Q&A

[vc_row][vc_column width=”5/6″][vc_column_text][dwqa-list-questions][/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/6″][vc_wp_categories title=”Article Categories” options=”count,hierarchical”][/vc_column][/vc_row]

[vc_row][vc_column width=”5/6″][vc_column_text][dwqa-list-questions][/vc_column_text][/vc_column][vc_column width=”1/6″][vc_wp_categories title=”Article Categories” options=”count,hierarchical”][/vc_column][/vc_row]

Judith Doniere, daughter of the late Clarence and Mary Cotter, died peacefully in her Las Vegas home following a three year battle with ovarian cancer.

Judy was born into a family who loved all animals starting with exotic animals she and her family raised for the Toledo Ohio Zoo. It was common to see baby chimps, lions, tigers, cougars, wolves, and leopards running around her childhood home. Judy also worked at the zoo cleaning cages and caring for animals. She was a horse lover owning 5 while raising her children, attending dog shows and later becoming a prominent AKC dog show Judge.

Judy and her husband Pat (deceased 2003) traveled the United States and many foreign countries for over 40 years during their careers as judges and still working various jobs in the secular world, Judy in Sales and Pat owning a heating and air conditioning company. Together they received the life time achievement award from the Doberman Pinscher Club of America, for their many years of service to various dog breeds and being authorities in the sport.

Judy was strong minded and determined to live with cancer if she could not live without it. She would schedule her chemo treatments around her dog show assignments. Her caring doctors, Dr. Cheryl Brewer – oncologist, ob gyn, surgeon, and Dr. Spirtos UNV, family and dog lovers encouraged her and helped her cope with the disease.

JuD went home after 7 weeks in Sunrise Hospital following her last surgery. She was under the care of Creekside Hospice who were loving and very attentive, especially in pain control.

Judy will be missed by her 4 children, 9 grandchildren and 7 great grandchildren, 3 sisters and 2 brothers.

Ask breeders questions about the health not only of the sire and dam, but of their siblings and parents, if known. How long did they live? What kind of surgeries have they had?

More information about finding the right Doberman for you may be obtained at:

(Learning is a process, not an event. An effective teaching experience combines the written and the interactive, refined by live observation.

As chairman of the DPCA Judges Education Committee I have a responsibility to inform the fancy of, in lay terms, how a judge interprets the Standard to select a winning Dobe.

I think it is important each fancier take the time to read the official Standard for the Doberman Pinscher. The Standard is available on the AKC and DPCA web sites.)

The judge’s first impression is the overall dog. Our Doberman handlers are some of the best in the world. They can make almost any dog look perfect in a stack, even to an experienced judge. The judge has only two and a half minutes to look at each dog so the well-presented dog has the advantage. Look for a square dog of medium size that is balanced. Does he have as much leg as depth of body? Is he deep to the elbows? Do his front angles match his rear angles? Is the length of the neck in proportion to the body and the head? Does his head look long but is it in proportion to the rest of the dog? Does he have heavy bone? Determine if the dog is powerful, elegant, alert, determined, muscular, and noble and is he compactly built. Many dogs have longer underlines than toplines. This can be caused by a straight upper arm which may cause a dog to look longer in length (more rectangular) than he actually is.

Having finished the initial observation, move the dogs in a group. Is anyone limping? Search for a fluid, powerful efficient gait that is balanced. Balance is very important and means that the gait generated by the rear drive is compatible with an equally angulated front to produce enough reach so the rear foot lands in the same spot as the front foot of the opposite side. Is the topline straight and smooth and does it hold while gaiting. Does the dog appear square or is it long in back or short in leg? Does it lack body? Check the tail carriage, it should be only slightly above the horizontal. Is the gaiting carriage proud?

Next is the individual examination where condition, attitude and show training come into play. Now is the time to reconfirm your initial side view impression with the overall dog. Approach the front; look at the head, breadth and depth of chest, and size and color of markings. Are the legs muscular and sinewy with heavy bone? Are the feet cat like? Place the head between your hands and look at expression. Is he stable, alert and confident? Feel the underjaw. Is the line from the skull to the muzzle unbroken and is it wedge shaped? Note the eyes for correct placement, shape, color and size. Are the ears set high? Is the skull too wide or too narrow, or just right? Looking from the side, view parallel planes and check for a slight stop, and depth of muzzle. Is the muzzle strong? Common deviations are snippy, pointy muzzles lacking underjaw, narrow heads that are not wedge shaped and round and/or light eyes.

The hands on examination is next. Check for muscle tone, placement and width of shoulders, snugness of elbows to body, and coat texture. Then, look at the rear, checking turn of stifle, equal length of upper and lower thigh, slightly rounded muscular croup, perpendicular hocks, and tailset. Look for a muscular rear, both on the inside and the outside of the legs, with parallel hocks set wide enough, where the front feet are seen just inside the rear feet. Is the rear cow hocked or bowed? Is the width of the hips equal to the width of the rib cage and shoulders? Is the dog slab sided (lack of rib spring) or barrel ribbed (too wide)? Are pasterns firm and almost perpendicular to the ground? Common deviations would be: shoulders that are set too far forward, straight shoulders, short upper arms, straight upper arms, lack of angulation – front or rear, long lower thigh, flat croup, high tail set, long loin, and lack of muscle in the upper thigh either on the inside or outside, as well as lack of muscle on the lower thigh.

The handler shows the mouth, or, if necessary, the judge opens the mouth. Count the teeth in groups, noting 42 correctly placed, strongly developed, white, teeth. The first group is the six incisors, the next group is the four canines (2 on each side, 1 upper, 1 lower) followed by the four premolars on the bottom and top of each side and the final group is the two top molars and three molars on the bottom of each side. Four or more missing teeth are a disqualification. The bite is checked. It should be a true scissors bite. Check to see if the bite is level, over or undershot. Overshot more than 3/16 inch and undershot more than 1/8 inch are disqualifications. Deviations are level bites, extra premolars, missing incisors, premolars and/or back molars, and poor occlusion.

Ask the handler to move the dog down and back on a loose lead, at a moderate pace. Watch the dog going around assessing side movement. Coming and going check for legs moving in a straight line. In the sound mover, the front legs are an extension of the shoulder and gradually converge towards the center as speed increases. Common deviations are moving too wide in front, too close in rear, side-winding, paddling, high stepping, loose elbows, flipping pasterns, and other inefficient gaits that prevent the dog from tireless, ground covering movement. Many times dogs do not move as well as they could because they are not in condition or are poorly trained. It is also difficult to evaluate a dog that is looking up at his handler or sniffing the ground. The well-conditioned and trained dog moves in a straight line down and back, with drive and determination. Many handlers cause their dogs to move inefficiently by using a tight lead. The dog on a loose lead moves best.

At the end of the down and back ask the handler to show the dog in a free stacked. Here is where the temperament and attitude meet with the judge’s toughest evaluation. In the free stack look for a dog who stands his ground confidently. As the judge moves around him he may flick an ear or turn his head to see who is there, but he remains calm and composed. The dog should be aware of the judge moving around him and not just fixed on the liver. At this point, you can see where he naturally puts his feet. The true topline, tailset, head and neck carriage are apparent. Put a lot of stock in dogs that exude energy, are alert and show fearlessness.

Upon completion of individual examinations, the final group is determined. If the class is eight or more, place the dogs in their tentative order. Then you move the class once or twice around and watch them stop. At this point, you can do another down and back with the top contenders, watching carefully how they stop. Then place the class. Many times exhibitors ask why the last down and back didn’t result in a change of placement. The reason is, in the final analysis, he moves well enough to confirm his win.

This is what a judge does in two and a half minutes in front of a partisan audience. No one ever said it was easy. Common sense indicates all judges have a specialty breed. All knowledge of other breeds is acquired knowledge, sometimes in the face of angry exhibitors.

What does this say about exhibiting purebred dogs? There is no perfect dog. The one picked at a particular show is the dog closest to the standard the judge has pictured in his mind of the ideal Doberman. A judge can only judge what is presented to him. The exhibitor must be patient. If he has a good dog, his time will come.

General Appearance | Head | Neck, Topline and Body and Tail | Forequarters | Hindquarters | Forequarters and Hindquarters together | Gait | Temperament

1999–A

This standard doesn’t have a section devoted to temperament but they do cover this in the General Appearance section.

A well built and muscular dog, not plump and massive and not like a greyhound. His appearance must denotes quickness, strength and endurance. Temperament lively and ardent. He is courageous and will not run away from anything. Devoted to master and in defending him shows the courage of a lion. He gets along with other dogs; not vicious or disloyal; faithful and watchful and a superior destroyer of animals of prey.

1901–B

Characteristics: Watchful, loyal and devoted, intelligent and not vicious, however, nevertheless sharp; working equally well on water and on land; superior destroyer of animals of prey.

In this standard temperament is also addressed in the general appearance section which says: Temperament lively and ardent. He is courageous and will not run away from anything. Devoted to master and in defending him shows the courage of a lion. He gets along with other dogs; not vicious or disloyal; faithful and watchful and a superior destroyer of animals of prey. His eyes show intelligence and resolution.

1901–C

Characteristics: Ideal police dog. Watchful, loyal, devoted, intelligent; working equally well on water and on land; superior destroyer of animals of prey. good companion on the hunt. Good protector of his master; gets along with other dogs, however, when attacked, show no fear.

Temperament is also mentioned in the General Appearance section which says: His temperament is lively and ardent. His eyes show intelligence and resolution.

1920

Qualities: Pleasant in manner and character. Faithful, fearless, attentive and a reliable watch dog. Sure defender of his master, distrustful towards strangers, possessing conspicuous power of comprehension and great capability of training. In consequence of his characteristics, physical beauty and attractive size, an ideal house dog escort.

Temperament is also mentioned in the General Appearance section which says: Temperament lively and ardent, the eye expressing intelligence and resolution.

1925

Qualities: The Doberman pinscher is a loyal, fearless, courageous and extremely watchful dog who possesses very much a natural sharpness and high intelligence. Despite his fiery temperament he is very obedient and easily trained. He has a most excellent sense of smell, is of great endurance and the ideal of a house dog, companion and protector.

Faults: a shy, cowardly and nervous character.

Temperament characteristics are talked about in the General Appearance section in this standard too: Elegant in appearance, of proud carriage and great nobility, manifesting by its bearing a wide-awake vivacious personality. Temperament energetic, watchful, determined and alert; loyal and obedient, fearless and aggressive.

1935

Conformation and General Appearance: Elegant in appearance, of proud carriage and great nobility, manifesting by its bearing a wide-awake vivacious personality. Temperament energetic, watchful, determined and alert; loyal and obedient, fearless and aggressive.

Faults: failure to manifest any of the temperament characteristics.

SCALE OF POINTS

temperament, expression and nobility……………………8

1942

Conformation and General Appearance: Elegant in appearance, of proud carriage, reflecting great nobility and temperament. Energetic, watchful, determined, and alert, fearless, loyal and obedient.

Faults: Lack of nobility and temperament. Shyness. Viciousness

1948

Conformation and General Appearance: Elegant in appearance, of proud carriage, reflecting great nobility and temperament. Energetic, watchful,determined, alert, fearless, loyal and obedient.

Disqualifying Faults: Shyness, viciousness.

Shyness: A dog shall be judge fundamentally shy if, refusing to stand for examination, it shrinks away from the judge; if it fears an approach from the rear; it shy from sudden and unusual noises to a marked degree. Viciousness: A dog that attacks or attempts to attack, the judge or its handler is definitely vicious. An aggressive or belligerent attitude towards other dogs shall not be deemed viciousness.

SCALE OF POINTS

temperament, expression and nobility……………………8

1969

Conformation and General Appearance: Elegant in appearance, of proud carriage, reflecting great nobility and temperament. Energetic, watchful, determined, alert, fearless, loyal and obedient.

The judge shall dismiss from the ring any shy or vicious Doberman.

Shyness: A dog shall be judged fundamentally shy if, refusing to stand for examination, it shrinks away from the judge; if it fears an approach from the rear; if it shies at sudden and unusual noises to a marked degree.

Viciousness: A dog that attacks or attempts to attack either the judge or its handler, is definitely vicious. An aggressive or belligerent attitude towards other dogs shall not be deemed viciousness.

1982/1990

Adopted by the DPCA and approved by the AKC on

Source: American Kennel club. (Note: The only change in 1982 to the standard approved in 1969 was the addition of a disqualifying fault for dogs “Not of an allowed color.” The standard was reformatted only and no descriptions were changed in 1990.)

Temperament: energetic, watchful, alert, fearless, loyal and obedient. The judge shall dismiss from the ring any shy or vicious Doberman.

Shyness: A dog shall be judged fundamentally shy if, refusing to stand for examination, it shrinks away from the judge; if it fears an approach from the rear; if it shies at sudden and unusual noises to a marked degree.

Viciousness: A dog that attacks or attempts to attack either the judge or its handler, is definitely vicious. An aggressive or belligerent attitude towards other dogs shall not be deemed viciousness.

In this standard too the temperament characteristics are talked about in the General Appearance section which says: Elegant in appearance, of proud carriage, reflecting great nobility and temperament. Energetic, watchful,determined, alert, fearless, loyal and obedient.

FAULTS: The foregoing description is that of the ideal Doberman Pinscher. any deviation from the above described dog must be penalized to the extent of the deviation.

This is what our history of the standards say about the Doberman Pinscher temperament and character. Most all of the standards mention these important traits in two places. Our present standard mentions temperament in two places. To me by doing this, it tells us that the temperament of our breed is paramount.

Let’s talk about the temperament and the characteristics of the Doberman Pinscher. Our forefathers sure had a great dog in mind, didn’t they? I can see that from the very beginning, can you?

Marj

Reproduced by permission from “Dogs in Review”, authored by Bo BengtsonJanuary 2012 issue of “Dogs in Review”

You have no doubt heard about the stud dog who was so valuable that he was not allowed to breed bitches except through artificial insemination. It turned out later that he was not capable of breeding on his own at all, and neither were most of his sons. There was also a famous bitch who was not allowed to whelp naturally, because who knows what damage that could have done, so she gave birth to her first litter by C-section — then to three more, also via C-section. And, big surprise, some of her daughters proved unable to whelp naturally. And there was the Best in Show winner who was so precious her owners did an embryo transfer, so their beautiful bitch would be spared the travails of pregnancy — which, of course, means nobody knows what kind of mother she would have been.

When you mess with Mother Nature, as we dog breeders have been doing with varying degrees of success for 150 years now, eventually there’s a price to pay. I seem to hear more often than I used to about dogs who are not able to breed naturally, bitches who have difficult whelpings and don’t know the basics of motherhood. With the advances of veterinary care, somehow there are usually live puppies anyway in the end… but at what price for the future of the species?

It was refreshing to read that one (but only one) of the seven finalists interviewed for AKC’s “Breeder of the Year” award mentioned a strong reproductive drive and good maternal instincts among the prime considerations when selecting breeding stock. How common are those priorities among show people these days, though? I overheard a couple of successful breeders at a show extolling the wonders of C-sections recently: just let the veterinarian take care of it! Much more practical than a messy natural whelping… but it’s not exactly how things were meant to be, is it?

We’re all a little guilty, I guess: we love our dogs, want to make things easy for them, are eager to make sure that even the weakest puppy of the litter survives. Who knows, after endless efforts that puppy may actually make it, grow up to become a beautiful champion — and continue to reproduce the species, with or without any immediate damage done to its breed.

No, I’m not advocating a return to the days of rough natural selection when a breeder basically peeked into the kennel and thought, “Hmm… Looks like Lizzie had her pups. We’ll see in a couple of weeks what she got!” I certainly don’t have the stomach to just “bucket” a weak puppy. But I am wondering if in the long run we’re doing ourselves and our dogs a disservice by not focusing more on their ability to reproduce naturally, with a minimum of human interference. There are no Best in Show awards for this, but perhaps there ought to be.

Oh, for the record: those dogs I mentioned at the beginning of this column are purely apocryphal: they don’t exist. Their counterparts do, though, and I bet you know at least some of them…

The term “albinism” encompasses a wide range of traits, all of which result from problems with pigment production or distribution. So far, more than 60 different mutations have been isolated from many different species. Many of these mutations and their subsequent effects have been found to be identical in both humans and non-humans. Since the basic mechanisms for pigment production are nearly identical across all mammals, most data gathered from one species can easily be applied to other species.

Pigment-melanin- is produced through a series of chemical reactions which are made possible by the action of various enzymes in the body. The same general process occurs in all mammals, both human and non-human. For all mammals the most important enzyme in the production of melanin is tyrosinase. The enzyme tyrosinase encoded by the gene Tyr is usually referred to in veterinary medicine as C.

The “classic” type of albinism is known as OCA1, Oculocutaneous Albinism, type 1. OCA1 involves a mutation in the gene which produces tyrosinase . Albinism always effects vision. Dobermans of the four accepted colors do not have these vision problems. The vision problems in albinism result from abnormal development of the retina (due to lack of normal levels of pigment during development) and abnormal patterns of nerve connections between the eye and the brain. The optic nerves are misrouted to the brain. The CERF examination, commonly used to detect congenital ocular defects in dogs will not detect several of the visual problems associated with albinism. CERF does detect cataracts, progressive retinal atrophy, or persistent pupillary membranes, it does not detect near-sightedness, far –sightedness, astigmatism,loss of depth-perception and the optic nerve abnormalities common to albinos. Since pupillary dilation makes all dogs photosensitive, this means that CERF examinations will not detect photosensitivity either. Obviously, visual deficits would be a serious handicap for a working breed dog. Also, the poor vision suffered by albinos may be a partial explanation for the aggressive and /or fearful behaviors often reported in albino Dobermans. There have been multiple reports of photosensitive/photophobia from owners of albinistic Dobermans, as well as repots of extreme nearsightedness (such as an inability to recognize family members from across a room and inability to chase a ball) and severe lack of depth perception (such as difficulty climbing stairs or with problems falling off of a porch ). Photophobia in these dogs was also confirmed by ophthalmogic exam.

More than 50 Tyr mutations have been identified in humans. They are in general divided into two subtypes, Type 1A having no tyrosinase activity whatever, and no melanin pigmentation, while type 1B(OCA1B) has greatly reduced tyrosinase activity, but with some melanization. Classical albinos or “complete” albinos are tyrosinase negative and “partial” albinos are tyrosinase positive. Partial albinos ARE still albinos.

The albinistic syndrome may accompany a wide range of health problems. Some types of albinism affect the immune system, liver, or clotting ability ( eg Hermansky Pudlak Syndrome- abnormal platelets that lead to mild bleeding), and others may cause other physiological abnormalities such as defects in the kidneys or thymus, inner ear defects and neurological abnormalities just to name a few. Albinism in general predisposes animals to skin cancer as well as photosensitivity/photophobia. Albinisim is a deleterious mutation which effects the whole body.

All current evidence supports the conclusion that “white” Dobermans are indeed suffering from some type of albinism. Like other “tyrosinase-positive or “partial “ albinos, they have unpigmented skin and eyes. Like other albinos, the trait is inherited as a simple recessive trait. Like several other types of alblinism, they appear to have abnormal melanosomes. In fact, nationally recognized geneticists agree that these dogs are albino. Several experts in genetics, alblinism, pathology, and opthamology have agreed these dogs appear to be albinos, including G.A. Padgett, D.F. Patterson,

M.F.C. Ladd, W.S. Oetting, J.P. Scott, and David Prieur. Not a single expert in any of these fields has reached any other conclusion.

For example, Dr. Oetting has stated “It sounds as if the dogs do indeed have albinism…These dogs sound like they have OCA1 resulting from mutations of the tyrosinase gene, a major gene in pigment formation”.

G.A. Padgett, DVM, Professor of Pathology, has stated “I would agree with Dr Patterson’s suggestions (1982) that this is probably a mutation in the C series. I believe it is an albino, although not the classical pink-eyed tyrosine negative animal which we associate with this term. They are phototypic, and I believe there is little disagreement with this statement”. After examination of hairs , Dr Padgett says “ The white Doberman is not a normal white.”. Dr. Padgett also lists albino Dobermans as partial albinos in his book Control of Canine Genetic Diseases.

David J Prieur,DVM, PhD. Of the WSU Dept. of Veterinary Microbiology and Pathology, has stated “Several years ago I expressed my concern regarding the breeding of “white” Doberman Pinscher dogs. I expressed the opinion that the gene for the white coat was a deleterious gene and that the Doberman Pinscher breed would be better served by not incorporating this gene into the gene pool of the breed. Although these ‘white’ Dobermans have been shown not to be true albinos, they are tyrosine- positive albinoids with a severe reduction of melanin in oculocutaneous structures. There have been numerous defects described in animals of other species with genes of this type…I am unaware of any information, published or presented, since I originally expressed my concerns, which would lead me to believe that this gene is not deleterious.”

Dr. M.F.C. Ladd, a British veterinary geneticist, has stated “Albinism means the complete absence of melanin pigment (Searle,1981) . If one accepts this view, then dogs such as the white Dobermanns with blue eyes , can be termed albinos….Unless much more evidence is forth coming, I feel that the white Dobermann should be looked upon as abnormality, known to exist and hoped to be avoided.

J.P. Scott, PhD., a geneticist at Bowling Green State University, has stated; “Photophobia would constitute somewhat of a handicap to a working dog”, and “Something must be done” . I realize that most breeders are responsible, selecting strains that seem good. But once an undesirable trait enters a breed, it is not an easy thing to eliminate.

The Albino Dobermans are not acceptable for they possess a deleterious gene that causes ocular changes as well as affecting the immune system, and possessing neurological disorders. Albinism predisposes the animal to skin cancer as well as photosensitivity/photophobia. The mission of the parent club is to protect the integrity, health and function of the breed and not to promote the breeding of unacceptable specimens.

The AKC should honor this and help protect the breed by limiting the albino and factored dogs with a mandatory limited registration.

On November 10, two back and rust parents produced 11 black and rust puppies and one female mutant albino with translucent blue eyes, pink nose, eye rims and pads. Padula’s Queen Sheba. All albinos are descendents from this dog.

Registration was sent into AKC with albino written in the color section.The Blue slip was returned explaining that albino is not a color. Photgr

aphs were requested and the registration review committee said the female was white. The first albino was registered without parent club consultation. Approximately 6500 descendants have been registered over the past 24 years, roughly 5000 or so are carriers of the albinistic trait.

DPCA asked the AKC to investigate the albino. AKC determined they are purebred.

AKC approved DPCA amendment to our standard: Disqualifying fault: Dogs not an allowed color.

DPCA bought two albino bitches for breeding studies. These dogs and their Offspring showed: Photosensitivity, hyperactive fear biters, and prone to solar skin damage.

AKC agreed to provide specialized tracking for albino and albino-factored Dobermans through special registration numbers thus creating the “z” list.

All descendants of Shebah’s parents born since 1996 have carried registration numbers starting with “wz”.

The American Kennel Club

260 Madison Avenue

New York, NY 10010-1609

Mr. David C. Merriam

Chairman of The Board

Mr. James P. Crowley

Executive Secretary

Dear Sirs,

As the representative of the Doberman Pinscher Club of America I am writing you to let you know our concerns and desires for the handling of the white albino Doberman situation. The mission of the DPCA is to protect the integrity, purity , health and function of the breed.

First of all we appreciate the effort of the AKC in setting up a tracking system for the albino dogs as well as the carriers of the albinoid gene. Unfortunately this is only half the battle in the survival of the integrity of our breed. The only way we can cleanse the breed from this deleterious mutation gene is to not allow these animals to be bred. By implementing both the tracking system and a restricted registration, only then, can the breed maintain its purity. The elimination of this gene with its associated detrimental health problems would help maintain the integrity of our breed.

We would be happy to meet with you or the Board for further discussions at the AKC to answer any questions you might have. Thank you for your consideration.

Sincerely yours,

May S Jacobson, Ph.D.

Associate in Medicine

Children’s Hospital Boston

Harvard Medical School

Holly Schorr has been involved with owning, showing (Obedience and Conformation), breeding and training Doberman Pinschers for almost 38 years. Together with husband, Steve, under the Kennel name of PennyLane Dobermans, they have shown and bred over 50 Champions, multi Best In Show and Best In Specialty Show winners in two countries with many obedience and tracking titles also. Holly teaches Obedience and Conformation for all breeds.

In the early 1970s, Miniature Schnauzer breeders embarked on a program unprecedented and unduplicated in any popular breed: to eliminate the genetic defect that caused juvenile cataracts. Research had established that juvenile cataracts (CJC) were transmitted as autosomal recessive with complete penetrance and were present at birth. Early diagnosis permitted the use of test-breeding, sanctioned by the national breed clubs, in which certified affected dogs were paired with mates whose status was unknown. A litter of normal eyed puppies was known to generate a mathematical probability that the tested dog was clear (the more normals, the better his or her odds), while the diagnosis of a single affected puppy proved the dog a carrier.

There is no argument that the program met its goals. A breed with an estimated 40% carrier rate emerged from two decades of test breeding with show lines cleared of the defect. It was a spectacularly successful example of how a breeding community can come together to eradicate a defect… and cause devastating damage to the gene pool.

It has been written that, as a result of the process to eliminate CJC, over 200 American Champions were retired from breeding. Important kennels quietly closed up shop, taking distinct family branches with them, and bitches were sent exclusively to test-bred stud dogs. It was a lonely time for an untested male.

Around the same time as CJC was defeated, PRA made its entrance. In a few short years, several leading sires were revealed to be carriers and retired. There was no test-breeding program for this late onset defect, so it became a lonely time for the stud dog or bitch with a carrier ancestor. The gene pool contracted again.

Had this been the end of the troubles, there may have been time to pause and reflect on what was happening in the big picture, but this was not to be. A novel defect appeared on the scene – a muscular disorder called myotonia congenita. This problem found a solution in short order as a DNA test was developed, allowing breeders to identify carriers with a simple blood test. Those were retired, too. My choice of the word “retired” has, of course, been deliberately inappropriate here. In the world of dogs, “retired” is usually a euphemism for “sterilized”. As a device for preventing genetic defects, it must rate as one of the most destructive practices ever employed.

In a sensible dog world, quality carriers of genetic disease might be pulled from widespread use, but they’d come out of “retirement” for special occasions (i.e., for research breedings and/or the general advancement and preservation of rarer family lines). However, the dog fancy – and, by extension, breed clubs – have never been famous for our ability to apply knowledge sensibly. There is a common caution against throwing the baby out with the bathwater. In purebred dogs, there is a tendency to gather up the siblings, cousins and parents and throw them into the dustbin as well. We “improve” our breeds by killing them off one family branch at a time.

When I first began breeding nearly 30 years ago, I accepted the conventional wisdom that largely prevails to this day – that genetic defects are the exception, that carriers should be removed from the gene pool and that health is more important than beauty. But, as John Maynard Keynes said: “When somebody persuades me that I am wrong, I change my mind. What do you do?”

A few years ago, some bright bulb at the Canadian Kennel Club launched a grand scheme to create a Code of Ethics. One of the rules proposed for this set of stone tablets was “Thou shalt not breed a carrier”. I recall writing to one of the Board members at the time to congratulate the CKC for devising an edict that would result in the immediate eradication of a number of breeds. For there are breeds today in which every single member is not merely a carrier, all or nearly all are affected with a genetic defect. The peculiar nature of Dalmatian urine chemistry is the most famous example.

Even in breeds with more moderate disease rates, the policy would have eventually resulted in genetic collapse and extinction. That’s because every normal living being is thought to carry in the range of 5 disease mutations in their DNA. In breeds with few founders and extreme bottleneck events, that average may be much higher. As molecular genetics digs into the DNA of our four footed friends, it is revealing gene frequencies that are nothing short of staggering in some breeds. In English Springer Spaniels, for example, a mutation that elevates the risk of PRA has been identified and a DNA test developed at the University of Missouri-Columbia. Of the dogs tested, only 20% have been found to be clear of the gene while over 40% tested as affected. Dobermans have similar carrier rates for the bleeding disorder, vWD.

The purpose of this article is not to cover the ground of nuts and bolts genetics. There’s simply not enough space and I don’t have the right letters after my name. There are many good texts available that cover the science, as well as a number of authoritative Internet sources. It is recommended that you seek the most recent material you can find as many of the popular canine genetics books of the past are now obsolete.

What I hope to provoke is an examination of some of our traditionally held beliefs. “Thou shalt not breed a carrier” served us well enough when diagnostics were primitive, most carriers escaped detection, and conditions now known to be inherited were dismissed as environmental or simple bad luck. This is no longer the case.

Unfortunately, a little knowledge can be dangerous. The discovery of extreme carrier rates in a breed has the potential to overwhelm breeders who have always held that their primary goal was to produce healthy dogs. It’s depressing to think of how many aspiring breeders accepted as an article of faith that quality foundation stock, good intentions and careful testing would result in good health – only to fail. They’d start over, fail again, become discouraged and move out of the sport. Now we know why.

The bottom line is that much of what we thought was wrong. Now, for the sake of our breeds, we need to change our minds. It is no longer a question of “eliminating” gene defects from a breed. We can only ask which ones, how quickly and should we even try? For this reason, it is imperative that breed clubs take the lead and reform outdated notions about “ethical” breeding practices and the advisability of “retiring” animals before they can leave positive contributions to the gene pool.

One of the most important factors in maintaining a healthy breed population is preserving genetic diversity. Genetic diversity is important for survival and adaptability within species, but dog breeds are not species. They are purpose-bred populations that have undergone selection for specific traits or behaviours. It is not enough to simply survive; they have a job to do. Nonetheless, within closed gene pools, genetic diversity is central to infectious disease resistance and the availability of normal alleles when mutations arise.

There is little disagreement on that point, but there can be great disagreement on the best means to achieve it. One camp believes in outcrossing, de-emphasis of “show ring” traits and performance standards, and even selected infusions of other breeds. Another camp holds that a healthy diversity of successful breeders who work to preserve and develop distinct family lines is the best way to preserve genetic choice. I happen to belong to the latter.

Before one begins, however, one must first define “successful”. Or rather, one must understand how success is defined in any breed. It is not a matter of interpretation; it is a matter of record.

A few years after I began showing and breeding Miniature Schnauzers, I realized that no historical archives existed for champion producers in Canada, in

the way they have always been catalogued in the US. So, I began gathering the data from old CKC stud books and issues of Dogs In Canada, starting with the first recorded champion in 1933.

Somewhere in the middle of the project, I had an epiphany. Everything that I had been told to believe was wrong: Health is not more important than beauty. Beauty is more important than health.

Next Issue: It isn’t important that we all do the right thing, it is only important that we don’t all do the wrong thing. Forcing everyone to do the same thing risks forcing everyone to do the wrong thing.

Somewhere in the middle of the project, I had an epiphany. Everything that I had been told to believe was wrong. Health was not more important than beauty…beauty was more important than health.

As I recorded the names of champion offspring of those dogs of the past, I began to notice patterns. Kennels would emerge, win well for a time, and then fade away upon the arrival of new competition with better winning stock. The majority of sires and dams that had produced multiple champions in their day were virtually absent in modern show pedigrees. Their lines had, for all intents and purposes, become extinct.

As it turned out, the most reliable asset a line could possess wasn’t the ability to produce large litters without assistance, live to a ripe old age, or pass a series of health clearances. It was that someone had to want to breed them, and then actually breed to them.

Breeding dogs for the competitive arena is labour intensive and expensive. With little chance of profit, the motivations are largely esoteric – goal attainment, pride in performance, thrill of competition, appreciation of beauty and form. Bloodlines that fulfill these ambitions tend to grow and expand their share of the gene pool, while those that don’t, wither away or are relegated to producing puppies for the pet market. It’s not to say that winning is the only thing that matters, but it’s fair to say that nothing else matters as much. For, while gene defects may slow the expansion of a winning family into other lines or force it in a new direction, ugly is fatal.

Each time we are confronted with genetic disease, whether it be in the role of individual breeder, mentor or breed club, it is this “human factor” that must always remain front and center.

Programs designed to reduce defects in a breed or a family, while absolutely necessary for long-term health and control of gene frequencies, must never be permitted to subordinate the quality of animals, or the ability of individual breeders to achieve their aims. Without quality, the line will not survive future selection pressures. Without quality, breeders will find themselves hard pressed to continue.

It is not good enough to promise a light at the end of the tunnel. Those lights must remain on along the route so that individuals are reminded that there is more to breeding dogs than avoiding the bad.

That of course, doesn’t grant us license to ignore our problems, or worse yet, to conceal information. Without open and frank disclosures, the very risk reduction strategies that allow breeders to manage disease frequency are impossible.

The first priority for breed clubs is to update our old strategies and accept that genetic disease is a normal part of the makeup of good dogs. While normalizing defects may seem heresy to some, it is only through accepting there is no such thing as a “clear” dog that modern breeding programs will survive the wave of information that is beginning to come ashore. As previously mentioned, new DNA tests are uncovering gene frequencies in some breeds that have the potential to result in the total collapse of gene pools, if efforts at reduction are not carried out with extreme caution. It’s imperative that breed clubs get out ahead of this, and begin the re-education process now.

Of course, talking about transformation is easy; putting it into practice at the kennel level, much harder.

“I just got back from the clinic. I don’t know what to do.”

Anyone who has found themselves slumped in a chair with a CERF form in one hand and a drink in the other knows the feeling.

For a disturbingly large segment of the fancy, the only “ethical” response is to search for a sword to fling one’s breeding program upon – the more publicly, the better. Not because it’s the logical, rational thing to do, but so that they may hold themselves up as morally superior. Every breed club has influential members who hold these well-intentioned, but destructive views. It’s time to confront them with reason.

Defective genes have been part of the makeup of breeds for scores of generations. Most became widespread long before veterinary science had the ability to identify, diagnose and treat them, and those breeds managed to survive. Your breeding program can survive, too – but it’s up to you.

There is no need to cure Rome in a day. Nor is there any need to sacrifice the best animals in a breeding program to avoid criticism from the uninformed and just plain vindictive among your peers. Pleasing your enemies does not turn them into friends.

The first step, particularly for the novice breeder who is facing genetic disease for the first time, is to give yourself breathing room. Take no action until your emotions are under control. Go to the field trial, continue your coat work, enter the shows you had planned. Your kennel’s participation in the competitive arena should not change because you’ve had a bad diagnosis – indeed, this is when you most need to remind yourself of the rewards that come from your involvement in dogs. Certainly, some exhibitors may beak and complain. Ignore them.

Take a few weeks to research the defect and your pedigrees. Ask yourself a list of questions designed to determine to what extent the defect can be tolerated in your breeding program, if it must be tolerated, and what impact you will allow it to have on future breeding plans.

1. Does the defect cause significant for pain or reduction in lifespan of the dog? Do affected animals pose a risk to others (aggression behaviors, etc.)? Do effective treatments exist? If chronic, is it difficult or expensive to diagnose or treat?

Generally, the more serious the effect on the dog’s well-being and the owner’s pocketbook, the less likely you or others will want to risk producing others who might suffer from it.

2. Is the problem common in your breed or the family line? Is it rare? Does it represent something new?

There may be nothing to gain from retiring a dog because he carries a gene that’s prevalent in the gene pool. Removing him won’t reduce the gene frequency, controlled breeding won’t increase it. It may be the “cost of doing business” in that line or breed until improved screening protocols come along. Learning to live with it may be the only choice available.

Conversely, the dog that carries a novel defect has the potential to transform a rare mutation into a common one. Such a dog is capable of raising gene frequencies and introducing disease into lines that are currently clear from it, so must be handled with discretion if bred.

3. Can it be diagnosed in a puppy, or does it show up after the dog is placed in a home, or has embarked on a breeding career?

The earlier a defect can be diagnosed, the easier it is to manage in a breeding program. The pain isn’t visited on buyers and the issue remains a “breeder’s problem”.

4. Is the mode of inheritance known?

The more one knows about the mode of inheritance, the easier it is to balance pedigrees and work around, or even eliminate a problem. (If not, don’t draw conclusions as to the genetic status of the parents and offspring. Some modes of inheritance are quite complex, and expression intermittent.)

When those questions have been considered, they must be placed into context:

1.

What is the quality of the affected/carrier animal? Does it possess outstanding virtues or is it just average? What does the rest of the health and genetic profile look like? Is it likely to produce puppies that are worth the effort?

2. Is the affected animal from a prosperous family line, or is it rare?

This may require digging deep into your pedigrees, as few modern breeders or even breed clubs are as aware of the originating lines of their breed as they should be. > Rare and distinct family lines may carry valuable alleles important to the genetic diversity and future health of the breed and their extinction should be avoided at all costs. Line preservation trumps genetic disease concerns in all but the most extreme cases. These are the dogs for which the “baby and bathwater” analogy was created.

So, let us return to our breeder’s CERF form, now that the drink is finished.

In this simplified example, the dog has been diagnosed with cataracts. Cataracts are fairly frequent in the breed. While some research is underway, no DNA test exists. Not much is known about the inheritance, other than it appears to be familial. Cataracts can result in complications and surgery, but most affected dogs live fairly normal lives despite them.

Now, what about the dog and her pedigree?

As you may have deduced, there is no one answer that fits all.

A) The bitch is from a popular line. She’s of good quality, but not exceptional. She has a normal-eyed half sister who is two years older. The breeder decides to spay her – there’s more where she came from.

B) The bitch is fabulous, with an impressive show career. She’s from a popular line, but has never been bred. The breeder chooses a complimentary sire of a line with low incidence of cataracts, with the goal of producing a daughter he can carry on with.

C) The bitch is the last daughter of a rare branch of the breed. She is of good quality and general health. The breeder decides to line breed her to a CERF normal sire who is well up in years, that compliments her type and fortifies her unique pedigree.

All have made rational decisions. Breeding the average bitch from a popular line isn’t likely to advance anyone’s interests. Spaying an exceptional bitch without ensuring she has a chance to pass on her virtues is not in the long-term interests of any breed. (Mediocre dogs carry disease genes, too!)

The breeder who goes on with an affected bitch from a threatened line also has his priorities straight. When in doubt, advance the line. A carrier son or daughter might some day produce puppies that test clear, but quality descendants must exist, or there will be nothing to test.

None of these strategies suggest that a dog with a serious genetic defect should be offered at public stud, or his puppies sold to prolific kennels. But between popular sire and sterilization is a very large middle ground in which dogs that are not suitable for wide use can still make a positive contribution.

As breeders, we have been entrusted with something very precious – a bitch line. Every time one of us fails to produce dogs of sufficient quality to carry it forward, we fail that trust. When we become lazy and indifferent about promoting our good dogs to others, we fail again. The daughter of the daughter fails to produce a daughter that carries on, another branch of the breed dies and the gene pool narrows a tiny bit more.

When managing genetic disease, there is seldom a “one size fits all” solution. Breed clubs need to recognize that individuals have different priorities and challenges, and accommodate this when issuing recommendations.

Most of all, we must recognize the absolute importance of the “human factor” in preserving families and advancing breeds. Breeders are most motivated when they are breeding for something – towards the good, not away from the bad. We need to acknowledge the power of beauty to inspire us, and pledge never to ask a colleague to give up on a dog or a line that they love in the pursuit of a goal that is unattainable – the disease-free breed.

And we must forgive each other’s mistakes, for despite our best breeding intentions, there will be many.

It’s not important that we all do the right thing – it’s only important that we don’t all do the wrong thing. When we force all breeders to do the same thing, we risk forcing all breeders to do the wrong thing.

As for those two hundred champions that were retired from my breed to eliminate a single gene? I often wonder where we could have been today if only a handful of the best had been bred one or two times more.

compiled by V. Cherie Holmes

The Doberman Pinscher is a compilation of many breeds. The following is a list of breeds thought to be the predecessors of the modern Doberman. These animals contributed to the Doberman over a period of 35 years.

The old German Shepherd dog:

These shepherd dogs were crossed with Pinschers to produce a Thuringer type butcher dog that was common in the area. In the early part of the 1870’s, it was told, Herr Dobermann crossed the progeny of a blue-grey Pinscher type bitch and a black and tan butchers dog, with a German Pinscher. This may be the first indication of the breeds used in the development of our breed.

The Butcher Dog, who was the ancestor of the Rottweiller as well as the Doberman, shows very strongly in this dog,

Graf Belling von Gronland, shown below.

At one of the first shows, in 1899, there were 12 Dobermans including the winner, Graf Belling, in a ring. It was said that those 12 dogs were so similar to Rottweilers that you could not tell the difference between a bad Rottweiler or a good Doberman, apart from the cropped ears!

The Beauceron : Their link to Dobermans can be made in that the Beauceron was brought to Prussia in 1806 with Napoleon’s army. The Beauceron, shown below at the turn of the century, were known to have interbred with the local dogs.

The German Pinscher:

The legacy of the German Pinscher addition is very little. It may be deemed that this addition was not a goal, but a stepping stone, and not as harmful as a breed with a more distinct type than the Doberman, would have been. The dilution of German Pinscher blood has been complete many years ago as this was not the direction the originators of the breed were wanting to go. The head, size, and body shape were not in our blueprint, and so were eliminated over time with selection.

In 1939, Herr Gruenig, (in his book, The Doberman Pinscher, 1939), said,” The German Pinscher contributed little to the head type. The Rottweiler, or old Butcher’s dog, sporting dogs, all added traits like heavy jowls, and thick skulls in which earlier specimens bear testimony.

In 1902, a Gordon Setter was crossed in, with the purpose of improving the coat color. As the short coat proved dominate, no harm was immediately seen. The color of the coat was not improved, but generations later, the long coat would show up, when the genes inadvertently were doubled.

This is a picture of 2 early dogs, circa 1899. The size of these early dogs were around 25 inches for males. The first standard was written in 1899, upon the formation of the first Doberman Club. As soon as this blueprint was set down, the breed changed rapidly into the dog we know today.

At the turn of the century , the Manchester Terrier was added. As the German Pinscher, Manchester Terrier, Rottweiler, and Beauceron are very similar in look, these crosses did not change the appearance of the turn of the century Doberman, as much as it enhanced it. Phillip Grunig stated in 1939, of the dogs of that period, “Under these circumstances it would be difficult to distinguish a coarse Doberman from a refined Rottweiler. It would be equally difficult to distinguish a small and delicate Doberman from a coarse German Pinscher, etc.”

The Doberman of today owes his present form to the many crosses done in the early years. Below is a picture of Fedor V. Arpath, born in 1906. This dog is 1/4 Manchester Terrier.

The Manchester was added to get the smooth, short coat that we desired. The hair is also very thick, with many hairs per square inch.

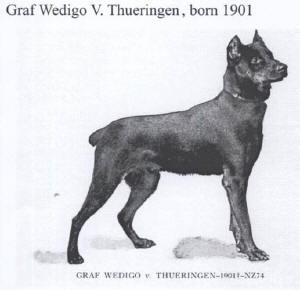

| Alarich v. Thueringen , born 1897, is an excellent example of what the breed was like at the turn of the century. |  |

|

Graf Wedigo V. Thuringen, born 1901 |

Greyhound:

A black Greyhound male from England was the sire of a bitch named Stella, a stud book entry in 1908.

|

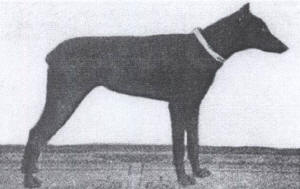

On the right is a picture of Stella’s daughter, Sybille, born in 1908. Sybille is 1/4 Greyhound. |

|

|

Rival’s Adonis, best of his day, 1914 ,and a great stride forward You can see that with the concentration of breeders and their dogs, the shape is already in sight. |

Doberman Pinscher Club Of America was formed in 1921, when the fanciers attending the Westminster show decided to band together to promote their then relatively unknown breed. The official German standard was adopted by the DPCA on Feb. 13, 1922.

Breeders, remember, you have been given, by your predecessors, the torch and a blueprint to follow. As the breed is only a little over 100 years old, it could be set back seriously in only a few generations of short-sightedness.

Judges must recognize that although our breed has many breeds in it’s makeup, it must not look like any one of them. You must5 see those breeds only as threads in the fabric. The making of the Doberman Pinscher is not over, but we hope you have enjoyed the story of the first one hundred years.

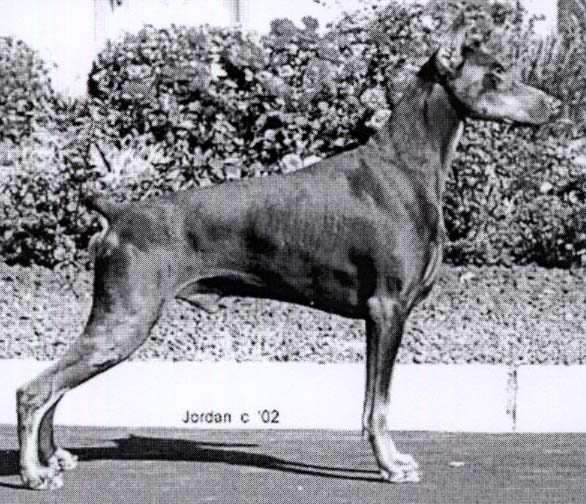

Am Ch Darwin’s Dance Of The Hour, Owners: Marilyn Altheide, Darlene Young

General Appearance | Head | Neck, Topline and Body and Tail | Forequarters | Hindquarters | Forequarters and Hindquarters together | Gait | Temperament

1899–“A”

There is no verbiage about gait in this standard.

1901–“B”

Again, no verbiage.

Circa 1901–“C”

Again no verbiage.

1920

Gait: Running gear must be light and free. Note: this appears in the General Appearance section.

1925

Again, no verbiage about gait.

1935

Gait: Free, balanced, vigorous and true. Back firm, indicating the lasting qualities of a working dog.

Faults: Lack of drive, stiffness, looseness, excessive back motion. Paddling. Throwing front or hind legs.

Scale of Points:

Gait………………………………….6

1942

Gait: His gait should be free, balanced and vigorous. When moving swiftly, he should throw his hindlegs at least as far as his front legs.

Faults: lack of drive, stiffness, looseness, excessive back motion, throwing front or rear legs, or both, in or out. Not covering enough ground with rear legs.

1948

Gait: The gait should be free, balanced and vigorous with good reach in the forequarters and good driving power in the hindquarters. When trotting, there should be a strong rear drive, with rotary motion of hindquarters. Each rear leg should move in line with the foreleg on the same side. Rear and front legs should be thrown neither in or out. Back should remain strong, firm and level.

SCALE OF POINTS

Gait…………………………………………………6

Faults: The foregoing description is that of the ideal Doberman Pinscher. Any deviation from the above described dog must be penalized to the extent of the deviation.

1969

Gait: Free, balanced and vigorous, with good reach in the forequarters and good driving power in the hindquarters. When trotting there is a strong

rear-action drive. Each rear leg moves in line with the foreleg on the same side. Rear or front legs should be thrown neither in or out. Back remains strong and firm. When moving at a fast trot, a properly built dog will single track.

Faults: The foregoing description is that of the ideal Doberman Pinscher. any deviation from the above described dog must be penalized to the extent of the deviation. & nbsp; ; &nbs p; &nb sp;

DISQUALIFICATIONS Overshot more than 3/16 of an inch, undershot more than 1/8 of an inch. Four or more missing teeth.

Note: The verbiage of rotary motion that was in the 1948 standard was removed in this 1969 standard. I was interested in the reason why, so I looked it up in the DPCA minutes in an old magazine and found this:

In the November-December 1966 issue of Doberman News in a

report of the committee on the standard October 1965 to September 30, 1966.

This report was prepared by Eleanor Houston Carpenter, chairman and read by Dr. Shute. “Under 7I, Gait, the phrase “rotary motion of the hindquarters” is an incorrect description of the ideal gait as may be seen by reducing motion pictures of a moving Doberman to a slow speed. Hence this phrase should be eliminated.”

Here is a little more on the Gait section. “Under 7J the committee is not

all in agreement on the advisability of introducing into the standard the

observation that at a fast trot a properly built Doberman will

single–track. Granted that this is correct the question remains whether the

show ring gait is fast enough to show this trait and whether any but most

practiced judge would distinguish between the tendency to “come in on line” and the fault moving too close behind. Before marking the ballot please be sure that you are thoroughly informed on this question of gait.” Interesting heh? This is a very interesting report if any of you have this magazine.

I will try to find more discussion if there was any printed. I would like to

find out who else was on this committee. I cannot find it as of now and I

will have to stop for a bit. I am missing a November 1964 issue of Doberman News which could have the minutes of the General meeting in it. The December 1964 has the minutes of the Executive meeting in it but no mention of the other members of the Standard Committee, just the above report written by the Chair-person.

1982/1990

Note: Adopted by the DPCA and approved by the AKC on February 6, 1982. Reformatted November 6, 1990. The only change in 1982 to the standard approved in 1969 was the addition of a disqualifying fault for dogs “Not of an allowed color.” The standard was reformatted only and no descriptions were changed in 1990.

Gait: Free, balanced and vigorous, with good reach in the forequarters and good driving power in the hindquarters. When trotting, there is a strong rear-action drive. Each rear leg moves in line with the foreleg on the same side. Rear and front legs should be thrown neither in or out. Back remains strong and firm. when moving at a fast trot, a properly built dog will single track.

FAULTS The foregoing description is that of the ideal Doberman Pinscher. Any deviation from the above descri

bed dog must be penalized to the extent of the deviation.

DISQUALIFICATIONS Overshot more than 3/16 of an inch, undershot more than 1/8 of an inch. Four or more missing teeth. Dogs not of an allowed color.

General Appearance | Head | Neck, Topline and Body and Tail | Forequarters | Hindquarters | Forequarters and Hindquarters together | Gait | Temperament

Forequarters: It only talks about the chest which is well rounded, not flat sided and reaching to the elbow.

Hindquarters: Powerful and muscular.

Legs: Straight. Elbows stand perpendicular under the rump and should turn out. (note the terminology in those days).

Feet: Toes well arched and closed.

1901–“B”

Forequarters: It talks about the legs. Legs: Straight, with toes well arched and closed. Elbows stand perpendicular under rump and must not turn out. Hindquarters powerful and muscular.

1901–“B”

Legs: (it is all under legs verbiage) Straight, with toes well arched and closed. Elbows stand perpendicular under rump and must not turn out. Hindquarters powerful and muscular.

Circa 1901–“C”

Forelegs: Elbow possibly are right angle with shoulder blade. Should not turn to inside or outside and should be straight to foot joint.

Feet: Round, turned neither outside or inside. Toes should be arched and closed. Nails strong and well arched.

Hindlegs: Muscular, not bowed to inside or outside.

Feet: Round, turned neither outside or inside. Toes should be arched and closed. Nails strong and well arched.

1920

Forequarters: Legs straight to the pasterns. Upper arms forming as nearly as may be a right angle with the shoulder-blades. Shoulder powerful with well-defined muscles, lying close up to the body.

Faults: Stiff or loose shoulders. Feet turning in or out. Weakness in pasterns.

Valuation By Points: Build (neck, breast, back, fore and hind quarters, paws, tail, ect…….40.

Hindquarters:

Broad and with a good angle in the upper section. Powerfully defined muscles. Neither let down nor too straight on hocks, viewed from behind, placed straight, turning neither in or out.

Faults: slender and lightly muscled hindlegs. Stiffness or stiltiness in hindquarters.

Paws: Short, well arched and compact. Dewclaws are to be removed when tail is clipped.

Faults: Paws long, flat or not compact.

Valuation by points

Build: (neck, breast, back, fore and hind quarters, paws, tail and ect.-40

1925

Forequarters: Legs seen from front and side perfectly straight, with clear round bones, muscled and sinewy. Shoulder long, well angulated, lying close to the body and being muscular.

Faults: Listed at the end of the standard. Faults are all deviations from the above standard. Especially faulty are: deviations from the correct type and in particular borzoi and greyhound type dogs, a shy, cowardly and nervous character, too light, too heavy, too low standing or distinct high legged and too narrow body build.

Hindquarters: Broad shank with long and powerfully developed muscles and well defined knee. Hocks strongly developed forming not too much of a blunt angle, however not exaggerating in angulation. Viewed from the rear the dog should not look as being built small and slim. The legs stand vertical to the grown, the hocks turning neither in or out.

Paws: Short, arched and compact. Dewclaws are not permissible, therefore should be removed right after birth if existing.

1935

Fore Quarters: Shoulders well muscled, lying close to the body. Upper arms forming as nearly as may be, a right angle with the shoulder blades. Legs straight to the pasterns. Pasterns firm. Paws compact.

Faults: Loose or stiff shoulders. French of “fiddle front”. Feet turning in or out. Front narrow. Weakness of pasterns. Steepness of shoulder, (too short upper-arm or shoulder-blade). Insufficient forechest. Paws long, flat or splayed. Note: Faults printed in italics are MAJOR FAULTS indicating degeneration of the breed.

Scale Of Points: Forequarters

Shoulders, upper arms, legs and pasterns….5

Angulation………………………………………….4

Paws………………………………………………..2 total 11

Note: It is recommended that the Scale of points be confined in use in Match Shows and Judging Classes.

Hind Quarters: Broad, with upper thigh forming as nearly as may be a right angle with hip bone. Well muscled, with clearly defined stifle. Lower thigh of good length. Legs when viewed from behind, straight, turning neither in or out. Paws compact.

Faults: Fine or lightly muscled hind legs. Steepness due to insufficient angulation. Excessive angulation. Cowhocks. Sloping or excessively rounded croup. Low tail placement. Failure to balance with forequarters. Feet turning in or out. Flat feet.

Scale Of Points.

Hindquarters.

Upper thigh stifle and hocks……………………….5

Angulation………………………………………………4

Paws…………………………………………………….2 total 11

1942

Forequarters: Shoulder blade and upper arm should meet at an angle of at least ninety degrees and not more than one hundred and ten degrees. Proportion of shoulder and upper arm should be one to one.

Legs seen from the front and side perfectly straight and parallel from elbow to pasterns, with round bones, muscled and sinewy. In a normal position the elbow should touch the brisket.

Pasterns firm, with a almost perpendicular position to the ground.

Paws well arched, compact and cat like.

Faults: shoulders too loose, too steep, (too short), overloaded with muscles. Weak pasterns, paws turning in or out. Bones too heavy or too light. French front, bowlegged front, front too narrow or too wide. Paws too long, flat or spayed (rabbit feet). Too much gap between elbow and brisket and/or forechest. Elbow turning out. Dew claws.

Scale Of Points: Forequarters

Shoulders, upper arms, legs and pasterns….5

Angulation………………………………………….4

Paws………………………………………………..2 total 11

Hindquarters: Upper shanks long, sufficiently wide and well muscled on both sides of thigh, with clearly defined knee (stifle). Hocks, while at rest, should stand perpendicular. Upper shanks, lower shanks and hocks parallel to each other, also wide enough apart to fit in with a properly built body. The hip bone should fall away about thirty degrees from the spinal column. The upper shank should be at right angles with the hip bone. Croup well filled out. Cat paws, like on front legs, turning neither in or out.

Faults: Fine or slightly muscled legs. Steepness or lack of angulation, or excessive angulation. Lack of knee development, hocks not parallel. Cow hocks, or too prominent hocks, hips too wide or too narrow. Diagonally slanting or excessively rounded croup. Toes turning in or out. Lack of balance with forequarters. Flat feet.

1948

Forequarters: Shoulder blade and upper arm should meet at an angle of ninety degrees. Relative length of shoulder and upper arm should be like one to one, excess length of upper arm being much less undesirable than length of shoulder blade. Legs , seen from the front and side perfectly straight and parallel to each other from elbow to pastern; muscled and sinewy, with round heavy bone. In a normal position, and when gaiting, the elbow should lie close to the brisket. Pasterns firm, with a almost perpendicular position to the ground. Feet well arched, compact and cat like, tuning neither in or out.

Scale Of Points: Forequarters

Shoulders, upper arms, legs and pasterns….5

Angulation………………………………………….4

Paws………………………………………………..2 total 11

Hindquarters: In balance with forequarters. Upper shanks long, wide and well muscled on both sides of the thigh, with clearly defined stifle. Hocks, while the dog is at rest: hock to heel should be perpendicular to the ground. Upper shanks, lower shanks and hocks parallel to each other, and wide enough apart to fit with a properly built body. The hipbones should fall away from the spinal column at an angle of about 30 degrees. The upper shank should be at right angles with the hip bone. Croup well filled out. Cat-feet as on front legs, turning neither in or out.

Scale Of Points-Hindquarters

Upper thigh–stifle–hocks…………………………….5

Angulation……………………………………………….4

Paws……………………………………………………..2 total……11

Faults: The foregoing description is that of the ideal Doberman Pinscher. Any deviation from the above described dog must be penalized to the extent of the deviation.

1969

Forequarters: Shoulder blade: Sloping foreword and downward at a 45 degree angle to the ground meets the upper arm at an angle of 90 degrees. Length of shoulder blade and upper arm are equal. Height from elbow to withers approximately equals the height from ground to elbow. Legs: seen from the front and side, perfectly straight and parallel to each other from elbow to pastern; muscled and sinewy, with heavy bone. In normal position, and when gaiting the elbow should lie close to the brisket. Pasterns: firm, with almost perpendicular to the ground. Feet: well arched, compact and cat like, turning neither in nor out.

FAULTS: The foregoing description is that of the ideal Doberman Pinscher. any deviation from the above described dog must be penalized to the extent of the deviation.

Hindquarters: The angulation of the hindquarters balances that of the forequarters. Hip Bone falls away from the spinal column at an angle of about 30 degrees, producing a slightly rounded, well filled out croup. Upper shanks: At right angles to the hip bones, are long,wide and well muscled on both sides of the thigh, with clearly defined stifles. Upper and lower shanks are of equal length. While the dog is at rest, hock to heel is perpendicular to the ground. Viewed from the rear, the legs are straight, parallel to each other, and wide enough apart to fit in with a properly built body. Dewclaws if any, are generally removed. Cat-feet, as on the front legs, turning neither in or out.

Faults: The foregoing description is that of the ideal Doberman Pinscher. Any deviation from the above described dog must be penalized to the extent of the deviation.

NOTE: When I began as a Doberman fancier and breeder in 1960, this standard was in place.

1982/1990

Note: Adopted by the DPCA and approved by the AKC on February 6, 1982. Reformatted November 6, 1990. The only change in 1982 to the standard approved in 1969 was the addition of a disqualifying fault for dogs “Not of an allowed color.” The standard was reformatted only and no descriptions were changed in 1990.

Forequarters: Shoulder Blade sloping forward and downward at a 45-degree angle to the ground meets the upper arm at an angle of 90 degrees. Length of shoulder blade and upper arm are equal. Height from elbow to withers approximately equals height from ground to elbow. Legs seen from front and side, perfectly straight and parallel to each other from elbow to pastern; muscled and sinewy, with heavy bone. In normal pose and when gaiting, the elbows lie close to the brisket. Pasterns firm and almost perpendicular to the ground. Dewclaws may be removed. Feet well arched, compact, and catlike, turning neither in nor out.

Hindquarters: The angulation of the hindquarters balances that of the forequarters. Hip Bone falls away from spinal column at an angle of about 30 degrees, producing a slightly rounded, well filled-out croup. Upper Shanks at right angles to the hip bones, are long, wide, and well muscled on both sides of thigh, with cl

early defined stifles. Upper and lower shanks are of equal length. While the dog is at rest, hock to heel is perpendicular to the ground. Viewed from the rear, the legs are straight, parallel to each other, and wide enough apart to fit in with a properly built body. Dewclaws, if any, are generally removed. Cat feet as on front legs, turning neither in nor out.

FAULTS The foregoing description is that of the ideal Doberman Pinscher. Any deviation from the above described dog must be penalized to the extent of the deviation.

DISQUALIFICATIONS Overshot more than 3/16 of an inch, undershot more than 1/8 of an inch. Four or more missing teeth. Dogs not of an allowed color.

——————————————————————————————————–

I don’t think that the standard was changed throughout the years to change the basic dog. I think that it was revised to better explain the ideal Doberman Pinscher in words.