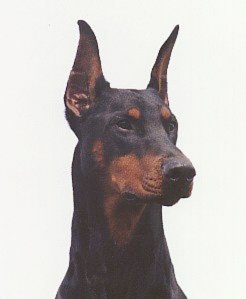

Long and dry, resembling a blunt wedge in both frontal and profile views. When seen from the front, the head widens gradually toward the base of the ears in a practically unbroken line. Eyes almond shaped, moderately deep set, with vigorous, energetic expression. Iris, of uniform color, ranging from medium to darkest brown in black dogs; in reds, blues, and fawns the color of the iris blends with that of the markings, the darkest shade being preferable in every case. Ears normally cropped and carried erect. The upper attachment of the ear when held erect, is on a level with the top of the skull. Top of skull flat, turning with slight stop to bridge of muzzle, with muzzle line extending parallel to top line of skull. Cheeks flat and muscular. Nose solid black on black dogs, dark brown on red ones, dark gray on blue ones, dark tan on fawns. Lips lying close to the jaws. Jaws full and powerful, well filled under the eyes.

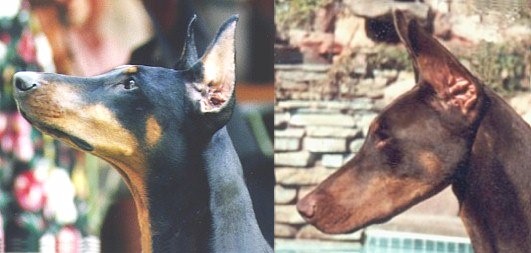

When judging the head, examination requires three views.

- Full front looking down on the head

- Full profile

- A ½ front view to assess the proportion of the head to the body.

Long and dry, resembling a blunt wedge in both frontal and profile views. When seen from the front, the head widens gradually toward the base of the ears in practically an unbroken line – the muzzle and top of the head appear to be the same length (ratio of 1:1). Jaws full and powerful, well filled under the eyes, which means when you put your hands on the side of the muzzle, there should be a “face” filling your hands. If not, the dog doesn’t have enough “fill” under the eyes. Fill under the eye is important for a correct head because the jaws must be full and powerful to hold the 42 strongly developed and correctly placed teeth.

From the side you should have the same impression of the head as from the front. This means the dog should have some underjaw, not just a chin with a lip over it to give the impression of a blunt wedge. Good underjaw can be seen from the front and profile view. The side view will show the flat skull with the line of the skull parallel to the line of the muzzle. The stop is `slight’, thus the ideal amount is more than a Collie and less than a Great Dane.

The head should be correctly proportioned for the body. The Doberman is not a “head” breed, so the basic question is whether the head fits the individual dog. That’s why it’s important to observe the head from different views.

|

|

|

Good underjaw can be seen from the profile view |

Eyes almond shaped and moderately deep set, with vigorous, energetic expression – Round eyes give the dog a softer expression as does a shallower set eye. Eyes are moderately deep set, which means “middle” – not too deep and not too shallow. Because of the original purpose of the breed, a dark eye is much more desired. Black dogs with yellow/gold eyes, red dogs with green or yellow eyes, blue dogs with gold or gray eyes and fawns with blue or gold eyes are not desired, darker eyes are preferred. The standard states medium to dark brown eyes on a black dog, so are black eyes a deviation of the standard? If you notice any prominence to the eyes (color, shape, depth), it is most likely a deviation.

Ears normally cropped and carried erect – The original 1923 standard stated that ears were “well placed and clipped to a point”. Today’s standard is telling us that ears are either “usually cropped” or “cropped in a normal fashion”. What is a normal ear crop and should we now base our opinion of the dog’s ears on what someone has unnaturally done to our dogs? Obviously where the ears are placed on the head is more important than the crop. A bad ear crop can pull an ear down so they wing out, literally pull an ear down so it won’t stand erect, or distort the shape of the head altogether. Most ears are cropped very long and it’s difficult for the dogs to keep them up. Do NOT expect a dog to carry ears erect while gaiting, unless they are alert to something as they are moving. An exceptionally short crop can give the appearance of a shorter neck, shorter and wider muzzle. Since the standard states that ears are “normally” cropped, is an uncropped ear is a deviation of the standard? Rather than harshly penalize a dog with uncropped ears, determine if the ears are in proportion to the head and the placement is correct.

A short ear crop

|

A long ear crop

|

Uncropped

|

|

|

|

Judge the dog on the ear placement and carriage, not the (man made) crop or lack there of. The dog on the left and middle are the same dog. The natural eared dog has a cowlick. A short ear crop or natural (uncropped) ear can give the illusion of a wider head, shorter muzzle and shorter neck.

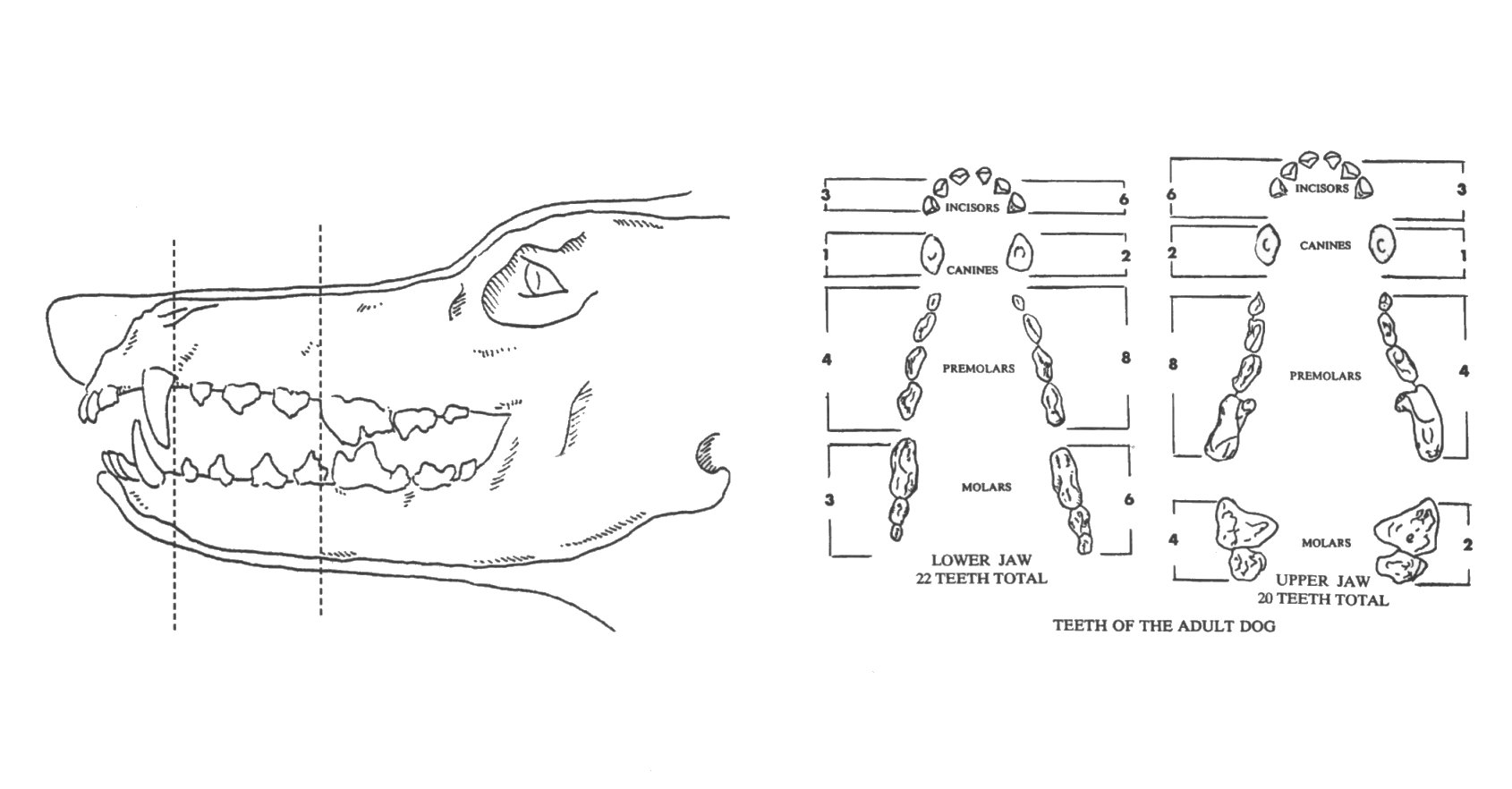

Teeth strongly developed and white. Lower incisors upright and touching inside of upper incisors- a true scissors bite. 42 correctly placed teeth, 22 in the lower, 20 in the upper jaw. Distemper teeth shall not be penalized. Disqualifying Faults: Overshot more than 3/16 of an inch. Undershot more than 1/8 of an inch. Four or more missing teeth.

Teeth strongly developed and white. Lower incisors upright and touching inside of upper incisors – a true scissors bite. 42 correctly placed teeth, 22 in the lower, 20 in the upper jaw. Distemper teeth shall not be penalized. Disqualifying Faults: Overshot more than 3/16 of an inch. Undershot more than 1/8 of an inch. Four or more missing teeth.

There is a purpose for such emphasis on this strong head – to hold the strongly developed (good size

d) teeth. Since three of the four disqualifications are in the mouth, it is important know what a correct mouth looks like and be accurate when counting teeth. The standard assumes that you know the names of all the teeth. Correctly placed teeth lets you know that a missing tooth replaced by an extra tooth is a deviation from the standard and must be considered as a fault. You may have 42 correctly placed teeth, and extra teeth in the spaces – consider this as a deviation from the required “correctly placed” teeth. It is not the same as missing teeth, which lead to a disqualification, but a deviation and should be considered to the extent that they affect occlusion and the number of extra teeth. To say that a dog with 3 extra teeth is the same as having a dog with 3 missing teeth is incorrect. The standard is clear that 4 missing teeth is a disqualification, it does NOT state that 4 extra teeth is a disqualification; but a deviation.

The three disqualifications in the mouth — the requirement of a true scissors bite– overshot more than 3/16″ and undershot more than 1/8″ make up two disqualifications. The standard is clearly stating what a scissors bite is. No, we have no tool to measure the exact distance that makes up the over or undershot bite, but the standard is clear as to how far over or undershot we should tolerate – how close the `scissors’ should be. Without these `measures’ a “true scissors” bite is left to interpretation. Four or more missing teeth is the third disqualification in the mouth, so it is important to know how to count teeth and identify them.

The only way to check for missing teeth is to OPEN THE MOUTH.

|

|

A quick lesson in counting teeth:

The standard specifies the number of teeth, the correct placing of the teeth and by implication, occlusion, so be sure to check for all of these. The easiest way is to count teeth is in groups. On the top there are two groups of 3 and 3 (two groups of three teeth on each side) and in the lower jaw two groups of 4 and 3. The only way to check for missing teeth is to OPEN THE MOUTH. There is no way to determine if the back molars are present with the mouth closed. Overshot and undershot are deviations from the scissors bite. They are to be considered a fault the same as missing teeth. While a level bite is not correct, it is only a deviation from what is correct, and should be considered just as any other deviation, over faults that may be more important to the overall dog. Occlusion should be checked from the side as well as the front of the mouth. The only way to check for missing teeth is to OPEN THE MOUTH.

Click the following links to read more articles in the “Dobermans in Detail” series:

by Linka Krukar submitted by Marj Brooks