Breeder/Exhibitor Ed, Breeding/Genetics

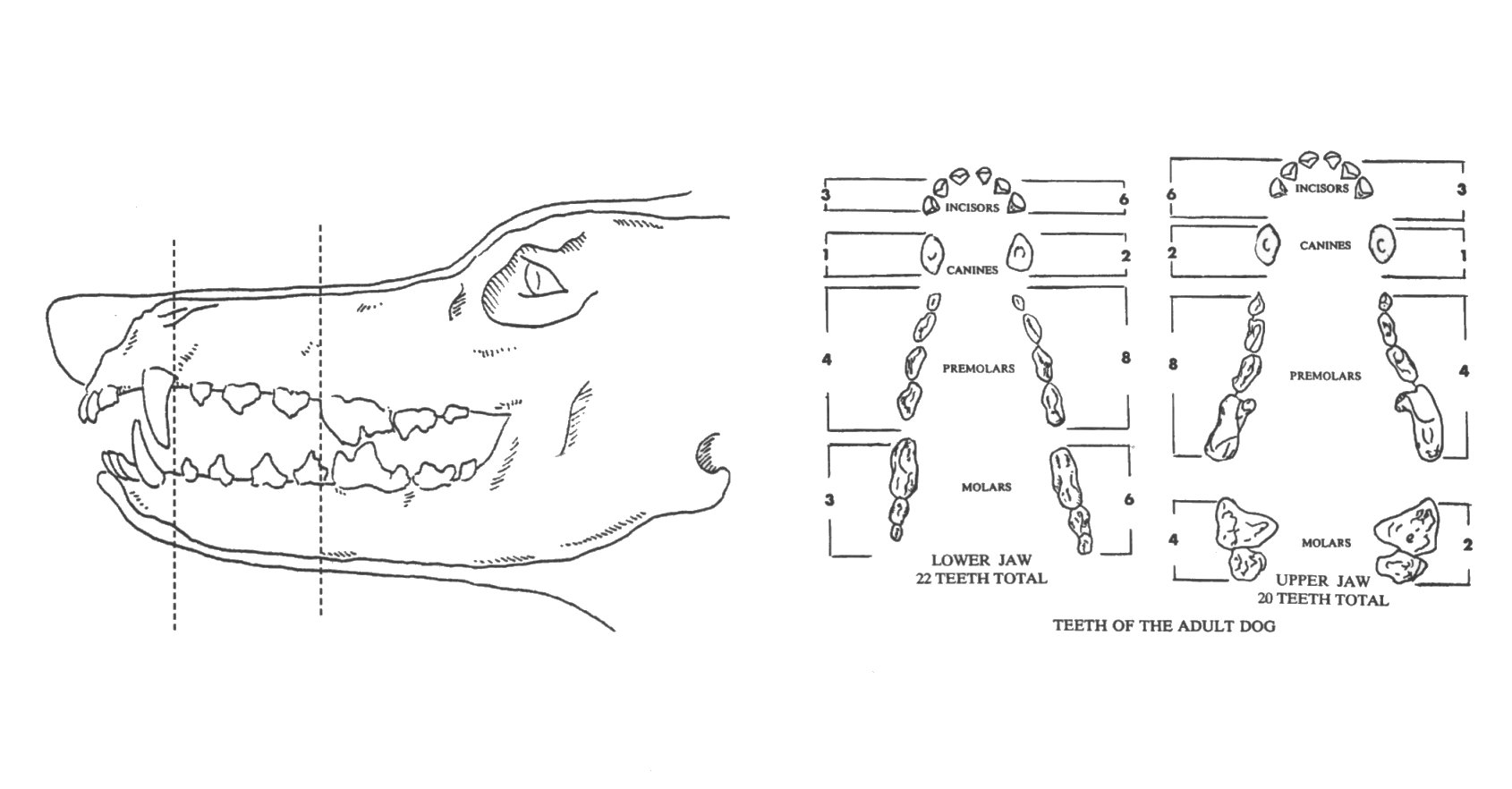

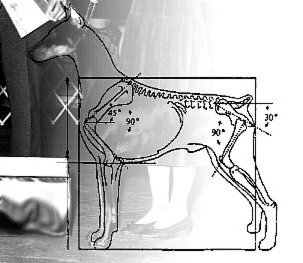

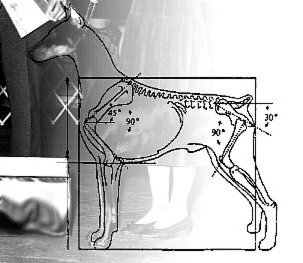

Shoulder Blade sloping forward and downward at a 45-degree angle to the ground meets the upper arm at an angle of 90 degrees. Length of shoulder blade and upper arm are equal. Height from elbow to withers approximately equals height from ground to elbow. Legs seen from front and side, perfectly straight and parallel to each other from elbow to pastern; muscled and sinewy, with heavy bone. In normal pose and when gaiting, the elbows lie close to the brisket. Pasterns firm and almost perpendicular to the ground. Dewclaws may be removed. Feet well arched, compact, and catlike, turning neither in nor out.

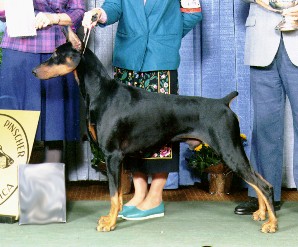

Shoulder blade sloping forward and downward at a 45 degree angle – Although this angulation is impossible to get, it indicates the importance placed on the angulation of the shoulder. This angulation allows for the beautiful, smooth flow of the neck into the shoulder. The Doberman standard repeatedly stresses the balance of all the parts – length of shoulder blade to upper arm are equal; the height from elbow to withers approximately equals height from ground to elbow. Many Dobermans have the entire shoulder assembly pushed forward with a short upper arm. The better the layback of shoulder, the longer and smoother the neck will appear (it should still be in proportion to everything else). Again, the depth of body should be equal to the length of leg. This does NOT allow for the high stationed dog that many find so appealing. Applying the standard takes precedence over personal preference. When the proportions are correct, the dog appears shorter on leg and longer in body. The dog that has more length of leg and less depth of body generally may give the illusion of being square, but in reality, is really too short backed.

The legs are straight, which means they don’t have the curves of the achondroplastic breeds. While the correct pastern appears almost straight, there is a “slight”, although very slight bend in the pastern. A pastern that is too straight or long cannot absorb the impact of gaiting. It is NOT correct!

Heavy bone does not mean big boned, it refers to a round bone versus an oblong bone, which has the appearance of “light” bone. The 1948 standard stated “legs… muscled and sinewy with round, heavy bone”. In normal pose and when gaiting, the elbows lie close to the brisket–look at the dog from the back and you should be able to see the elbow fit tightly into the brisket. There should be no air space between the elbow and body. If you can see through the area or it looks like you can get a hand in there, the lay on is not correct and the dog will probably stand wide, move wide or toe in and not gait properly.

Feet well arched, compact and catlike, turning neither in nor out – a dog with large or flat feet is like a car with flat tires. Well arched feet that are held strongly together indicate tight tendons for good shock absorption. Long toes are associated with longer tendons and usually weaker (or more let down) pasterns. This will be evident when the dog moves. Toes should be short and tight. Large feet will not only have the appearance of sloppy movement, but cannot cushion or absorb as well as the short, tight toes. Judge the “turning neither in nor out” when the dog is moving. Dogs can be trained to stand properly, but they will move naturally.

|

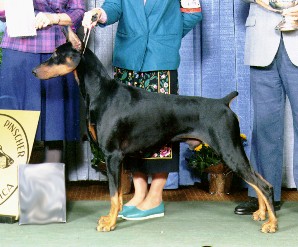

Two examples of cat feet.

|

|

|

|

Left is a young dog and right is an adult

|

Click the following links to read more articles in the “Dobermans in Detail” series:

Size, proportion &substance

Head

Neck Topline and Body

Forequarters

Hindquarters

Coat

Gait

Temperament

Conclusion: test yourself

by Linka Krukar submitted by Marj Brooks

Breeder/Exhibitor Ed, Breeding/Genetics

Neck proudly carried, well muscled and dry. Well arched, with nape of neck widening gradually toward body. Length of neck proportioned to body and head. Withers pronounced and forming the highest point of the body. Back short, firm, of sufficient width, and muscular at the loins, extending in a straight line from withers to the slightly rounded croup.

Chest broad with forechest well defined. Ribs well sprung from the spine, but flattened in lower end to permit elbow clearance. Brisket reaching deep to the elbow. Belly well tucked up, extending in a curved line from the brisket. Loins wide and muscled. Hips broad and in proportion to body, breadth of hips being approximately equal to breadth of body at rib cage and shoulders.

Tail docked at approximately second joint, appears to be a continuation of the spine, and is carried only slightly above the horizontal when the dog is alert.

Neck proudly carried, well muscled and dry – The neck is proportional in length and width to the head and body, tapering gently from the body to the head. It appears almost as wide as the body at the body, tapering gracefully but powerfully to the head. The muscle that runs from behind the ear, down the neck, down the front and attaches itself around the upper arm, helps pull the upper arm forward while the dog is gaiting, thus assisting in the reach of the dog. Again, the length of the neck should be in proportion to the body and head. A short neck reduces reach and a neck that is too long stretches the muscle making it weaker, so the dog has to struggle more for efficient gaiting and balance. The neck should widen gradually toward the body- it should not be “skinny” or “thick” and have a natural arch (not the one the handler molds into the dog). The withers form the highest point of the body. All measurements are proportional to the height at the withers; all parts are in proportion to the body.

Back is short, firm – If the back is too short, the dog is out of balance and can’t move out of it’s own way, and usually compensates by over-striding or over-reaching. These dogs compensate in several ways; some may have longer, more sweeping stifles like a German Shepherd or Weimaraner, and some may have straighter stifles with long hocks. If the back is too long, the entire topline can sag or bounce when the dog moves. The problem with the requirement of a square body with a short back, plus the additional 90 degree angulation at each end of the dog, is that there is no way the dog can get out of it’s own way unless it’s in complete balance!

Back of sufficient width, and muscular at the loins, extending in a straight line from withers to the slightly rounded croup– when looking down on the dog, there should be an “hour glass” shape and not a “tube”. The shoulders, ribs, and the rear should be the same width. The slightly rounded croup may not look as pleasing as the flat croup, but it is correct. In this case the “back” is referring to the topline and should be in a straight line from the withers to the correct croup. This straight line is based on a correctly built dog and will be `level’ rather than `sloping’ if the dog has correct structure. The dramatically sloping topline is a clear indication that proper balance is not present because the angles at each end don’t match. The dog with a level to slightly sloping topline has correct balance. The correct topline fits a dog whose legs are under him, ready to move in any direction. The dog’s major weight is balanced on his front feet, rear legs squarely set, ready to move forward or to the side. The extremely sloping topline fits a dog standing, but not ready for movement. The topline will slope if the shoulders are straighter or if the dog has too much turn of stifle, which will lower the rear.

Chest is broad with the forechest well defined – meaning that the forechest has “definite and distinct lines or features,” not necessarily well endowed! The original 1923 standard stated “chest arched and reaching deep to the elbow.” Moderation is another key to a Doberman. A Doberman is not supposed to have excessive forechest, but enough to indicates there is a forechest; showing the precise outline of it. A large forechest doesn’t necessarily mean a good front.

Brisket reaching deep to the elbow – The depth is important because a larger body cavity allows more room for the organs. The underline is formed by the 1) deep brisket which flows back through 2) the ribs that extend far back in the body that gradually shorten to form 3) the tuck up flowing into the short loin. These are all important to a correct body and the impression of power and endurance. Underlines can have as many problems as toplines! Belly well tucked up does not mean a wasp waist or herring gut. The tuck up can be too extreme or the reverse of no, or too little tuck up giving the dog a `flat’ underline that appears straight across. The underline should gradually angle up to allow the hindquarters to reach under the dog comfortably while the dog is gaiting.

Loins wide and muscled, but not as wide as the rear. The rear should not be narrow, but broad and well muscled, it should be the same width as the ribs- assuming the dog is not slab sided.

Tail docked at approximately the 2nd joint, appears to be a continuation of the spine and is carried only slightly above the horizontal when the dog is alert – tail length varies from one to three joints. One joint appears very short, while three can be quite long. The correct tail appears to be a continuation of the spine and is carried just above horizontal (when the dog is alert). The tail carriage is out, rather than up. Thus if you were looking at a clock, 3 o’clock is obviously horizontal, the correct tail placement is around 2 o’clock, much lower carriage than usually seen. A higher tail does not look like a continuation of the spine and generally indicates a flat, rather than slightly rounded croup. This may be pleasing to the eye, but it INCORRECT structure! If you had the same degree of `incorrectness’ in the front, it would be like saying you like a straight shoulder — that a straight shoulder is pleasing!

Tail carriage (slightly above the horizontal when the dog is alert) (3 o’clock is horizontal)

|

At 2 o’clock

|

At 1 o’clock

|

At 12 o’clock

|

|

|

|

|

Click the following links to read more articles in the “Dobermans in Detail” series:

Size, proportion &substance

Head

Neck Topline and Body

Forequarters

Hindquarters

Coat

Gait

Temperament

Conclusion: test yourself

by Linka Krukar submitted by Marj Brooks

Breeder/Exhibitor Ed, Breeding/Genetics

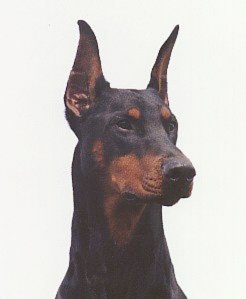

Long and dry, resembling a blunt wedge in both frontal and profile views. When seen from the front, the head widens gradually toward the base of the ears in a practically unbroken line. Eyes almond shaped, moderately deep set, with vigorous, energetic expression. Iris, of uniform color, ranging from medium to darkest brown in black dogs; in reds, blues, and fawns the color of the iris blends with that of the markings, the darkest shade being preferable in every case. Ears normally cropped and carried erect. The upper attachment of the ear when held erect, is on a level with the top of the skull. Top of skull flat, turning with slight stop to bridge of muzzle, with muzzle line extending parallel to top line of skull. Cheeks flat and muscular. Nose solid black on black dogs, dark brown on red ones, dark gray on blue ones, dark tan on fawns. Lips lying close to the jaws. Jaws full and powerful, well filled under the eyes.

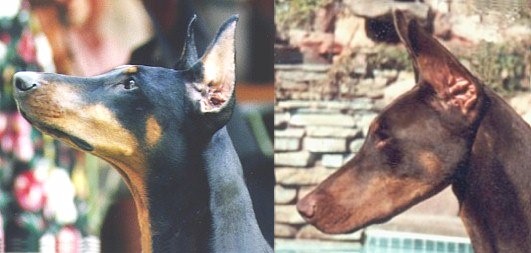

When judging the head, examination requires three views.

- Full front looking down on the head

- Full profile

- A ½ front view to assess the proportion of the head to the body.

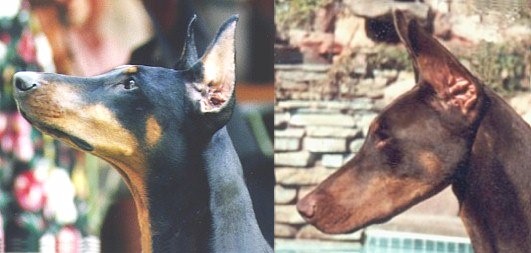

Long and dry, resembling a blunt wedge in both frontal and profile views. When seen from the front, the head widens gradually toward the base of the ears in practically an unbroken line – the muzzle and top of the head appear to be the same length (ratio of 1:1). Jaws full and powerful, well filled under the eyes, which means when you put your hands on the side of the muzzle, there should be a “face” filling your hands. If not, the dog doesn’t have enough “fill” under the eyes. Fill under the eye is important for a correct head because the jaws must be full and powerful to hold the 42 strongly developed and correctly placed teeth.

From the side you should have the same impression of the head as from the front. This means the dog should have some underjaw, not just a chin with a lip over it to give the impression of a blunt wedge. Good underjaw can be seen from the front and profile view. The side view will show the flat skull with the line of the skull parallel to the line of the muzzle. The stop is `slight’, thus the ideal amount is more than a Collie and less than a Great Dane.

The head should be correctly proportioned for the body. The Doberman is not a “head” breed, so the basic question is whether the head fits the individual dog. That’s why it’s important to observe the head from different views.

|

|

|

Good underjaw can be seen from the profile view

|

Eyes almond shaped and moderately deep set, with vigorous, energetic expression – Round eyes give the dog a softer expression as does a shallower set eye. Eyes are moderately deep set, which means “middle” – not too deep and not too shallow. Because of the original purpose of the breed, a dark eye is much more desired. Black dogs with yellow/gold eyes, red dogs with green or yellow eyes, blue dogs with gold or gray eyes and fawns with blue or gold eyes are not desired, darker eyes are preferred. The standard states medium to dark brown eyes on a black dog, so are black eyes a deviation of the standard? If you notice any prominence to the eyes (color, shape, depth), it is most likely a deviation.

Ears normally cropped and carried erect – The original 1923 standard stated that ears were “well placed and clipped to a point”. Today’s standard is telling us that ears are either “usually cropped” or “cropped in a normal fashion”. What is a normal ear crop and should we now base our opinion of the dog’s ears on what someone has unnaturally done to our dogs? Obviously where the ears are placed on the head is more important than the crop. A bad ear crop can pull an ear down so they wing out, literally pull an ear down so it won’t stand erect, or distort the shape of the head altogether. Most ears are cropped very long and it’s difficult for the dogs to keep them up. Do NOT expect a dog to carry ears erect while gaiting, unless they are alert to something as they are moving. An exceptionally short crop can give the appearance of a shorter neck, shorter and wider muzzle. Since the standard states that ears are “normally” cropped, is an uncropped ear is a deviation of the standard? Rather than harshly penalize a dog with uncropped ears, determine if the ears are in proportion to the head and the placement is correct.

|

A short ear crop

|

A long ear crop

(what is usually seen)

|

Uncropped

|

|

|

|

|

Judge the dog on the ear placement and carriage, not the (man made) crop or lack there of. The dog on the left and middle are the same dog. The natural eared dog has a cowlick. A short ear crop or natural (uncropped) ear can give the illusion of a wider head, shorter muzzle and shorter neck.

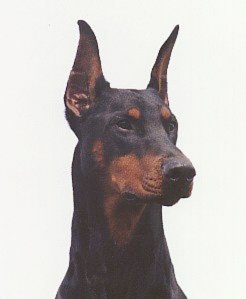

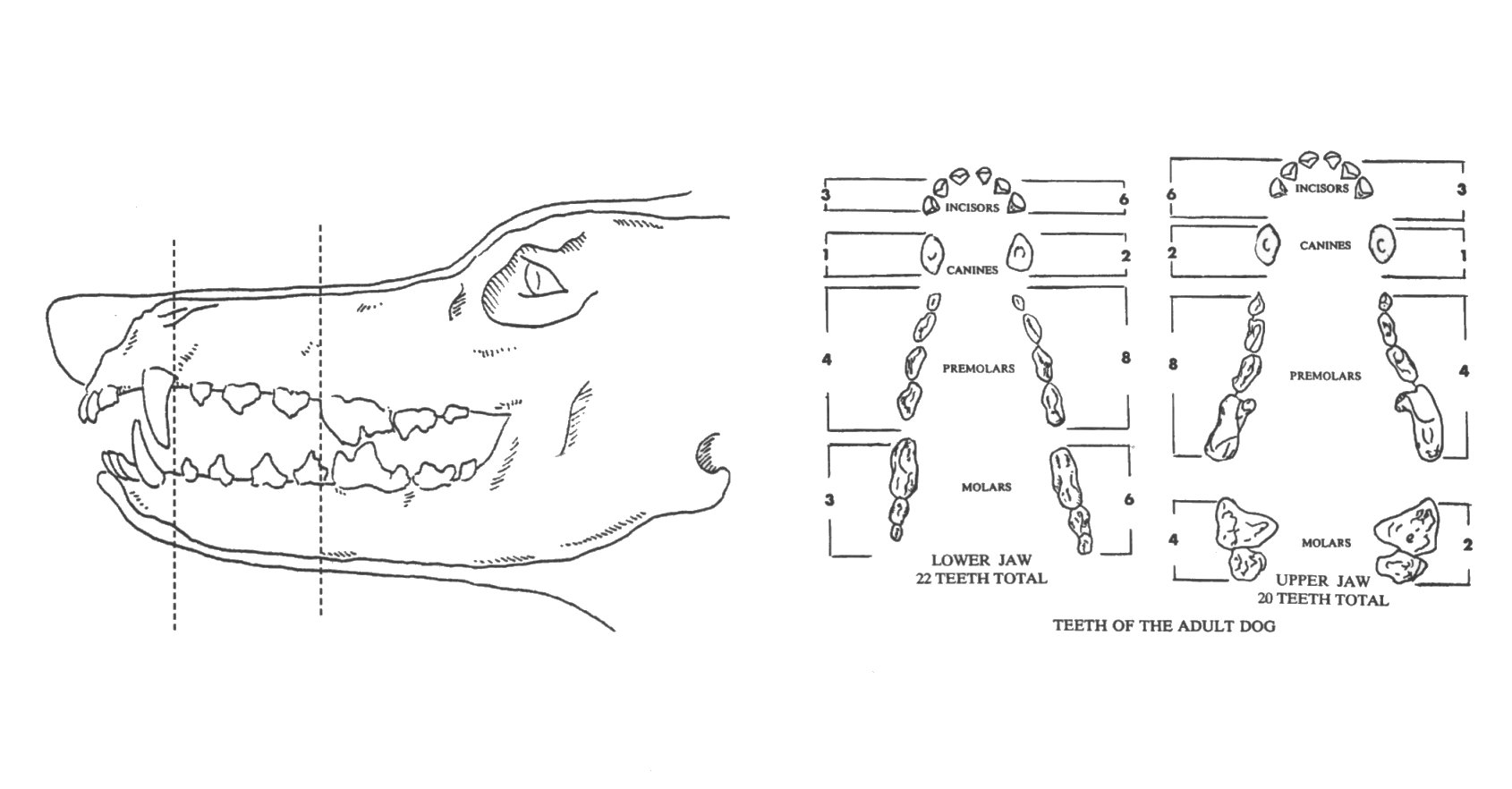

Teeth strongly developed and white. Lower incisors upright and touching inside of upper incisors- a true scissors bite. 42 correctly placed teeth, 22 in the lower, 20 in the upper jaw. Distemper teeth shall not be penalized. Disqualifying Faults: Overshot more than 3/16 of an inch. Undershot more than 1/8 of an inch. Four or more missing teeth.

Teeth strongly developed and white. Lower incisors upright and touching inside of upper incisors – a true scissors bite. 42 correctly placed teeth, 22 in the lower, 20 in the upper jaw. Distemper teeth shall not be penalized. Disqualifying Faults: Overshot more than 3/16 of an inch. Undershot more than 1/8 of an inch. Four or more missing teeth.

There is a purpose for such emphasis on this strong head – to hold the strongly developed (good size

d) teeth. Since three of the four disqualifications are in the mouth, it is important know what a correct mouth looks like and be accurate when counting teeth. The standard assumes that you know the names of all the teeth. Correctly placed teeth lets you know that a missing tooth replaced by an extra tooth is a deviation from the standard and must be considered as a fault. You may have 42 correctly placed teeth, and extra teeth in the spaces – consider this as a deviation from the required “correctly placed” teeth. It is not the same as missing teeth, which lead to a disqualification, but a deviation and should be considered to the extent that they affect occlusion and the number of extra teeth. To say that a dog with 3 extra teeth is the same as having a dog with 3 missing teeth is incorrect. The standard is clear that 4 missing teeth is a disqualification, it does NOT state that 4 extra teeth is a disqualification; but a deviation.

The three disqualifications in the mouth — the requirement of a true scissors bite– overshot more than 3/16″ and undershot more than 1/8″ make up two disqualifications. The standard is clearly stating what a scissors bite is. No, we have no tool to measure the exact distance that makes up the over or undershot bite, but the standard is clear as to how far over or undershot we should tolerate – how close the `scissors’ should be. Without these `measures’ a “true scissors” bite is left to interpretation. Four or more missing teeth is the third disqualification in the mouth, so it is important to know how to count teeth and identify them.

|

The only way to check for missing teeth is to OPEN THE MOUTH.

|

|

A quick lesson in counting teeth:

The standard specifies the number of teeth, the correct placing of the teeth and by implication, occlusion, so be sure to check for all of these. The easiest way is to count teeth is in groups. On the top there are two groups of 3 and 3 (two groups of three teeth on each side) and in the lower jaw two groups of 4 and 3. The only way to check for missing teeth is to OPEN THE MOUTH. There is no way to determine if the back molars are present with the mouth closed. Overshot and undershot are deviations from the scissors bite. They are to be considered a fault the same as missing teeth. While a level bite is not correct, it is only a deviation from what is correct, and should be considered just as any other deviation, over faults that may be more important to the overall dog. Occlusion should be checked from the side as well as the front of the mouth. The only way to check for missing teeth is to OPEN THE MOUTH.

Click the following links to read more articles in the “Dobermans in Detail” series:

Size, proportion &substance

Head

Neck Topline and Body

Forequarters

Hindquarters

Coat

Gait

Temperament

Conclusion: test yourself

by Linka Krukar submitted by Marj Brooks

Breeder/Exhibitor Ed, Breeding/Genetics

Height at withers: Dogs 26 to 28 inches, ideal about 27 ½ inches; Bitches 24 to 26 inches, ideal about 25 ½ inches. The height, measured vertically from the ground to the highest point of the withers, equaling the length measured horizontally from the forechest to the rear projection on the upper thigh. Length of head, neck and legs in proportion to length and depth of body.

The Doberman is medium sized, with total balance of height to length. Correct size is one of the most important factors in maintaining breed type. Medium size refers to the combination of height and bulk. Height at the withers: Dogs 26-28″, Bitches 24-26″– It would be rare to see an adult dog or bitch in the conformation ring that is too small for the standard. The ideal 27 ½” male or 25 ½” bitch is usually one of the smaller dogs in the ring today. Today many bitches are over 26″ and dogs well over 28″. This is NOT correct!!! As an aside, on two occasions the DPCA membership voted to disqualify dogs one inch over the standard. While this has never been added to the standard, it does stress the importance that is placed on the correct height to remain a medium sized breed. Years ago a letter was sent to judges stressing the importance of the correct height.

When measuring the Doberman, measure height from the highest point of the wither (not the shoulder blade) to the ground . Measure length from the forechest to the rear projection of the upper thigh. Know where those parts are and know what correct size looks like. A longer neck may give the dog the appearance of being taller than he is. The length of head, the neck and the legs are in proportion to length and depth of body- all the parts fit together. No one part stands out, they all flow together to make one picture.

If any part stands out, whether exceptionally good or bad, it will be distracting from the total picture. The height and length are equal, and the depth of body is equal to the length of leg. Just as the height/length was measured as equal, now the measurement of the wither to the elbow and then elbow to the ground should be the same. When these proportions are equal, a square dog generally appears too long, and/or too short on leg. Based on the description, a dog in perfect balance will also have a head the same length as the length of the neck.

Click the following links to read more articles in the “Dobermans in Detail” series:

Size, proportion &substance

Head

Neck Topline and Body

Forequarters

Hindquarters

Coat

Gait

Temperament

Conclusion: test yourself

by Linka Krukar submitted by Marj Brooks

Breeder/Exhibitor Ed, Breeding/Genetics

The Doberman Pinscher standard is probably one of the most precise and clearly written standards around today. It leaves very little out, and clearly states that any deviation from it’s description is penalized to the extent of that deviation. If it is NOT stated in the standard, it IS a deviation- that’s very clear! To understand Doberman structure, it’s important to know it’s original purpose. The Doberman was originally bred for its character, but designed to be geometrically and esthetically perfect. It began with what they wanted the dog to do– watchdog, guard dog, fearless, a short backed galloper, agile, fast, powerful and sturdy; to mention just a few things. Features for beauty were “built in” to the mathematical outline.

The standard, from beginning to end, demands an orderly and harmonious arrangement of parts to create a statically and kinetically balanced dog. Thus whether the dog is standing or moving, the parts must be in total harmony. The impression of the dog should be the same, whether the dog is in motion or stationary. The key to the Doberman is balance and proportion. All the parts fit into the other parts smoothly with no distractions. If any part stands out, whether good or bad, it takes away from the total picture and the balance and proportion is disrupted. As you go through the standard, you will see just how specific the description of the Doberman Pinscher is. Some points are so important, they are referred to in more than one section of the standard. To ignore the standard is an injustice to the breed and will change the Doberman forever.

GENERAL CONFORMATION AND APPEARANCE

The appearance is that of a dog that is of medium size, with a body that is square. Compactly built, muscular and powerful, for great endurance and speed. Elegant in appearance, of proud carriage, reflecting great nobility and temperament. Energetic, watchful, determined, alert, fearless, loyal and obedient.

This is the single most important paragraph in the standard.

In evaluating the Doberman, the first directive under general conformation and appearance is a dog of medium size (which is specified in more detail later in the standard). The reference to size includes a combination of height, bone, and substance (or bulk). The ideal bone and substance needed for correct balance is always in relation to a dog’s height. The taller dog requires more bone and substance for correct balance than a dog at the lower height limit of the standard. Since there is a diversity in the top and bottom limits of height, the dog must be considered as an individual and not compared to others when evaluating this. Height can be deceiving depending upon the amount of bone and/or substance a dog has. Size is a fundamental breed characteristic so it is very important that the Doberman has the appearance of a medium sized dog. The standard requires a combination of endurance and speed that could only be achieved in a medium sized dog. Size is very important! A medium sized Doberman is more agile and has good endurance, but still has enough size to generate the power needed to function successfully as a working dog. A dog larger than the specified proportions is approaching a giant breed, not a Doberman!

In the very beginning and throughout the standard, balance (or proportion) is probably stressed more than any other single point. By stating that the body is square, we have the first reference to balance- a dog of balanced proportions, balance being essential to soundness. Square means that the dog’s body is in horizontal and vertical balance, which also means the angles at both ends must match. Keep in mind that the standard states that it is the BODY that appears square, not the entire outline of the dog! In fact, a dog that looks square is probably too short!! Angles affect the appearance of square, with the straight, upright dog appearing more square than the dog of the same proportions with more angulation, who will appear longer in length.

Compactly built indicates that the dog should have a short, solid physique. Muscular and powerful indicates that the dog is in good condition with hard muscle, thus capable of performing effectively. The Doberman is an athlete. To have speed also, the dog must be in correction proportion of bone to substance and not so heavily boned or muscular so as to become too cumbersome. Thus the other extreme of fine boned or spindly is equally unacceptable.

Elegant in appearance, of proud carriage, reflecting great nobility and temperament-

Elegant does not mean fine boned, weak or delicate. The dog should look “poured” into it’s skeleton, all one piece. The naturally arched neck flows into smooth shoulders which continue to the strong, level topline, with no lumps, bumps or dips; continuing on to the tail, which appears to be a continuation of the spine. The coat is short, hard, shiny, and fits so smoothly over the body that the dog looks poured into it. Elegance is tasteful beauty of manner, form or style. Some other words for elegant are aristocratic, balanced, beautiful, dignified, graceful, harmonious, sleek, stately, stylish. To achieve this look, the dog must also be able to stand regally on its own without the benefit of being molded by its handler.

Proud carriagereflects how the dog feels about himself, indicating a high opinion of himself, a feeling of confidence, a spirited manner; all which relate to temperament. A dog that exudes confidence will naturally have a proud carriage and should have a sound, steady temperament.

Energetic means possessing, exerting or displaying vitality and intensity of expression; lively, powerful, and spirited. This breed characteristic is often displayed by a dog that appears to be filled with controlled energy. A dog that hangs its head, is listless or plods along behind the handler is not displaying much `energy’.

Watchful means vigilant, closely observant, being alert and aware of the surroundings and reacting to them. The dog shouldn’t be wary or cautious unless the situation calls for these reactions. A dog that remains aware of the judge’s approach by moving his head to glance at the judge or flicking the ears after the examination is being watchful. The dog that only responds to bait is not demonstrating this characteristic. Some dogs take a little longer to focus on bait when asked to freebait after gaiting because they may be more aware of what’s going on around them than the immediate interest in bait.

Determinedincludes firmness of purpose, resolve, and fixed intention. An example of this could be the dog that takes notice of something on the ground while gaiting and the next time around takes the opportunity to get a closer look (or taste). The dog may refuse to face a certain direction

or refuse to walk in a certain area. It is a strong- minded breed.

Alert refers to being vigilantly attentive, aware, mentally responsive and perceptive, quick. To be alert, the dog should be ready to react to anything they consider unusual. It doesn’t mean staring at bait, ignoring what goes on around him. In this case, staring at bait may be trained!

Fearless, the absence of fear, also includes brave, courageous (which implies consciously rising to a specific test by drawing on a reserve of inner strength), intrepid (invulnerability to fear), and bold (which stresses not only the readiness to meet danger or difficulty, but often also a tendency to seek it out). The fearless dog’s reaction to something new or unusual is to stand ready. The judge should be able to approach the dog when standing on a loose leash.

Loyal refers to being faithful to a person or duty. This trait may not be possible to evaluate in the show ring, but is demonstrated to the person who cares for the dog.

Obedience is demonstrated in the dog’s behavior and response to the person handling the dog, the judge, and his surroundings. While some of these qualities are not immediately evident in the conformation ring, they are observed in varying degrees depending on the situation. Dobermans should not be robots, paying attention to only the bait, standing perfectly like a statue. They should respond to everything going on around them which does include the bait, other dogs, people, sounds, etc.

Assessing temperament begins with `reading’ the dog’s eyes. Look for an interested, confident, curious dog, that is ready for anything and sure that he can handle anything that comes his way. The characteristics of behavior are very important to the total picture of the Doberman, just as the physical attributes that follow are.

As previously stated, the statements in this section make up the single most important paragraph in the standard- if you remember what it is telling you about the breed, the other parts of the standard fall into place.

|

|

|

|

Outline of dog

|

Outline of bitch

|

Click the following links to read more articles in the “Dobermans in Detail” series:

Size, proportion &substance

Head

Neck Topline and Body

Forequarters

Hindquarters

Coat

Gait

Temperament

Conclusion: test yourself

by Linka Krukar submitted by Marj Brooks

Breeder/Exhibitor Ed, Breeding/Genetics

|

Surprising as it may seem, it isn’t capacity that explains the differences that exist between individuals because most seem to have far more capacity than they will ever use. The differences that exist between individuals seem to be related to something else. The ones who achieve and out perform others seem to have within themselves the ability to use hidden resources. In other words, it’s what they are able to do with what they have that makes the difference.

In many animal-breeding programs the entire process of selection and management is founded on the belief that performance is inherited. Attempts to analyze the genetics of performance in a systematic way have involved some distinguished names such as Charles Darwin and Francis Galton. But it has only been in recent decades that good estimates of heritability of performance have been based on adequate data. Cunningham (1991) in his study of horses found that only by using Timeform data, and measuring groups of half brothers and half sisters could good estimates of performance be determined. His data shows that performance for speed is about 35% heritable. In other words only about 35% of all the variation that is observed in track performance is controlled by heritable factors, the remaining 65% are attributable to other influences, such as training, management and nutrition. Cunningham’s work while limited to horses provides a good basis for understanding how much breeders can attribute to the genetics and the pedigrees.

Researchers have studied this phenomena and have looked for new ways to stimulate individuals in order to improve their natural abilities. Some of the methods discovered have produced life long lasting effects. Today, many of the differences between individuals can now be explained by the use of early stimulation methods.

|

|

|

Introduction

|

|

Man for centuries has tried various methods to improve performance. Some of the methods have stood the test of time, others have not. Those who first conducted research on this topic believed that the period of early age was a most important time for stimulation because of its rapid growth and development. Today, we know that early life is a time when the physical immaturity of an organism is susceptible and responsive to a restricted but important class of stimuli. Because of its importance many studies have focused their efforts on the first few months of life.

Newborn pups are uniquely different than adults in several respects. When born their eyes are closed and their digestive system has a limited capacity requiring periodic stimulation by their dam who routinely licks them in order to promote digestion. At this age they are only able to smell, suck, and crawl. Body temperature is maintained by snuggling close to their mother or by crawling into piles with other littermates. During these first few weeks of immobility researchers noted that these immature and under-developed canines are sensitive to a restricted class of stimuli which includes thermal, and tactile stimulation, motion and locomotion.

Other mammals such as mice and rats are also born with limitations and they also have been found to demonstrate a similar sensitivity to the effects of early stimulation. Studies show that removing them from their nest for three minutes each day during the first five to ten days of life causes body temperatures to fall below normal. This mild form of stress is sufficient to stimulate hormonal, adrenal and pituitary systems. When tested later as adults, these same animals were better able to withstand stress than littermates who were not exposed to the same early stress exercises. As adults, they responded to stress in “a graded” fashion, while their non-stressed littermates responded in an “all or nothing way.”

Data involving laboratory mice and rats also shows that stress in small amounts can produce adults who respond maximally. On the other hand, the results gathered from non-stressed littermate show that they become easily exhausted and would near death if exposed to intense prolonged stress. When tied down so they were unable to move for twenty-four hours, rats developed severe stomach ulcers, but litter mates exposed to early stress handling were found to be more resistant to stress tests and did not show evidence of ulcers. A secondary affect was also noticed.

Sexual maturity was attained sooner in the littermates given early stress exercises. When tested for differences in health and disease, the stressed animals were found to be more resistant to certain forms of cancer and infectious diseases and could withstand terminal starvation and exposure to cold for longer periods than their non-stressed littermates. Other studies involving early stimulation exercises have been successfully performed on both cats and dogs. In these studies, the Electrical Encephalogram (EEG) was found to be ideal for measuring the electrical activity in the brain because of its extreme sensitivity to changes in excitement, emotional stress, muscle tension, changes in oxygen and breathing. EEG measures show that pups and kittens when given early stimulation exercises mature at faster rates and perform better in certain problem solving tests than non-stimulated mates. In the higher level animals the effect of early stimulation exercises have also been studied. The use of surrogate mothers and familiar objects were tested by both of the Kelloggs’ and Dr. Yearkes using young chimpanzees. Their pioneer research shows that the more primates were deprived of stimulation and interaction during early development, the less able they were to cope, adjust and later adapt to situations as adults.

While experiments have not yet produced specific information about the optimal amounts of stress needed to make young animals psychologically or physiologically superior, researches agree that stress has value. What also is known is that a certain amount of stress for one may be too intense for another, and that too much stress can retard development. The results show that early stimulation exercises can have positive results but must be used with caution. In other words, too much stress can cause pathological adversities rather than physical or psychological superiority. |

|

Methods of Stimulation

|

|

The U.S. Military in their canine program developed a method that still serves as a guide to what works. In an effort to improve the performance of dogs used for military purposes, a program called “Bio Sensor” was developed. Later, it became known to the public as the “Super Dog” Program. Based on years of research, the military learned that early neurological stimulation exercises could have important and lasting effects. Their studies confirmed that there are specific time periods early in life when neurological stimulation has optimum results. The first period involves a window of time that begins at the third day of life and lasts until the sixteenth day. It is believed that because this i

nterval of time is a period of rapid neurological growth and development, and therefore is of great importance to the individual.

The “Bio Sensor” program was also concerned with early neurological stimulation in order to give the dog a superior advantage. Its development utilized six exercises which were designed to stimulate the neurological system. Each workout involved handling puppies once each day. The workouts required handling them one at a time while performing a series of five exercises. Listed in order of preference the handler starts with one pup and stimulates it using each of the five exercises. The handler completes the series from beginning to end before starting with the next pup. The handling of each pup once per day involves the following exercises:

- Tactical stimulation (between toes)

- Head held erect

- Head pointed down

- Supine position

- Thermal stimulation

|

1. Tactile stimulation

Holding the pup in one hand, the handler gently stimulates (tickles) the pup between the toes on any one foot using a Q-tip. It is not necessary to see that the pup is feeling the tickle. Time of stimulation 3 – 5 seconds.

(Figure 1)

|

Figure 1 |

-

- Figure 2

|

2. Head held erect

Using both hands, the pup is held perpendicular to the ground, (straight up), so that its head is directly above its tail. This is an upwards position. Time of stimulation 3 – 5 seconds (Figure 2).

|

|

3. Head pointed down

Holding the pup firmly with both hands the head is reversed and is pointed downward so that it is pointing towards the ground. Time of stimulation 3 – 5 seconds (Figure 3).

|

Figure 3 |

Figure 4 |

4. Supine position

Hold the pup so that its back is resting in the palm of both hands with its muzzle facing the ceiling. The pup while on its back is allowed to sleep struggle. Time of stimulation 3-5 seconds. (Figure 4)

|

|

5. Thermal stimulation

Use a damp towel that has been cooled in a refrigerator for at least five minutes. Place the pup on the towel, feet down. Do not restrain it from moving. Time of stimulation 3-5 seconds. (Figure 5)

|

-

- Figure 5

|

|

|

These five exercises will produce neurological stimulations, none of which naturally occur during this early period of life. Experience shows that sometimes pups will resist these exercises, others will appear unconcerned. In either case a caution is offered to those who plan to use them. Do not repeat them more than once per day and do not extend the time beyond that recommended for each exercise. Over stimulation of the neurological system can have adverse and detrimental results. These exercises impact the neurological system by kicking it into action earlier than would be normally expected. The result being an increased capacity that later will help to make the difference in its performance. Those who play with their pups and routinely handle them should continue to do so because the neurological exercises are not substitutions for routine handling, play socialization or bonding. |

| Benefits of Stimulation |

|

Five benefits have been observed in canines that were exposed to the Bio Sensor stimulation exercises. The benefits noted were:

Improved cardio vascular performance (heart rate) Stronger heart beats Stronger adrenal glands More tolerance to stress and Greater resistance to disease.

In tests of learning, stimulated pups were found to be more active and were more exploratory than their non- stimulated littermates over which they were dominant in competitive situations.

Secondary effects were also noted regarding test performance. In simple problem solving tests using detours in a maze, the non-stimulated pups became extremely aroused, whined a great deal, and made many errors. Their stimulated littermates were less disturbed or upset by test conditions and when comparisons were made, the stimulated littermates were more calm in the test environment, made fewer errors and gave only an occasional distress when stressed.

|

| Socialization |

|

As each animal grows and develops three kinds of stimulation have been identified that impact and influence how it will develop and be shaped as an individual. The first stage is called early neurological stimulation, and the second stage is called socialization. The first two (early neurological stimulation and socialization) have in common a window of limited time. When Lorenz, (1935) first wrote about the importance of the stimulation process he wrote about imprinting during early life and its influence on the later development of the individual. He states that it was different from conditioning in that it occurred early in

life and took place very rapidly producing results which seemed to be permanent. One of the first and perhaps the most noted research efforts involving the larger animals was achieved by Kellogg & Kellogg (1933). As a student of Dr. Kellogg’s I found him and his wife to have an uncanny interest in children and young animals and the changes and the differences that occurred during early development. Their history making study involved raising their own new born child with a new born primate. Both infants were raised together as if they were twins. This study like others that would follow attempted to demonstrate that among the mammals there are great differences in their speed of physical and mental development. Some are born relatively mature and quickly capable of motion and locomotion, while others are very immature, immobile and slow to develop. For example, the Rhesus monkey shows rapid and precocious development at birth, while the chimpanzee and the other “great apes” take much longer. Last and slowest is the human infant.

One of the earliest efforts to investigate and look for the existence of socialization in canines was undertaken by Scott-Fuller (1965). In their early studies they were able to demonstrate that the basic technique for testing the existence of socialization was to show how readily adult animals would foster young animals, or accept one from another species. They observed that with the higher level animals it is easiest done by hand rearing. When the foster animal transfers its social relationships to the new species, researchers conclude that socialization has taken place. Most researchers agree that among all species, a lack of adequate socialization generally results in unacceptable behavior and often times produces undesirable aggression, excessiveness, fearfulness, sexual inadequacy, and indifference toward partners.

Socialization studies confirm that the critical periods for humans (infant) to be stimulated are generally between three weeks and twelve months of age. For canines the period is shorter, between the fourth and sixteenth week of age. During these critical time periods two things can go wrong. First, insufficient social contact can interfere with proper emotional development which can adversely affected the development of the human bond. The lack of adequate social stimulation, such as handling, mothering and contact with others, adversely affects social and psychological development.

Second, over mothering can prevent sufficient exposure to other individuals, and situations that have an important influence on growth and development. The literature shows that humans and animals respond in similar ways when denied minimal amounts of stimulation. In humans, the absence of love and cuddling increases the risk of an aloof, distant, asocial or sociopathic individual. Over mothering can also have its detrimental effects. It occurs when a patient insulates the child from outside contacts, or keeps the apron strings tight, thus limiting opportunities to explore and interact. In the end, over mothering generally produces a dependent, socially maladjusted and sometimes emotionally disturbed individual.

The absence of outside social interactions for both children and pups usually results in a lack of adequate learning and social adjustment. Protected youngsters who grow up in an insulated environment often times become sickly, despondent, lacking in flexibility and unable to make simple social adjustments. Generally, they are unable to function productively or to interact successfully then they become adults.

Owners who have busy life styles with long and tiring work and social schedules often times cause pets to be neglected. Left to themselves with only an occasional trip out of the house or off of the property they seldom see other canines or strangers and generally suffer from poor stimulation and socialization. For many, the side effects of loneliness and boredom set-in. The resulting behavior manifests itself in the form of chewing, digging, and hard to control behavior (Battaglia).

It seems clear that small amounts of stress followed by early socialization can produce beneficial results. The danger seems to be in not knowing where the thresholds are for over and under stimulation. Many improperly socialized youngsters develop into older individuals unprepared for adult life, unable to cope with its challenges, and interactions. Attempts to re-socialize them when adults have only produced small gains. These failures confirm the notion that the window of time open for early neurological and social stimulation only comes once. After it passes, little or nothing can be done to overcome the negative effects of too much or too little stimulation.

The third and final stage in the process of growth and development is called enrichment. Unlike the first two stages it has no time limit and by comparison covers a very long period of time. Enrichment is a term which has come to mean the positive sum of experiences, which have a cumulative effect upon the individual. Enrichment experiences typically involve exposure to a wide variety of interesting, novel, and exciting experiences with regular opportunities to freely investigate, manipulate, and interact with them. When measured in later life, the results show that those reared in an enriched environment tend to be more inquisitive and are more able to perform difficult tasks. The educational TV program called Sesame Street is perhaps the best known example of a children’s enrichment program. The results show that when tested, children who regularly watched this program performed better than playmates who did not. Follow up studies show that those who regularly watched Sesame tend to seek a college education and when enrolled, performed better than playmates who were not regular watchers of the Sesame Street Program.

There are numerous children studies that show the benefits of enrichment techniques and programs. Most focus on improving self-esteem and self-talk. Follow up studies show that the enriched Sesame Street students when later tested were brighter and scored above average and most often were found to be the products of environments that contributed to their superior test scores. On the other hand, those whose test scores were generally below average, (labeled as dull) and the products of underprivileged or non- enriched environments often times had little or only small amounts of stimulation during early childhood and only minimal amounts of enrichment during their developmental and formative years. Many were characterized as children who grew up with little interaction with others, poor parenting, few toys, no books and a steady diet of TV soap operas.

A similar analogy can be found among canines. All the time they are growing they are learning because their nervous systems are developing and storing information that may be of inestimable use at a later date. Studies by Scott and Fuller confirm that non-enriched pups when given free choice preferred to stay in their kennels. Other litter mates who were given only small amounts of outside stimulation between five and eight weeks of age were found to be very inquisitive and very active. When kennel doors were left open, the enriched pups would come bounding out while littermates who were not exposed to enrichment would remain behind. The non-stimulated pups would typically be fearful of unfamiliar objects and generally preferred to withdraw rather than investigate. Even well bred pups of superior pedigrees would not explore or le

ave their kennels and many were found difficult to train as adults. These pups in many respects were similar to the deprived children. They acted as if they had become institutionalized, preferring the routine and safe environment of their kennel to the stimulating world outside their immediate place of residence.

Regular trips to the park, shopping centers and obedience and agility classes serve as good examples of enrichment activities. Chasing and retrieving a ball on the surface seems to be enriching because it provides exercise and includes rewards. While repeated attempts to retrieve a ball provide much physical activity, it should not be confused with enrichment exercises. Such playful activities should be used for exercise and play or as a reward after returning from a trip or training session. Road work and chasing balls are not substitutes for trips to the shopping mall, outings or obedience classes most of which provide many opportunities for interaction and investigation.

Finally it seems clear that stress early in life can produce beneficial results. The danger seems to be in not knowing where the thresholds are for over and under stimulation. However, the absence or the lack of adequate amounts of stimulation generally will produce negative and undesirable results. Based on the above it is fair to say that the performance of most individuals can be improved including the techniques described above. Each contributes in a cumulative way and supports the next stage of development. |

|

Conclusion

|

|

Breeders can now take advantage of the information available to improve and enhance performance. Generally, genetics account of about 35% of the performance but the remaining 65% (management, training, nutrition) can make the difference. In the management category it has been shown that breeders should be guided by the rule that it is generally considered prudent to guard against under and over stimulation. Short of ignoring pups during their first two months of life, a conservative approach would be to expose them to children, people, toys and other animals on a regular basis. Handling and touching all parts of their anatomy is also necessary to learn as early as the third day of life. Pups that are handled early and on a regular basis, generally do not become hand shy as adults.

Because of the risks involved in under stimulation a conservative approach to using the benefits of the three stages has been suggested based primarily on the works of Arskeusky, Kellogg, Yearkes and the “Bio Sensor” program (later known as the “Super Dog Program”).

Both experience and research have dominated the beneficial effects that can be achieved via early neurological stimulation, socialization and enrichment experiences. Each has been used to improve performance and to explain the differences that occur between individuals, their trainability, health and potential. The cumulative effects of the three stages have been well documented. They best serve the interests of owners who seek high levels of performance when properly used. Each has a cumulative effect and contributes to the development and the potential for individual performance. |

|

REFERENCES:

|

|

-

Battaglia, C.L., “Loneliness and Boredom” Doberman Quarterly, 1982.

-

Kellogg, W.N. & Kellogg, The Ape and the Child, New York: McGraw Hill. Scott & Fuller, (1965)

-

Dog Behavior -The Genetic Basics, University Chicago Press Scott, J.P., Ross, S., A.E. and King D.K. (1959)

-

The Effects of Early Enforced Weaning on Stickling Behavior of Puppies, J. Genetics Psychologist, p5: 261-81.

|

|

- originally published as “Early Neurological Stimulation”

- reprinted with permission by Dr. Carmen L. Battaglia

- photos and articles submitted by Marj Brooks, USA

|

Breeder/Exhibitor Ed, Breeding/Genetics

- Reprinted with permission

- Written and submitted by Ms Dany Canino

SOME ANSWERS TO THAT IMPORTANT QUESTION

WHAT IS NEUTERING? This is a surgical procedure to sterilize a male dog, oftentimes called castration. Both testicles are removed so that the dog is incapable of reproducing.

WHEN SHOULD IT BE DONE? Usually after both testicles have completely descended into the scrotum or anytime after 5 months of age.

WHAT ABOUT DOING A VASECTOMY INSTEAD? This procedure does render a male sterile, but because the male hormone (testosterone) is carried through the testicles, a vasectomy will not eliminate the male from having sexual desires or sexual tendencies such as; marking territory, roaming instinct, and sexual aggression against other male dogs.

SHOULD I USE MY MALE AT STUD JUST ONCE BEFORE I NEUTER HIM? This one is

multi-faceted in answer. Making the decision to allow your male to sire a litter of puppies is a lifetime responsibility. Your position as the stud owner should not end after your male has serviced the female. Those puppies that will be born as a result of your male´s sperm have to be placed into good lifetime homes. Another factor to consider is that every breed of dog is affected with different genetic problems. You would have to be a professional breeder to know what these defects were and, therefore, could be very selective as to which female the male is bred to. Otherwise you might very well be passing these same defects onto some innocent puppies and unsuspecting puppy buyers.

If you purchased your male from a pet store it probably originally came from a puppy mill, NOT A PROFESSIONAL BREEDER. This means that it´s almost impossible to check out his genetic background as so many of these people breed mother to son, sister to brother, etc, etc. These people do not “fess up” to this breeding practice and they are not above falsifying the pedigrees. That´s why the American Kennel Club has had to close down so many of these places. If your pup came from a pet shop you´ll have no concrete way of knowing what genetic faults you will be passing on if you breed your male.

WILL MY MALE BE LESS MASCULINE IF I NEUTER HIM? Your male doesn´t derive his courage from his testicles. It´s a known fact that many guard dogs and Police Dogs are neutered. This way there is more assurance that the dog will pay attention to business instead of some cute female that might wander near him. It´s quite understandable that the thought of neutering a male dog mostly affects men. They can´t help but empathize with the procedure. Male dogs that are neutered DO NOT become effeminate. These dogs will still be capable of protecting you and your property. Neutering simply means that the dog will loose his sexual desire and cannot reproduce.

HOW SOON AFTER NEUTERING CAN I EXERCISE MY DOG? You can usually take your dog for a walk the day after neutering him. If your dog is in obedience training he can resume this work a couple of days after neutering. By the end of the week everything will be back to normal.

WILL MY DOG LOOK REALLY DIFFERENT & WILL HE GET FAT? Right after your dog is neutered he won´t really look any different. He will almost look as if he still has his testicles. In time the scrotum skin will tighten up, but by then you won´t even be aware of it. As far as your dog getting fat, if you feed him properly (not too high in protein or fat) and give him exercise, there is no reason for him to get fat. A lack of hormones in your dog´s body doesn´t cause obesity in a dog. Owners are responsible for dogs getting fat.

WILL MY MALE RESENT BEING NEUTERED? Once he is neutered, especially if he is done young, he won´t even miss not having testicles. As far as resenting not being bred, if he´s never bred he won´t have any feelings about this at all. It has never been proven that male dogs experience the same sexual gratification as a human male through the sexual act.

WILL MY MALE LIVE LONGER IF I NEUTER HIM? You will certainly increase his chances of a longer life when it comes to the different forms of male cancer.

WHAT ARE SOME VALID REASONS FOR NEUTERING? One of the main reasons is the health of the animal. By neutering a male before he reaches adulthood or before his male hormones become active, you´re reducing the animal´s chances of testicular cancer, anal gland cancer, or prostate cancer. Many male animals that are left un-altered become “sexually aggressive”, not only towards other male dogs, but sometimes they even become “testy” towards people.

Every year millions of puppies and older dogs are put to sleep in animal shelters. So many of these animals are the product of people that wanted their male dog to experience the sexual act “just once”, or, they wanted to try and get a dog just like their male, or they thought their dog was so good looking that he should be shared.

NONE OF THESE REASONS ARE VALID ENOUGH TO BREED YOUR MALE.

All things considered, you´re probably better off leaving the breeding of animals to the experienced professionals.

I hope this question and answer sheet will help you to make a conscious decision. Feel free to discuss this important decision with your Veterinarian, because next to you, he´s your dog´s best friend. If you are still undecided have your male evaluated by a professional breeder of your breed to see if he or his pedigree are worthy of being reproduced.

Breeder/Exhibitor Ed, Breeding/Genetics

submitted with permission by Marj Brooks

with thanks to Kevin & Donna Frizzell of DeSaix St. Bernards for generously allowing us to use many of their superb array of articles

A comprehensive whelping kit should be collected and be ready for use at least two weeks prior to the expected delivery date. There is nothing worse that not being properly prepared and it can put the life of your bitch and the puppies at risk. We have listed what we have found to be most useful and no expense has been spared for the sake of convenience, or the compromise of safety or hygiene.

WE HAVE FOUND WE NEEDED:

- a good size whelping box with pig rails and flap

- waterproof tarp or plastic sheeting to protect the carpet under the whelping box

- whelp chart to record time ~ weight ~ markings ~ placenta deliveries

- at least 2 dozen towelling nappies (towels are too big and cumbersome)

- a good set of electronic weighing scales

- a phone near the whelping box with a list of emergency numbers

- a good lighting source

- a camera with a flash

- a video camera

- some newspapers for the dam to shred

- large rubbish bags for the newspapers after the dam has finished

- heaps of kylies (very useful as they absorb fluids and leave the surface dry)

- soft toys for the puppies

- a warm box to put them in after they are born to keep them together and safe

- a heating pad or infra red lamp

- orphan formula such as Biolac

- tubes of Nutrigel

- human type baby bottles and teats

- containers with lots of compartments for easy access and storage of equipment

- a sterilizer for feeding equipment

- feeding tubes

- sandoz calcium syrup for the dam

- brandy for the babies if they are sluggish

- 50% glucose solution for the babies if they are sluggish

- lots of baby wipes in case mom doesn’t want to clean up after them

- betadine solution for dew claw and umbilical cord care cotton buds large and small

- surgical spirits for umbilical cord care

- worming suspension

- sterile water

- Vaseline to smear on bums as the anus can become blocked externally with dried faeces

- assortment of sharp scissors

- haemostats (small) for clamping cord

- zip ties (small) excellent for tying off cords

- an assortment of different capacity syringes 1ml ~ 2.5ml ~ 5ml ~ 10ml ~ 20ml ~ 50ml

- rolls of elastoplast to cover sharp ends of trimmed zip ties

- cotton wool balls

- gentle puppy shampoo to clear up * accidents *

- small plastic bowl for holding water for toilet duties

We have found the best method (if intervention is needed) of separating the puppy from the afterbirths is:

- it requires two people one to work on the puppy and the other to separate it from the membranes

- gently squeeze the placenta prior to severing the cord – it gives the puppy maximal blood volume

- clamp the cord twice at 1″ and 1 1/4″ away from the puppy with the haemostats to crush the vessels

- secure zip tie on first clamp tight nearest the puppy and cut the cord at the other clamp site

- trim the tail of the zip tie as short as possible

- swab the remaining cord with betadine or surgical spirits

- allow to dry

- cover the zip tie and cord with elastoplast

- trim the cord below the zip tie (nearside of the puppy) to remove it after about 6 hours and re-swab

-

- 1ml Brandy

- 1ml Sandoz or 50% glucose solution

- 8ml Sterile Water

Puppies should be placed on the mother to feed as soon as possible after the birth to get the Colostrum necessary for immunity. Puppies can manage for several hours if overly lethargic without this. Below is the recipe for a solution to give lethargic puppies as source of energy and cardiac stimulant and then continue to attempt to get them to nurse.

In a 10ml syringe draw up:

~ Make sure the solution is warm and shake well prior to administering.

~ Administer 1/2 – 1ml no more than once an hour

Breeder/Exhibitor Ed, Breeding/Genetics

Submitted by Helayne Silver and designed by Carl Jeser

(Please click on any of the photos in order to view a larger picture)

We decided to build a whelping box that could be disassembled for storage. This caused me to construct the box somewhat differently then I would have if the box were not going to have to be disassembled. I was concerned about the structural integrity of the box and kept this in mind throughout the design and construction of the box. I tend to overbuild so you may not find it necessary to use as many screws as I did.

We chose to use melamine for the bottom and sides of the box. This material can be purchased at Home Depot or Lowes in 4´ by 8´ sheets as well as other sizes. This material has a plastic type surface that will not absorb liquids and can easily be cleaned. The cost per 4´ by 8´ sheet is approximately $25. The biggest disadvantage to the use of this material is its weight. It is heavier then equivalent size plywood. Its core is pressed wood and must be sealed if there is any potential contact with moisture. I chose to seal all raw edges with a coat of oil based primer and then a coat of latex primer and then a coat of exterior latex. This sealed the edges from moisture and made them very smooth to the touch. The flat, plastic coated, surfaces should not be painted, only the edges. The edges must be sanded smooth because after being cut the plastic surface at the edge can be very sharp and can easily cut flesh. You should be careful handling raw, unsanded edges. Once sanded and painted the edges offer no danger to you or your dogs. The three coats of paint applied to the edges results in a very smooth surface. It is also possible to apply a banding strip to the edge. It is also sold at home depot and has a heat activated adhesive on it. You can use an iron or a heat gun to apply the edge. I just felt it was easier to use the paint and that the use of the paint resulted in a satisfactory and safe edge. I also considered cutting slits in 1 ¼” diameter PVC and placing the PVC over the upper exposed edges of the sides. I will probably put the PVC over the top edges of the sides the next time we use the whelping box.

The bottom of the box is made of one sheet of 4´ by 8´ melamine. The sides of the box were made of 2´ by 8´ sheets of melamine. I purchased the sheets at Home Depot and had them cut a 4´ by 8´ sheet in half. Melamine sheets are usually 49″ by 99″ so be sure you or the person cutting the board measures to find the center of the sheet and does not assume the sheet is 48″ wide or you may wind up with the sides being different heights. You can cut the melamine sheets with a circular saw, a jig saw, or a hand saw. You may get some chipping of the plastic surface but it should be minor and you should be able to smooth the edge by sanding and if you paint the edges the chips will not be noticeable.

The windows were made by cutting out openings in the side pieces before the box was constructed. All of the cut edges were sanded, primed and painted. We chose to use 18″ by 24″ sheets of plastic. Home Depot and Lowes both sell this size sheet of plastic as well as several other sizes. I cut the window openings 2″ smaller then the sheet of plastic so that the plastic would overlap the openings by 1″ on sides and top and bottom. I drilled holes in the plastic about every 6″ around the perimeter of the plastic and mounted it to the sides using #4 round head screws 5/8″ long. I drilled the holes about ½” in from the outer edge of the plastic. I used the cheapest plastic sheets and once mounted it seems strong and there is little or no flex. I had debated about buying lexan but decided to try the less expensive material and it seems to be fine.

I decided that it would be best to have the sides sit on top of the bottom. I used 1 5/8″ drywall screws to mount the two long sides to the rear wall. I was very careful to drill pilot holes that were as close to the center of the edge of the rear wall as I could. You can feel the screw raise the surface of the bottom sheet as you are screwing in the screw if you are too close to the surface of the plastic film. This just means you are not in the center of the edge. If you feel this rise stop immediately and hopefully you will not break the plastic surface of the melamine. I placed screws at about 6″ intervals. After screwing the long sides to the rear wall I screwed a 1″ x 3″ board along the lower edge of the side and screwed through this board and into the edge of the bottom sheet of melamine. I was very careful to not penetrate the upper or lower surface of the melamine bottom. Again, this was done by feeling the surfaces as I screwed the screws in. I started out using a powered screw gun but this drove the screw in faster then I was able to feel the rise in the surface and I penetrated the melamine surface so I wound up screwing in the screws by hand so that I was able to feel the rise in the melamine surface before the screw penetrated the surface. I then went inside the box and approximately 1″ above the bottom of the box I used 1 1/4″ drywall screws to screw the side to the exterior 1″ by 3″. This length screw did not penetrate the exterior trim board. By using this method to attach the sides I achieved sufficient strength in the box that enabled me to avoid any bracing on the top of the box.

At the front opening of the box I used 1″ by 2″ trim boards at the front sides of the box and then 1″ by 3″ trim boards on the front of the box to provide strength to the box and to provide a slot for the front board to slide up and down in. The combination of the drywall screws and the various trim boards the box seems to have sufficient strength without any additional bracing.

Because we wanted to be able to move the box around we mounted the box on dollies. We support the ends of the box and also the middle of the box. Without support in the middle of the bottom, the box will bend. I had the dollies available so it was easier for me to choose to use them rather then to figure out some other solution. If you had no need to move the box, it could certainly be set directly on the floor.

We divided the interior of the box into two areas. The rear of the box is 32 inches deep with a divider and the front of the box is 64″ long. The divider was made of ¼” plywood to make it light weight and easily removable for cleaning or whatever. The guides for the divider were made of 1″ by 2″ boards mounted vertically about ¼” apart. For the divider and the front boards we found it was easier to get the boards in and out if the runners were not tight against the divider. Even when the mother rolled against the divider

it did not pop out of the runners. The front boards are standard 1″ by lumber cut to the length equal to the front opening.

The “pig” rails are made of 2″ diameter PVC cut to fit the front of the box. PVC hangers are used to hang the PVC around the box. The PVC and the hangers are available in the plumbing department of Home Depot or Lowes. The hangers are screwed to the wall at the height best for your bitch; probably 6 to 9 inches above the bottom of the box.

The PVC can be snapped in and out of the hangers so it makes it convenient for cleaning and moving things around in the box. The rails are only in the front portion of the box and not in the rear compartment since the mother can not get into the rear compartment.

The dimensions of the box are as follows:

-

Bottom of box – 49″ by 97″

-

Two long sides of box – 24 ½” by 96″

-

Rear side – 24 ½” by 49″

-

Divider – 22″ by 47 ¼”

-

Window openings – 16″ by 22″

-

Boards for front opening – 47 ¼” long

(We used 1″ by 4″, 1″ by 6″, and 1″ by 12″ boards cut to 47 ¼” long and stacked them as needed to establish the desired height to prevent the mother from leaving the whelping box)

After reading what I have written, I must say this whelping box is easy to build. I think it was easier to build then to explain how to build it. Drilling the pilot holes into the edges and screwing in the screws is the most difficult part just because you have to be so careful when performing these two tasks.

Breeder/Exhibitor Ed, Breeding/Genetics

written & submitted by Judy Doniere, USA

You might be interested in how our whelping box is constructed. I’ve used the same type since the late 50’s and wouldn’t even try another. Partner Sue had hubby construct hers the same.

You might be interested in how our whelping box is constructed. I’ve used the same type since the late 50’s and wouldn’t even try another. Partner Sue had hubby construct hers the same.

Get 4X8 plywood (you can cut it down to 4 X 6 if you don’t have the space), 1/2 inch thick. Attach sturdy wheels like on a crate cart to each corner.

Add 2 ft. high side walls around. Have a center board 2 foot high as well divide the box. Cut a door in center that will swing open and hook open or a slide bold to shut. Keep a 3 inch high lip. Door is about 12 or 13 inches wide.

At the near end of box, cut out another door way but this one will be in 2 sections secured with piano hinges so you can drop down the first half to let bitch jump in but keep older pups from climbing out. It will also drop all the way down and will fold under box when pups are very young.

with piano hinges so you can drop down the first half to let bitch jump in but keep older pups from climbing out. It will also drop all the way down and will fold under box when pups are very young.

The idea for this is that you have one side for young pups the first 3 weeks, but mom can go to other side to get away from them without leaving box.

The best thing is that when they are 3 wks. old, they will climb over divider and potty on other side if you keep papers in other side and blankets on their sleeping side.

We bought melamine which is a smooth coat of white and is non porous and wipes clean with one swipe.

This box will keep pups for 12 weeks or longer. I attach an exercise pen to the end, and they can run and play when older, jump back in and go potty or go in and sleep.

My idea is easy on me, the bitch and the pups.

It is screwed together and today we just took it down. I love it and wouldn’t use any other kind.

Pools are fine with newborns but what do you do when they start climbing out? Put the exercise pen around it.

Breeder/Exhibitor Ed, Breeding/Genetics

written & submitted by Kathryn Zerkel

- All reputable breeders have a zillion questions to ask why you chose their breed and why you want a puppy.

- They belong to at least one of the breed clubs and have a code of ethics to follow.

- They only breed a bitch once a year, if that often, and they do not breed them until at least 2 years of age.

- They make sure dog and bitch are both health tested for everything possible within that breed.

- They show their dogs and can tell you what they are striving for in their breeding program.

KNOWING WHEN TO RUN AWAY FROM A BREEDER:

- If credit cards are accepted RUN AWAY.

- If they have many litters a year RUN AWAY.

- If they say their breeding dogs have no problems therefore need no testing RUN AWAY.

- If they have several different breeds RUN AWAY.

And remember to be VERY wary of those that advertise champion backgrounds, yet when you look at the pedigree the champions are several generations back.

Breeder/Exhibitor Ed, Breeding/Genetics

written and submitted by Bill Garnett

Back in December, I was watching the confirmation hearings for Dr. Robert Gates regarding his becoming the next Secretary of Defence for the United States. During that hearing, a chord was struck, or if you will, a question was asked, and I paraphrase, “When does one stop thinking of their own accomplishments and center their concerns around the well-being of those they serve, protect and promote?” At that point, I couldn’t help but reflect on the words of our late President John F. Kennedy when he said, “ask not what your country can do for you . . . ask what you can do for your country.” At the risk of being overly dramatic, but also being as serious as I can be, a question arose in my mind. As Doberman fanciers when do we begin to think of the Doberman in terms of . . . not what the Breed can do for us . . . but what we can do for the Breed? As I began to dwell on that sentiment, I thought of myself and reminisced about the path that I had taken regarding my involvement in the sport of pure bred dogs and Dobermans in particular. I thought of how that involvement not only affected me, but in the long run, how had it affected the Doberman and its heritage . . . if at all.

As a young college student attending my first dog show in Richmond, Virginia, I was drawn to the Doberman ring. With its magnificent presence, beauty, grace and athleticism, it was only natural, being somewhat of a hot shot athlete, that I would find the Doberman to be my kind of dog. Not too long after that, I purchased a back yard pet named Max, and so began almost a half century love affair between me and the Doberman Pinscher. According to a “local expert”, Max was show-able, whatever that meant, so I entered him in a few shows in the American Bred class. My reasoning for entering him in the American Bred class was that I had purchased Max in America. That tells you how much I knew in those early days. However, being of a very competitive nature, I found the dog show ring to be right up my alley, and it helped that Max even won a class or two which peaked my enthusiasm even more.