The angulation of the hindquarters balances that of the forequarters. Hip Bone falls away from spinal column at an angle of about 30 degrees, producing a slightly rounded, well filled-out croup. Upper Shanks at right angles to the hip bones, are long, wide, and well muscled on both sides of thigh, with clearly defined stifles. Upper and lower shanks are of equal length. While the dog is at rest, hock to heel is perpendicular to the ground. Viewed from the rear, the legs are straight, parallel to each other, and wide enough apart to fit in with a properly built body. Dewclaws, if any are generally removed. Cat feet as on front legs, turning neither in nor out.

Again the standard is very specific; balance is called for between the front and the rear of the dog. The rear assembly mirrors the front assembly in its requirement for angles and balance, thus it is imperative that the rear is in balance with the front! Do not judge the rear independently from the front! The hip bone falls away from the spinal column at such an angle (30 degrees) to produce the slightly rounded, well filled out croup. When the hip bone appears to follow the line of the back when viewed from the side instead of being angled at 30 degrees, the croup appears flat, with the accompanying high set tail that is INCORRECT! Because handling can distort rears, it is very important to judge the angle of the croup when the dog is in motion or standing on its own. When the dog with the correct angulation moves, he will have a powerful rear that propels him forward without wasted energy of the high kick up behind. When the dog with the flatter croup moves, the tail will be carried too high (remember slightly above the horizontal — out rather than up) and the rear legs will be moving up and behind (in wasted motion) rather than under the dog “digging” into the ground to propel him forward. Right angles are called for between the long, wide, and well muscled upper shanks and hip bones, with clearly defined stifles. There are many straight stifles to go with the straight front assemblies. These straighter stifles are usually accompanied by a long hock. There are also many long stifles that are out of balance with the front, so the dog’s rear legs are too far behind the rear assembly — the dog “stands over a lot of ground” like a German Shepherd. Keep in mind that the standard requires equal length of upper and lower shanks. Because of the specific angles the standard requires, without specifically mentioning the word “hock”, it is clear that it must be short. The shorter the hock, the stronger the joint, thus the long hock is another way of compensating for the less than desired short, straight stifle. This is usually evident when you watch the dog move and the rear “follows the front” instead of providing power to propel the dog forward.

The standard specifically states a “clearly defined stifle”, but does not call for a “well turned stifle”. The reasons for these requirements are partly functional and partly in genetic problems of the breed. In the early mixtures, many Dobermans appeared with longer rear legs than front legs. The judge that “prefers” the longer legged rear with the sweeping turn of stifle may be augmenting the problem! Judge to the standard! Remember when judging the rear — begin with the hip, then proportions, then the degrees of angulation as compared to the front.

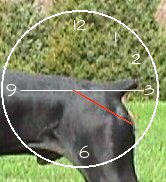

The photo shows correct tail placement (slightly above the horizontal) The red line shows that the hip bone falls away from the spinal column at a 30 degree angle to produce the slightly rounded, well filled out croup

|

|

Click the following links to read more articles in the “Dobermans in Detail” series:

by Linka Krukar submitted by Marj Brooks