7, it is difficult to see

that the risk of prostate cancer should factor heavily into most neutering decisions. There is evidence for an

increased risk of prostate cancer in at least one breed (Bouviers)5, though very little data so far to guide us

in regards to other breeds.

Testicular Cancer

Since the testicles are removed with neutering, castration removes any risk of testicular cancer (assuming

the castration is done before cancer develops). This needs to be compared to the risk of testicular cancer in

intact dogs.

Testicular tumors are not uncommon in older intact dogs, with a reported incidence of 7%8. However, the

prognosis for treating testicular tumors is very good owing to a low rate of metastasis9, so testicular cancer

is an uncommon cause of death in intact dogs. For example, in a Purdue University breed health survey of

Golden Retrievers10, deaths due to testicular cancer were sufficiently infrequent that they did not appear on

list of significant causes of “Years of Potential Life Lost for Veterinary Confirmed Cause of Death” even

though 40% of GR males were intact. Furthermore, the GRs who were treated for testicular tumors had a

90.9% cure rate. This agrees well with other work that found 6-14% rates of metastasis for testicular tumors

in dogs11.

The high cure rate of testicular tumors combined with their frequency suggests that fewer than 1% of intact

male dogs will die of testicular cancer.

In summary, though it may be the most common reason why many advocate neutering young male dogs,

the risk from life threatening testicular cancer is sufficiently low that neutering most male dogs to prevent it is

difficult to justify.

An exception might be bilateral or unilateral cryptorchids, as testicles that are retained in the abdomen are

13.6 times more likely to develop tumors than descended testicles12 and it is also more difficult to detect

tumors in undescended testicles by routine physical examination.

Osteosarcoma (Bone Cancer)

A multi-breed case-control study of the risk factors for osteosarcoma found that spay/neutered dogs (males

or females) had twice the risk of developing osteosarcoma as did intact dogs13.

This risk was further studied in Rottweilers, a breed with a relatively high risk of osteosarcoma. This

retrospective cohort study broke the risk down by age at spay/neuter, and found that the elevated risk of

osteosarcoma is associated with spay/neuter of young dogs14. Rottweilers spayed/neutered before one

year of age were 3.8 (males) or 3.1 (females) times more likely to develop osteosarcoma than intact dogs.

Indeed, the combination of breed risk and early spay/neuter meant that Rottweilers spayed/neutered before

one year of age had a 28.4% (males) and 25.1% (females) risk of developing osteosarcoma. These results

are consistent with the earlier multi-breed study13 but have an advantage of assessing risk as a function of

age at neuter. A logical conclusion derived from combining the findings of these two studies is that

spay/neuter of dogs before 1 year of age is associated with a significantly increased risk of osteosarcoma.

The researchers suggest a cause-and-effect relationship, as sex hormones are known to influence the

maintenance of skeletal structure and mass, and also because their findings showed an inverse relationship

between time of exposure to sex hormones and risk of osteosarcoma.14

Page 5 of 12

The risk of osteosarcoma increases with increasing breed size and especially height13. It is a common

cause of death in medium/large, large, and giant breeds. Osteosarcoma is the third most common cause of

death in Golden Retrievers10 and is even more common in larger breeds13.

Given the poor prognosis of osteosarcoma and its frequency in many breeds, spay/neuter of immature dogs

in the medium/large, large, and giant breeds is apparently associated with a significant and elevated risk of

death due to osteosarcoma.

Mammary Cancer (Breast Cancer)

Mammary tumors are by far the most common tumors in intact female dogs, constituting some 53% of all

malignant tumors in female dogs in a study of dogs in Norway15 where spaying is much less common than in

the USA.

50-60% of mammary tumors are malignant, for which there is a significant risk of metastasis16. Mammary

tumo

rs in dogs have been found to have estrogen receptors17, and the published research18 shows that the

relative risk (odds ratio) that a female will develop mammary cancer compared to the risk in intact females is

dependent on how many estrus cycles she experiences:

# of estrus cycles before spay Odds Ratio

None 0.005

1 0.08

2 or more 0.26

Intact 1.00

The same data when categorized differently showed that the relative risk (odds ratio) that females will

develop mammary cancer compared to the risk in intact females indicated that:

Age at Spaying Odds Ratio

_ 29 months 0.06

_ 30 months 0.40 (not statistically significant at the P<0.05 level)

Intact 1.00

Please note that these are RELATIVE risks. This study has been referenced elsewhere many times but the

results have often been misrepresented as absolute risks.

A similar reduction in breast cancer risk was found for women under the age of 40 who lost their estrogen

production due to “artificial menopause”19 and breast cancer in humans is known to be estrogen activated.

Mammary cancer was found to be the 10th most common cause of years of lost life in Golden Retrievers,

even though 86% of female GRs were spayed, at a median age of 3.4 yrs10. Considering that the female

subset accounts for almost all mammary cancer cases, it probably would rank at about the 5th most common

cause of years of lost life in female GRs. It would rank higher still if more female GRs had been kept intact

up to 30 months of age.

Boxers, cocker spaniels, English Springer spaniels, and dachshunds are breeds at high risk of mammary

tumors15. A population of mostly intact female Boxers was found to have a 40% chance of developing

mammary cancer between the ages of 6-12 years of age15. There are some indications that purebred dogs

may be at higher risk than mixed breed dogs, and purebred dogs with high inbreeding coefficients may be at

higher risk than those with low inbreeding coefficients20. More investigation is required to determine if these

are significant.

In summary, spaying female dogs significantly reduces the risk of mammary cancer (a common cancer),

and the fewer estrus cycles experienced at least up to 30 months of age, the lower the risk will be.

Page 6 of 12

Female Reproductive Tract Cancer (Uterine, Cervical, and Ovarian Cancers)

Uterine/cervical tumors are rare in dogs, constituting just 0.3% of tumors in dogs21.

Spaying will remove the risk of ovarian tumors, but the risk is only 0.5%22.

While spaying will remove the risk of reproductive tract tumors, it is unlikely that surgery can be justified to

prevent the risks of uterine, cervical, and ovarian cancers as the risks are so low.

Urinary Tract Cancer (Bladder and Urethra Cancers)

An age-matched retrospective study found that spay/neuter dogs were two times more likely to develop

lower urinary tract tumors (bladder or urethra) compared to intact dogs23. These tumors are nearly always

malignant, but are infrequent, accounting for less than 1% of canine tumors. So this risk is unlikely to weigh

heavily on spay/neuter decisions.

Airedales, Beagles, and Scottish Terriers are at elevated risk for urinary tract cancer while German

Shepherds have a lower than average risk23.

Hemangiosarcoma

Hemangiosarcoma is a common cancer in dogs. It is a major cause of death in some breeds, such as

Salukis, French Bulldogs, Irish Water Spaniels, Flat Coated Retrievers, Golden Retrievers, Boxers, Afghan

Hounds, English Setters, Scottish Terriesr, Boston Terriers, Bulldogs, and German Shepherd Dogs24.

In an aged-matched case controlled study, spayed females were found to have a 2.2 times higher risk of

splenic hemangiosarcoma compared to intact females24.

A retrospective study of cardiac hemangiosarcoma risk factors found a >5 times greater risk in spayed

female dogs compared to intact female dogs and a 1.6 times higher risk in neutered male dogs compared to

intact male dogs.25 The authors suggest a protective effect of sex hormones against hemangiosarcoma,

especially in females.

In breeds where hermangiosarcoma is an important cause of death, the increased risk associated with

spay/neuter is likely one that should factor into decisions on whether or when to sterilize a dog.

Hypothyroidism

Spay/neuter in dogs was found to be correlated with a three fold increased risk of hypothyroidism compared

to intact dogs. 26.

The researchers suggest a cause-and-effect relationship: They wrote: “More important [than the mild direct

impact on thyroid function] in the association between [spaying and] neutering and hypothyroidism may be

the effect of sex hormones on the immune system. Castration increases the severity of autoimmune

thyroiditis in mice” which may explain the link between spay/neuter and hypothyroidism in dogs.

Hypothyroidism in dogs causes obesity, lethargy, hair loss, and reproductive abnormalities.27

The lifetime risk of hypothyroidism in breed health surveys was found to be 1 in 4 in Golden Retrievers10, 1

in 3 in Akitas28, and 1 in 13 in Great Danes29.

Page 7 of 12

Obesity

Owing to changes in metabolism, spay/neuter dogs are more likely to be overweight or obese than intact

dogs. One study found a two fold increased risk of obesity in spayed females compared to intact females30.

Another study found that spay/neuter dogs were 1.6 (females) or 3.0 (males) times more likely to be obese

than intact dogs, and 1.2 (females) or 1.5 (males) times more likely to be overweight than intact dogs31.

A survey study of veterinary practices in the UK found that 21% of dogs were obese.30

Being obese and/or overweight is associated with a host of health problems in dogs. Overweight dogs are

more likely to be diagnosed with hyperadrenocorticism, ruptured cruciate ligament, hypothyroidism, lower

urinary tract disease, and oral disease32. Obese dogs are more likely to be diagnosed with hypothyroidism,

diabetes mellitus, pancreatitis, ruptured cruciate ligament, and neoplasia (tumors)32.

Diabetes

Some data indicate that neutering doubles the risk of diabetes in male dogs, but other data showed no

significant change in diabetes risk with neutering33. In the same studies, no association was found between

spaying and the risk of diabetes.

Adverse Vaccine Reactions

A retrospective cohort study of adverse vaccine reactions in dogs was conducted, which included allergic

reactions, hives, anaphylaxis, cardiac arrest, cardiovascular shock, and sudden death. Adverse reactions

were 30% more likely in spayed females than intact females, and 27% more likely in neutered males than

intact males34.

The investigators discuss possible cause-and-effect mechanisms for this finding, including the roles that sex

hormones play in body´s ability to mount an immune response to vaccination.34

Toy breeds and smaller breeds are at elevated risk of adverse vaccine reactions, as are Boxers, English

Bulldogs, Lhasa Apsos, Weimaraners, American Eskimo Dogs, Golden Retrievers, Basset Hounds, Welsh

Corgis, Siberian Huskies, Great Danes, Labrador Retrievers, Doberman Pinschers, American Pit Bull

Terriers, and Akitas.34 Mixed breed dogs were found to be at lower risk, and the authors suggest genetic

hetereogeneity (hybrid vigor) as the cause.

Urogenital Disorders

Urinary incontinence is common in spayed female dogs, which can occur soon after spay surgery or after a

delay of up to several years. The incidence rate in various studies

is 4-20% 35,36,37 for spayed females

compared to only 0.3% in intact females38. Urinary incontinence is so strongly linked to spaying that it is

commonly called “spay incontinence” and is caused by urethral sphincter incompetence39, though the

biological mechanism is unknown. Most (but not all) cases of urinary incontinence respond to medical

treatment, and in many cases this treatment needs to be continued for the duration of the dog´s life.40

A retrospective study found that persistent or recurring urinary tract (bladder) infections (UTIs) were 3-4

times more likely in spayed females dogs than in intact females41. Another retrospective study found that

female dogs spayed before 5 ½ months of age were 2.76 times more likely to develop UTIs compared to

those spayed after 5 ½ months of age.42

Depending on the age of surgery, spaying causes abnormal development of the external genitalia. Spayed

females were found to have an increased risk of recessed vulva, vaginal dermatitis, vaginitis, and UTIs.43

The risk is higher still for female dogs spayed before puberty.43

Page 8 of 12

Pyometra (Infection of the Uterus)

Pet insurance data in Sweden (where spaying is very uncommon) found that 23% of all female dogs

developed pyometra before 10 years of age44. Bernese Mountain dogs, Rottweilers, rough-haired Collies,

Cavalier King Charles Spaniels and Golden Retrievers were found to be high risk breeds44. Female dogs

that have not whelped puppies are at elevated risk for pyometra45. Rarely, spayed female dogs can

develop “stump pyometra” related to incomplete removal of the uterus.

Pyometra can usually be treated surgically or medically, but 4% of pyometra cases led to death44.

Combined with the incidence of pyometra, this suggests that about 1% of intact female dogs will die from

pyometra.

Perianal Fistulas

Male dogs are twice as likely to develop perianal fistulas as females, and spay/neutered dogs have a

decreased risk compared to intact dogs46.

German Shepherd Dogs and Irish Setters are more likely to develop perianal fistulas than are other

breeds.46

Non-cancerous Disorders of the Prostate Gland

The incidence of benign prostatic hypertrophy (BPH, enlarged prostate) increases with age in intact male

dogs, and occurs in more than 80% of intact male dogs older than the age of 5 years47. Most cases of BPH

cause no problems, but in some cases the dog will have difficulty defecating or urinating.

Neutering will prevent BPH. If neutering is done after the prostate has become enlarged, the enlarged

prostate will shrink relatively quickly.

BPH is linked to other problems of the prostate gland, including infections, abscesses, and cysts, which can

sometimes have serious consequences.

Orthopedic Disorders

In a study of beagles, surgical removal of the ovaries (as happens in spaying) caused an increase in the rate

of remodeling of the ilium (pelvic bone)48, suggesting an increased risk of hip dysplasia with spaying.

Spaying was also found to cause a net loss of bone mass in the spine 49.

Spay/neuter of immature dogs delays the closure of the growth plates in bones that are still growing,

causing those bones to end up significantly longer than in intact dogs or those spay/neutered after

maturity50. Since the growth plates in various bones close at different times, spay/neuter that is done after

some growth plates have closed but before other growth plates have closed might result in a dog with

unnatural proportions, possibly impacting performance and long term durability of the joints.

Spay/neuter is associated with a two fold increased risk of cranial cruciate ligament rupture51. Perhaps this

is associated with the increased risk of obesity30.

Spay/neuter before 5 ½ months of age is associated with a 70% increased aged-adjusted risk of hip

dysplasia compared to dogs spayed/neutered after 5 ½ months of age, though there were some indications

that the former may have had a lower severity manifestation of the disease42. The researchers suggest “it

is possible that the increase in bone length that results from early-age gonadectomy results in changes in

joint conformation, which could lead to a diagnosis of hip dysplasia.”

Page 9 of 12

In a breed health survey study of Airedales, spay/neuter dogs were significantly more likely to suffer hip

dysplasia as well as “any musculoskeletal disorder”, compared to intact dogs52, however possible

confounding factors were not controlled for, such as the possibility that some dogs might have been

spayed/neutered because they had hip dysplasia or other musculoskeletal disorders.

Compared to intact dogs, another study found that dogs neutered six months prior to a diagnosis of hip

dysplasia were 1.5 times as likely to develop clinical hip dysplasia.53

Compared to intact dogs, spayed/neutered dogs were found to have a 3.1 fold higher risk of patellar

luxation.54

Geriatric Cognitive Impairment

Neutered male dogs and spayed female dogs are at increased risk of progressing from mild to severe

geriatric cognitive impairment compared to intact male dogs55. There weren´t enough intact geriatric

females available for the study to determine their risk.

Geriatric cognitive impairment includes disorientation in the house or outdoors, changes in social

interactions with human family members, loss of house training, and changes in the sleep-wake cycle55.

The investigators state “This finding is in line with current research on the neuro-protective roles of

testosterone and estrogen at the cellular level and the role of estrogen in preventing Alzheimer´s disease in

human females. One would predict that estrogens would have a similar protective role in the sexually intact

female dogs; unfortunately too few sexually intact female dogs were available for inclusion in the present

study to test the hypothesis”55

CONCLUSIONS

An objective reading of the veterinary medical literature reveals a complex situation with respect to the longterm

health risks and benefits associated with spay/neuter in dogs. The evidence shows that spay/neuter

correlates with both positive AND adverse health effects in dogs. It also suggests how much we really do

not yet understand about this subject.

On balance, it appears that no compelling case can be made for neutering most male dogs to prevent future

health problems, especially immature male dogs. The number of health problems associated with neutering

may exceed the associated health benefits in most cases.

For female dogs, the situation is more complex. The number of health benefits associated with spaying may

exceed the associated health problems in many (not all) cases. On balance, whether spaying improves the

odds of overall good health or degrades them probably depends on the age of the dog and the relative risk

of various diseases in the different breeds.

The traditional spay/neuter age of six months as well as the modern practice of pediatric spay/neuter appear

to predispose dogs to health risks that could otherwise be avoided by waiting until the dog is physically

mature, or perhaps in the case of many male dogs, foregoing it altogether unless medically necessary.

The balance of long-term health risks and benefits of spay/neuter will vary from one dog to the next. Breed,

age, and gender are variables that must be taken into consideration in conjunction with non-medical factors

for each individual dog. Across-the-board recommendations for all dogs do not appear to be supportable

from find

ings in the veterinary medical literature.

Page 10 of 12

REFERENCES

1 Burrow R, Batchelor D, Cripps P. Complications observed during and after ovariohysterectomy of 142

bitches at a veterinary teaching hospital. Vet Rec. 2005 Dec 24-31;157(26):829-33.

2 Pollari FL, Bonnett BN, Bamsey, SC, Meek, AH, Allen, DG (1996) Postoperative complications of elective

surgeries in dogs and cats determined by examining electronic and medical records. Journal of the

American Veterinary Medical Association 208, 1882-1886

3 Dorn AS, Swist RA. (1977) Complications of canine ovariohysterectomy. Journal of the American Animal

Hospital Association 13, 720-724

4 Pollari FL, Bonnett BN. Evaluation of postoperative complications following elective surgeries of dogs and

cats at private practices using computer records, Can Vet J. 1996 November; 37(11): 672-678.

5 Teske E, Naan EC, van Dijk EM, van Garderen E, Schalken JA. Canine prostate carcinoma:

epidemiological evidence of an increased risk in castrated dogs. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2002 Nov 29;197(1-

2):251-5.

6 Sorenmo KU, Goldschmidt M, Shofer F, Ferrocone J. Immunohistochemical characterization of canine

prostatic carcinoma and correlation with castration status and castration time. Vet Comparative Oncology.

2003 Mar; 1 (1): 48

7 Weaver, AD. Fifteen cases of prostatic carcinoma in the dog. Vet Rec. 1981; 109, 71-75.

8 Cohen D, Reif JS, Brodey RS, et al: Epidemiological analysis of the most prevalent sites and types of

canine neoplasia observed in a veterinary hospital. Cancer Res 34:2859-2868, 1974

9 Theilen GH, Madewell BR. Tumors of the genital system. Part II. In:Theilen GH, Madewell BR, eds.

Veterinary cancer medicine. 2nd ed.Lea and Febinger, 1987:583-600.

10 Glickman LT, Glickman N, Thorpe R. The Golden Retriever Club of America National Health Survey 1998-

1999 http://www.vet.purdue.edu//epi/golden_retriever_final22.pdf

11 Handbook of Small Animal Practice, 3rd ed

12 Hayes HM Jr, Pendergrass TW. Canine testicular tumors: epidemiologic features of 410 dogs. Int J

Cancer 1976 Oct 15;18(4):482-7

13 Ru G, Terracini B, Glickman LT. (1998) Host-related risk factors for canine osteosarcoma. Vet J 1998

Jul;156(1):31-9

14 Cooley DM, Beranek BC, Schlittler DL, Glickman NW, Glickman LT, Waters DJ. Endogenous gonadal

hormone exposure and bone sarcoma risk. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2002 Nov;11(11):1434-40.

15 Moe L. Population-based incidence of mammary tumours in some dog breeds. J of Reproduction and

Fertility Supplment 57, 439-443.

16 Ferguson HR; Vet Clinics of N Amer: Small Animal Practice; Vol 15, No 3, May 1985

17 MacEwen EG, Patnaik AK, Harvey HJ Estrogen receptors in canine mammary tumors. Cancer Res., 42:

2255-2259, 1982.

18 Schneider, R, Dorn, CR, Taylor, DON. Factors Influencing Canine Mammary Cancer Development and

Postsurgical Survival. J Natl Cancer Institute, Vol 43, No 6, Dec. 1969

19 Feinleib M: Breast cancer and artificial menopause: A cohort study. J Nat Cancer Inst 41: 315-329, 1968.

20 Dorn CR and Schneider R. Inbreeding and canine mammary cancer. A retrospective study. J Natl Cancer

Inst. 57: 545-548, 1976.

21 Brodey RS: Canine and feline neoplasia. Adv Vet Sci Comp Med 14:309-354, 1970

22 Hayes A, Harvey H J: Treatment of metastatic granulosa cell tumor in a dog. J Am Vet Med Assoc

174:1304-1306, 1979

Page 11 of 12

23 Norris AM, Laing EJ, Valli VE, Withrow SJ. J Vet Intern Med 1992 May; 6(3):145-53

24 Prymak C, McKee LJ, Goldschmidt MH, Glickman LT. Epidemiologic, clinical, pathologic, and prognostic

characteristics of splenic hemangiosarcoma and splenic hematoma in dogs: 217 cases (1985). J Am Vet

Med Assoc 1988 Sep; 193(6):706-12

25 Ware WA, Hopper, DL. Cardiac Tumors in Dogs: 1982-1995. J Vet Intern Med 1999;13:95-103.

26 Panciera DL. Hypothyroidism in dogs: 66 cases (1987-1992). J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1994 Mar

1;204(5):761-7

27 Panciera DL. Canine hypothyroidism. Part I. Clinical findings and control of thyroid hormone secretion and

metabolism. Compend Contin Pract Vet 1990: 12: 689-701.

28 Glickman LT, Glickman N, Raghaven M, The Akita Club of America National Health Survey 2000-2001.

http://www.vet.purdue.edu/epi/akita_final_2.pdf

29 Glickman LT, HogenEsch H, Raghavan M, Edinboro C, Scott-Moncrieff C. Final Report to the Hayward

Foundation and The Great Dane Health Foundation of a Study Titled Vaccinosis in Great Danes. 1 Jan

2004. http://www.vet.purdue.edu/epi/great_dane_vaccinosis_fullreport_jan04.pdf

30 Edney AT, Smith PM. Study of obesity in dogs visiting veterinary practices in the United Kingdom. .Vet

Rec. 1986 Apr 5;118(14):391-6.

31 McGreevy PD, Thomson PC, Pride C, Fawcett A, Grassi T, Jones B. Prevalence of obesity in dogs

examined by Australian veterinary practices and the risk factors involved. Vet Rec. 2005 May

28;156(22):695-702.

32 Lund EM, Armstrong PJ, Kirk, CA, Klausner, JS. Prevalence and Risk Factors for Obesity in Adult Dogs

from Private US Veterinary Practices. Intern J Appl Res Vet Med o Vol. 4, No. 2, 2006.

33 Marmor M, Willeberg P, Glickman LT, Priester WA, Cypess RH, Hurvitz AI. Epizootiologic patterns of

diabetes mellitus in dogs Am J Vet Res. 1982 Mar;43(3):465-70. ..

34 Moore GE, Guptill LF, Ward MP, Glickman NW, Faunt KF, Lewis HB, Glickman LT. Adverse events

diagnosed within three days of vaccine administration in dogs. JAVMA Vol 227, No 7, Oct 1, 2005

35 Thrusfield MV, Holt PE, Muirhead RH. Acquired urinary incontinence in bitches: its incidence and

relationship to neutering practices.. J Small Anim Pract. 1998. Dec;39(12):559-66.

36 Stocklin-Gautschi NM, Hassig M, Reichler IM, Hubler M, Arnold S. The relationship of urinary

incontinence to early spaying in bitches. J Reprod Fertil Suppl. 2001;57:233-6…

37 Arnold S, Arnold P, Hubler M, Casal M, and Rüsch P. Urinary Incontinence in spayed bitches: prevalence

and breed disposition. European Journal of Campanion Animal Practice. 131, 259-263.

38 Thrusfield MV 1985 Association between urinary incontinence and spaying in bitches Vet Rec 116 695

39 Richter KP, Ling V. Clinical response and urethral pressure profile changes after phenypropanolamine in

dogs with primary sphincter incompetence. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1985: 187: 605-611.

40 Holt PE. Urinary incontinence in dogs and cats. Vet Rec 1990: 127: 347-350.

41 Seguin MA, Vaden SL, Altier C, Stone E, Levine JF (2003) Persistent Urinary Tract Infections and

Reinfections in 100 Dogs (1989-1999). Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine: Vol. 17, No. 5 pp. 622-631.

42 Spain CV, Scarlett JM, Houpt KA. Long-term risks and benefits of early-age gonadectomy in dogs.

JAVMA 2004;224:380-387.

43 Verstegen-Onclin K, Verstegen J. Non-reproductive Effects of Spaying and Neutering: Effects on the

Urogenital System. Proceedings of the Third International Symposium on Non-Surgical

Contraceptive Methods for Pet Population Control

http://www.acc-d.org/2006%20Symposium%20Docs/Session%20I.pdf

44 Hagman R: New aspects of canine pyometra. Doctoral thesis, Swedish University of Agricultural

Sciences, Uppsala, 2004.

OH NO!!! Just one?!

Depending on your breed, that may be a familiar cry of woe. Cryptorchidism is one of those quiet defects lingering just under the surface of many breeds. Certainly there are other more devastating defects that interfere with a dog enjoying life even as a pet such as hip dysplasia or epilepsy. Still, the lack of two descended testicles can destroy your hopes for a stunning male dog in the breed ring or for use at stud.

So how does this happen? It helps to understand the development of a normal male first. The kidneys and the testicles develop very closely together in the canine embryo. In fact, an intermediate stage of kidney development, the mesonephron regresses to become the testicle. Both the kidneys and the testicles are technically outside of the abdominal cavity as they are behind a mesentery that puts them “retroperitoneal” or behind the peritoneum which lines the abdomen. That fact becomes important later during descent into the scrotum.

Since the testicles develop way up by the kidneys, that means they have a long way to travel to reach the scrotal sac. The right kidney is slightly more cranial or towards the head in location which means the right testicle is also slightly more cranial. In fact, it is felt that the right testicle is more often the one retained, or left inside the body, due to the longer journey it has. Once descended into the scrotum, the left testicle tends to be located slightly higher and behind the right one.

The testicles are pulled down into the scrotal sac by connective tissue type ligaments called the gubernaculums. This cord regresses towards the scrotal sac, pulling the testicle along with it. Each testicle travels independently on its own side. Eventually the gubernaculums will exist only as a scar that fixes the testicle into its side of the scrotal sac. This action seems to be under the influence of testosterone – but simply giving testosterone injections will not help a wayward testicle.

The scrotal sac itself is continuous with the abdominal cavity so when the testicles enter the scrotum through the inguinal canal (an opening in the muscles that allows the testicles to leave the main body cavity and enter the scrotum) they push the abdominal membranes with them. This can lead to inguinal hernias in dogs whose inguinal canals do not close by 6 months of age or whose canals are quite large to begin with. In these cases, intestines slip into the opening along with the testicles or in place of them.

{jb_left45}Terminology

Cryptorchid – a dog who does not have two testicles in the scrotum

Unilateral cryptorchid – the more common condition in which a dog only has one testicle in the scrotum with the other anywhere from along the penis to inside the abdomen

Bilateral cryptorchid – a dog with no testicles descended into the scrotum – less common than a unilateral cryptorchid

Monorchid – a dog who truly only has one testicle formed – which may be located in the scrotum or in the abdomen – not very common

Anorchidism – a rare condition where there are no testicles developed – externally or internally{/jb_left45}

Normally the testicles have both descended into the scrotum by six to ten days after whelping. They are quite small then and not easy to palpate. Since the inguinal canal is still open and the testicles quite small, they may be pulled back up into the body by the cremaster muscle. Generally both testicles should be palpable and well seated in the scrotum by six to eight weeks of age. Some people will allow up to six months for descent of the testicles but delayed descent such as those cases is possibly a degree of cryptorchidism and associated genetically. Genetic studies in mice have shown a correlation between late descent and eventual cryptorchidism. By six months, the inguinal canal has generally closed down enough to prevent a testicle from moving down or up.

A cryptorchid testicle gets waylaid some where on this journey. It may make it almost to the scrotal sac and end up trapped on the wrong side of the inguinal canal or it may still be way up by the kidney. Surgical removal is always recommended as these testicles are prone to developing cancers and may also twist or torse.

Looking at historical lists of breeds predisposed to cryptorchidism, certain breeds appear on virtually every list. These include: Toy and Miniature Poodles, Pomeranians, Yorkshire Terriers, Dachshunds, Miniature Schnauzers, Maltese, Chihuahuas, Pekingese, Cairn Terriers and Shetland Sheepdogs. Among larger breeds, English Bulldogs, Boxers and Old English Sheepdogs appear. However, virtually every breed and mixed breeds have experienced at least some cryptorchidism. Current studies include Siberian Huskies, Belgian Sheepdogs and Border Collies. A very informal survey (done with breeders on three small email lists) by me came up with 380 male puppies with 42 cryptorchids, including eight bilateral cyrptorchids. The latest descent was 11 ½ months of age. Eleven breeds and five groups were included. It should also be noted that within a breed, there may be lines that are more or less prone to having cryptorchids. In general, incidence may range from 1.2 percent to 10 percent.

Dr Max Rothschild PhD, Distinguished Professor of Iowa State University is working on the genetic aspects of cryptorchidism through a grant from the AKC´s Canine Health Foundation. His work is centered around Siberian Huskies with a 14 percent rate of cryptorchidism on their latest health survey. So even breeds not on the standard list can have a fair amount of cryptorchidism present in the breed population.

Dr. Vicki Meyers-Wallen VMD, PhD, Dipl. ACT is a researcher at Cornell University´s Baker Institute for Animal Health. As she points out, “The risk can become higher or lower in a breed over time, depending on the selection that breeders have exercised (or failed to exercise) to limit or eliminate this trait.” She takes the tough stand that if both testicles aren´t where they should be – firmly in the scrotal sac – by six weeks of age, then the dog should not be considered normal.

Cryptorchidism seems to be influenced by at least three genes but works out in many pedigrees as a simple autosomal recessive that is sex limited. That means both males and females can be carriers, so stud dog and brood bitch both contribute, but in this case, only males show the defect. However, Dr. Rothschild states, “This seems to be a complex trait controlled by multiple genes and is caused not only by genetic components but also by epigenetic and environmental factors.”

Geneticists recommend a minimum of 40 puppies produced as evidence that a dog or bitch does not carry the gene(s) for cyrptorchidism. (And certainly the choice of stud or dam with their own genetic makeup would affect whether any cryptorchid puppies show up.) Most bitches will not produce that many puppies over their lifetimes so their status remains more or less unknown. A male who is a carrier will appear normal (two testicles present in the scrotum) but will pass the defect on to half his offspring. A male who is homozygous for the trait will be a unilateral or bilateral cryptorchid. It is not known how modifier genes affect the unilateral versus bilateral status or the timing of descent. Certainly cryptorchidism is not the simple inherited trait we once thought it was. Still, if a cryptorchid puppy shows up in a litter, it can be assumed that the stud dog is a carrier of this trait and the dam is at least a carrier if not homozygous for the trait. So far no fertility problems have been identified in carrier or homozygous bitches or obvious defects to help identify them before breeding.

So how do researchers go about tackling this problem? Dr. Rothschild is looking at candidate genes from other species. This means looking at a species where

genes that are associated with cryptorchidism have been identified and then checking out those same areas on the canine genome. When reading genetic research, you will see SNPS mentioned. These are single nucleotide polymorphisms. To go back to your high school biology, a SNP might have the nucleotide C for cytosine in a certain location on one dog´s gene. Another dog might have a T for thymine in that same location. If that is a gene suspected of influencing cryptorchidism, that SNP, or change in nucleotide, might be significant.

In Dr. Rothschild´s research, he can compare the genome of a “normal” male Siberian Husky to the genome of a cryptorchid dog to see where there are changes in the genetic code. He is currently looking at 75 pairs of Siberian Husky genes to search for a key to this trait.

Dr. Meyers-Wallen has followed a similar path. She started out by checking genes associated with human cryptorchidism in the hopes that there might be a similar causal relationship in dogs. “We did not find mutations in those genes in affected dogs, but the mutations that cause cryptorchidism in humans have not been identified in the majority (over 90%) of the human patients either. Clearly we need to identify canine mutations by other means, rather than waiting for discoveries in human medicine to help us with the dog.”

Using two breeds, Border Collies and Belgian Sheepdogs, Dr. Meyers-Wallen, in collaboration with Dr. Hannes Lohi, has identified a chromosomal region of interest that is likely to contain sequence differences in the gene that should be associated with cryptorchidism. They are looking further to try and identify the exact mutation in that region. Between them, these two research projects have made considerable progress in determining what genes are not involved in canine cryptorchidism. That makes the hunt for the right gene easier.

So while we wait for a genetic test to identify carriers in the case of stud dogs and carriers or homozygous individuals in the case of bitches, what are we to do? For many breeds, if the standard livestock recommendation of not breeding any siblings or the parents of affected dogs again was carried out, we would lose a huge part of our genetic diversity and probably end up with more serious health problems. At least cryptorchid dogs can be neutered and placed as wonderful pets.

Still, it makes sense to never breed a cryptorchid dog as we know he is affected. And yes, cryptorchids are fertile as the one testicle outside the body can produce viable sperm. Certainly we can look at pedigrees and work out the likelihood of producing a cryptorchid puppy in many cases. For example, say your bitch is from a litter with a cryptorchid brother. You are looking at two prospective stud dogs. One is from a litter with two cryptorchid brothers. The other is from a litter with seven males, all intact. It is still no guarantee, but your best bet is the male with no known cryptorchid siblings.

Once a genetic test is available, it will be a major help in planning breeding and knowing early on if a puppy would be a good candidate as a show or breeding dog. It is very likely that many bitches will be affected or carriers as there is currently no way to screen for them. But, if breedings are planned carefully and affected offspring can be identified we can gradually breed away from this fault.

As breeders we can help by supporting research projects such as the two mentioned here. Both money and samples from related and affected dogs can be important for a research project. And who knows, one of your dogs could provide the answer to this genetic defect!

For Dogs in Review

Deb M. Eldredge, DVM

How To Raise A Happy, Healthy, Confident Puppy

by Faye Strauss

It is very important you be consistent, patient, and thoughtful, just as you would be with a child. Building confidence, so the puppy understands “everybody loves me,” will be the basis on which to develop a secure, dependable adult.

The following are some Guidelines for raising your puppy :

- Puppies don´t make mistakes; people do. When the puppy misbehaves you go to the puppy , never correct the puppy when he comes to you. Correct gently but firmly, and follow with praise. The `come´ command should always be the happiest sound a puppy can hear. Never call your puppy in anger.

- Puppies can develop an extensive vocabulary if you verbalize an activity when the puppy does it with consistency. Examples are: `Who´s hungry?´ `Water´, `outside´, `go potty´, `off´ (the sofa or you), `go to bed´, `car´, `go for walk´, `cookie´, get `your toy´, `quiet´, `guard´ and `find (an object or person)´.

- Never hit a puppy, especially in the face or head. Besides being cruel this will cause “hand shyness”. Always be aware that a teething puppy will bite almost anything to relieve the pain, including your hand, your favourite shoe or the furniture. We have found that a Nylabone soaked in chicken broth and put in the freezer relieves the puppy´s discomfort. Be careful when correcting a teething, nippy puppy; their sharp teeth can really hurt, but you must be aware they are not displaying aggression.

- Never pick the puppy up under the shoulders (as you would a small child). Always support his rear end with one hand and with the other hand firmly in place under the chest, between his front legs. Do not let children pick up the puppy; they will not do it properly. Most Veterinarians know how to handle Doberman puppies.

- Don´t hold balls, food or other bait up in the air so that the puppy has to jump up to get them. This may look cute to you but upon landing the puppy may injure his shoulders, knees, or rear legs. You don’t want to encourage this trait for training purposes either because eventually you won´t want a 90 pound dog jumping up or jumping on you for the ball or his treats. I don´t see anything wrong with allowing jumping up as a puppy to some extent just so long as it isn´t in excess. The puppy will be doing this on his own in play anyway. You can even use this natural trait of jumping to teach the puppy not to jump by saying “no jump” or “off” and etc.

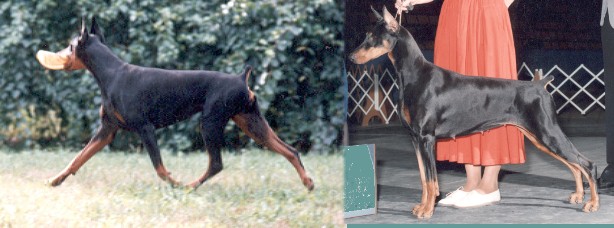

- Looking to the future, some day your puppy may be in the show ring. Starting as young as possible, teach him to “bait.” When you give him a treat have him standing , not sitting, with ears forward, in eager anticipation. Teach him a word for watching the bait or object. (example “watch”)

- Be careful with your puppy when he climbs up and especially down stairs. Puppies can do this if they are allowed to go up or down on their own power as long as there are only two or three stairs but if they appear to have a lot of difficulty then we recommend that you carry the puppy “down” stairs until around three months of age. We use their climbing up and down stairs to teach “up-up-up” and “down-down-down.”

- Get the puppy used to having his teeth examined. When you open the mouth say “open”. Encourage other people to “go over” his mouth. If you make a mouth examination part of the daily routine it won´t be a traumatic experience when the judge examines his dentition. When the puppy is teething however forego this examination.

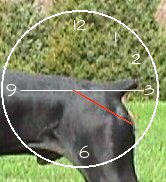

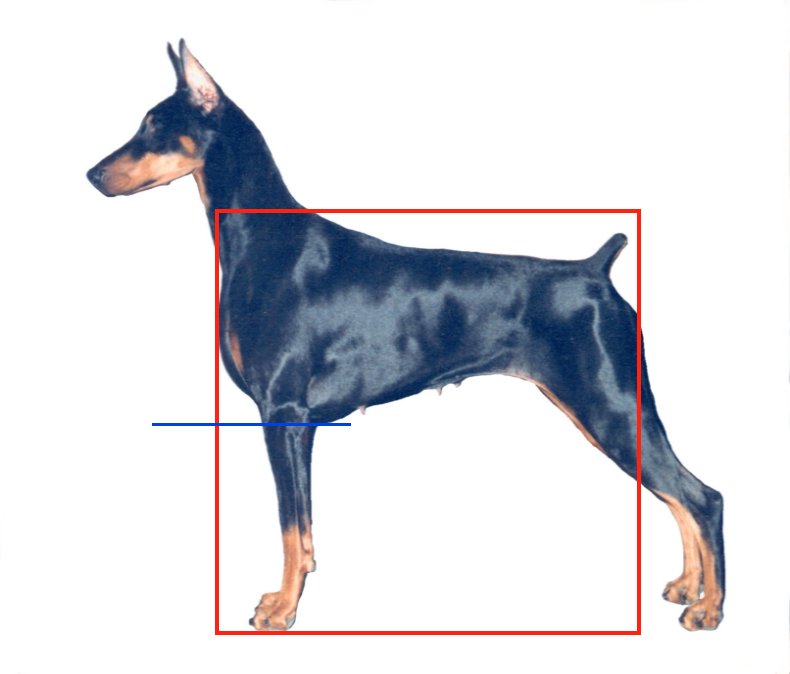

- Surfaces should provide traction. Don’t let the puppy play on slippery surfaces such as kitchen tile and/or linoleum for extended periods of time. A puppy who continually runs or struggles to get up from slippery surfaces could become cow hocked. (i.e. – the back feet are forced outward and the knees inward as the puppy tries to gain footing). If you have a problem with a surface in your home, buy some area or scatter rugs with a firm backing so that the puppy won´t slide.

- How a puppy is leash trained is very important in the process of developing a calm, responsive dog at the end of the lead. We believe in giving the puppy a hassle free introduction to the lead simply by going with him in any direction he chooses. You go where he goes with no stress or tugs on the leash. You can use the words “let’s go” for leash training.