Breeder/Exhibitor Ed, Conformation

“The DOBERMAN PINSCHER is a square, compact, medium size dog of

balanced proportions, noble in it’s carriage, courageous by nature, keenly

intelligent and SOUND of mind, body and joints.

If you should be so fortunate as to find two Dobermans possessing these

ten traits then, by all means, break the tie with any of your personal

preferences” . . . Bill Garnett

Sound of body vs. sound of joints. First let me discuss what being sound of joints means. For example. let’s take the point where the upper arm fits into the shoulder blade … would you not agree that forms a joint? Would you not also agree that where the upper arm meets the lower leg a joint of union is made? Would it not follow that where the lower leg joins with the pastern another joint is formed?

Having agreed to those premises one could safely say that scenario is repeated numerous times though out the entire structural make up of the Doberman. The soundness of those joint connections contributes a great deal to whether a dog flips, pops, flops, single tracks, reaches or drives when moving. One of the contributing factors to how well these joints union is how well the ball and socket or the two bones of each factor fit together.

Sound fitting ball and socket joints have a great deal of influence on the sound make up of the Doberman’s structure. Now, if we agree to that premise it would be safe to say that all joint unions are vital in the make up of a Doberman’s sound structure.

Let me give you an example just how delicately and how beautifully nature has dictated these joint unions and the results of them being sound:

“The front assembly is founded on the shoulder blade (scapula), of flat, triangular shape with a spine or ridge down the outer surface to provide muscle attachment. An oval cavity in the lower end receives the ball-like head of the upper arm at the point of the shoulder joint.

The upper arm (humerus) is a slender bone with a slight spiral twist, extending from the shoulder joint downward and backward in various degrees and lengths depending on the breed. In all, the general shape remains the same and the union of the shoulder joint is such that the opening of the angle between them is limited by a knob-like protrusion on the head of the upper arm. This has a definite influence on the function of the upper arm in movement.

The forearm consist of two bones (the radius in front and the ulna behind) and enters the structure at the elbow. The lower end of the upper arm which is round and rests in a depression atop the radius bone; it’s round head has a groove in the back side into which the ulna fits and slides to provide the leverage action of the joint. The pastern joint, at the lower end of the forearm, is made up of a number of small bones (carpal). the radius rests on a large radio-carpal in front of the group.

The most important bone here is the pisiform, L-shaped, with the short arm resting atop a metacarpal and the long arm extending backward. Near the mid point of the latter rests the tip of the ulna so that the muscular action applied to the end of the pisiform manipulates both bones and puts the zip in pad action.

Below the pastern there are three metacarpal bones, long and slender, like those in the back of our hand between wrist and fingers. there is a fifth but it is not active in the support.

The Doberman’s foot is made up of three small bones to each digit, corresponding to those that make up our fingers.” (McDowell Lyon’s ‘Dog In Action’, pages 102 – 104)

There is one more compelling observation that one can make regarding sound bones that make up sound joints. “they are the framework of the dogs body and the instruments or tools with which his muscles must work in moving him about. THEY must be considered when judging the dog.” (‘Dog In Action’ page. 112)

After saying all of that, I would hope that you now concur that bone forming joints have a life of their own and the proper fit, shape and length of those bones go a long way in the make up of sound joints thus contributing to a structurally sound Doberman.

Now to those sound joints and bones we add a “sound body” that is properly conditioned, strong muscles, tendons, ligaments, hard coat, depth, tuck and balance and to that we add a sound mind, a square and compact body, a dog of medium size that is noble, courageous and keenly intelligent and presto, with have a sound and standard conforming Doberman Pinscher.

Breeder/Exhibitor Ed, Breeding/Genetics

- Reprinted with permission

- Written and submitted by Ms Dany Canino

SOME ANSWERS TO THAT IMPORTANT QUESTION

WHAT IS NEUTERING? This is a surgical procedure to sterilize a male dog, oftentimes called castration. Both testicles are removed so that the dog is incapable of reproducing.

WHEN SHOULD IT BE DONE? Usually after both testicles have completely descended into the scrotum or anytime after 5 months of age.

WHAT ABOUT DOING A VASECTOMY INSTEAD? This procedure does render a male sterile, but because the male hormone (testosterone) is carried through the testicles, a vasectomy will not eliminate the male from having sexual desires or sexual tendencies such as; marking territory, roaming instinct, and sexual aggression against other male dogs.

SHOULD I USE MY MALE AT STUD JUST ONCE BEFORE I NEUTER HIM? This one is

multi-faceted in answer. Making the decision to allow your male to sire a litter of puppies is a lifetime responsibility. Your position as the stud owner should not end after your male has serviced the female. Those puppies that will be born as a result of your male´s sperm have to be placed into good lifetime homes. Another factor to consider is that every breed of dog is affected with different genetic problems. You would have to be a professional breeder to know what these defects were and, therefore, could be very selective as to which female the male is bred to. Otherwise you might very well be passing these same defects onto some innocent puppies and unsuspecting puppy buyers.

If you purchased your male from a pet store it probably originally came from a puppy mill, NOT A PROFESSIONAL BREEDER. This means that it´s almost impossible to check out his genetic background as so many of these people breed mother to son, sister to brother, etc, etc. These people do not “fess up” to this breeding practice and they are not above falsifying the pedigrees. That´s why the American Kennel Club has had to close down so many of these places. If your pup came from a pet shop you´ll have no concrete way of knowing what genetic faults you will be passing on if you breed your male.

WILL MY MALE BE LESS MASCULINE IF I NEUTER HIM? Your male doesn´t derive his courage from his testicles. It´s a known fact that many guard dogs and Police Dogs are neutered. This way there is more assurance that the dog will pay attention to business instead of some cute female that might wander near him. It´s quite understandable that the thought of neutering a male dog mostly affects men. They can´t help but empathize with the procedure. Male dogs that are neutered DO NOT become effeminate. These dogs will still be capable of protecting you and your property. Neutering simply means that the dog will loose his sexual desire and cannot reproduce.

HOW SOON AFTER NEUTERING CAN I EXERCISE MY DOG? You can usually take your dog for a walk the day after neutering him. If your dog is in obedience training he can resume this work a couple of days after neutering. By the end of the week everything will be back to normal.

WILL MY DOG LOOK REALLY DIFFERENT & WILL HE GET FAT? Right after your dog is neutered he won´t really look any different. He will almost look as if he still has his testicles. In time the scrotum skin will tighten up, but by then you won´t even be aware of it. As far as your dog getting fat, if you feed him properly (not too high in protein or fat) and give him exercise, there is no reason for him to get fat. A lack of hormones in your dog´s body doesn´t cause obesity in a dog. Owners are responsible for dogs getting fat.

WILL MY MALE RESENT BEING NEUTERED? Once he is neutered, especially if he is done young, he won´t even miss not having testicles. As far as resenting not being bred, if he´s never bred he won´t have any feelings about this at all. It has never been proven that male dogs experience the same sexual gratification as a human male through the sexual act.

WILL MY MALE LIVE LONGER IF I NEUTER HIM? You will certainly increase his chances of a longer life when it comes to the different forms of male cancer.

WHAT ARE SOME VALID REASONS FOR NEUTERING? One of the main reasons is the health of the animal. By neutering a male before he reaches adulthood or before his male hormones become active, you´re reducing the animal´s chances of testicular cancer, anal gland cancer, or prostate cancer. Many male animals that are left un-altered become “sexually aggressive”, not only towards other male dogs, but sometimes they even become “testy” towards people.

Every year millions of puppies and older dogs are put to sleep in animal shelters. So many of these animals are the product of people that wanted their male dog to experience the sexual act “just once”, or, they wanted to try and get a dog just like their male, or they thought their dog was so good looking that he should be shared.

NONE OF THESE REASONS ARE VALID ENOUGH TO BREED YOUR MALE.

All things considered, you´re probably better off leaving the breeding of animals to the experienced professionals.

I hope this question and answer sheet will help you to make a conscious decision. Feel free to discuss this important decision with your Veterinarian, because next to you, he´s your dog´s best friend. If you are still undecided have your male evaluated by a professional breeder of your breed to see if he or his pedigree are worthy of being reproduced.

Breeder/Exhibitor Ed, Conformation

submitted by Judy Bohnert

INGREDIENTS:

- 10 pounds of cheap hamburger meat

- 1 large box of Total cereal

- 1 large box of oatmeal (uncooked)

- 1 jar of wheat germ

- 10 eggs

- 1-1/4 c. vegetable oil

- 1-1/4 c. molasses

- 10 small packages of unflavored gelatin

- pinch of salt

DIRECTIONS:

- Mix all ingredients together well, much like a meatloaf

- Put into separate freezer bags and freeze, thawing out as needed.

- Make little meatballs and place them on top of the food

It puts weight on in a very short time not to mention adding gloss the coat. Use it every day when showing — does not produce diarrhea. It can be fed alone or, to save money, with their regular food. If you are unable to obtain all the ingredients (i.e.-the molasses and the unflavoured gelatin), it will still work wonders on your dog.

Breeder/Exhibitor Ed, Conformation

by Michelle Santana

Foxfire Dobermans

Depending on where I lived, I have road worked in a myriad of places. Here are some of them;

- Office Building parking lots (after/before hours & sometimes the more deserted ‘working’ ones.

- Side streets that have a dead end. (even in residential neighborhoods, the least crowded streets.)

- Fairground parking lots, church parking lots. virtually any road that is least traveled (and yes I’ve come across my share of cars and I pull over to make way, then continue on).

About comments while road working:

It would seem that almost everyone has to stick their noses in everybody else business. That is a fact of life, so grow a thick skin and close your ears. You don’t owe anybody an explanation as to what you are doing as long as you aren’t breaking the law or abusing your dog. IF people are pleasant and just curious, not bashing you for your method of exercising your dog, I would certainly explain the process of road working to those passers by.

In order to deal with a dog who puts up a fight about road working, I always try to start a beginner dog with an experienced dog. They learn by the example of the dog next to them. If you have no other dog available try to find someone that already does road work and tag along with them for the ‘beginning’ outings.

When I am doing one dog by themselves for the first time and they seem particularly resistant, I just reassure them everything is okay, give them the command ‘trot’ and go very slow, for short distances (1/4 mile) encouraging them the whole way. We repeat this for a week. They usually get over the ‘fear factor’ after the first week. As with ANY new experience, be patient and persistent. It is common for them to resist this form of exercise until they understand what is expected of them and the what the routine is … AFTERWARDS THEY LOVE IT, I can guarantee it!

If you sit in the back of the car while someone else drives, assuming there isn’t a ‘rim’, you can put your legs up in a “V” and have the dog run between your legs (this also helps to break side winding) it will be impossible for him to jump in the car because YOU are there. This position also allows for maximum praise/guidance from you. As the dog catches on you, you won’t have to keep your leg’s up anymore.

I recommend not starting road working until a dog is at least 18 months old. Sometimes, if done correctly, it can be done a little earlier to teach a dog ‘poise’ and carriage and correct moving habits (the distance would be Short and Slow).

If the dog is a puppy I recommend free running exercise on grass/dirt or swimming.

QUESTIONS RE ROAD WORKING WITH A CAR

Question:

In my area, weather and my current work situation prohibits outside road work. The dogs play in a 70′ x 50′ enclosure. I have a people tread mill (I couldn’t justify buying a doggie one @ $2000 plus) that is long enough for them to trot (not full extension). Is this adequate for inside road work? I have heard different views. If you set the treadmill uphill you achieve what? If at a level setting you achieve what? Which type of work affects what muscles? What is a good speed, duration, and frequency?

Answer:

Personally I find some dogs don’t do well with tread mill exercise. It makes them move funny in the rear. If I noticed this with one of my dogs I discontinued the use of the treadmill and switched to the car. Actually I never use my treadmill anymore because I can road work more dogs at a time with the car so it’s more time.

The funny movement that can occur doesn’t happen to all Dobermans. All breed handlers especially like treadmills because their coated breeds don’t damage any hair and it’s easier for their small breeds.

So, try it out with your Doberman. The bottom line is, one way or another, a Doberman has to be conditioned to be competitive. Nothing helps a Doberman look more ‘Muscular and Powerful for Great Endurance and Speed’ as per our Breed Standard, than to have a well-built, rippling, smooth-muscled body! If your human treadmill is what you’ve got then you have to make do with it! You can always discontinue using it if you find it is affecting your Doberman’s trot in a detrimental way.

Where I road work the road naturally inclines. I believe this enhances the development of the rear muscles, both inner and outer. I think road working flat really helps enhance the back muscles but I don’t think it’s necessary to have one over the other.

I also used to throw a stick up a hill for one of my dogs. It really helped develop his chest area. I don’t know that the incline derived from a treadmill would do this though because it isn’t as steep as a hill and the dogs are trotting versus really digging in at a gallop.

The frequency, duration and speed that you roadwork really depends on each dog. Some dogs have a natural faster trot and most dogs, after being road worked awhile, will trot faster naturally. So, as a result, you may find that you are continually adjusting the speed. Just make sure the speed is a nice, fluid, even, balanced motion. Something similar (maybe a little faster) than what is expected in the ring.

Duration has to start out slow if your dog isn’t used to road working. I’d go 1/4 to 1/2 mile for the first two weeks, eventually working up to two miles and sometimes more if your dog has a particularly ‘mushy’ muscle fibre or a weak top line and if this is usually it’s only form of ‘exerting’ exercise). Ideally, I think most dogs, by and large, need both road work and free running for conditioning. Even if the road working isn’t for conditioning, it’s an invaluable tool to teach a dog proper carriage and a free-flow, fluid, balanced trot such as that needed for an impressive ‘show gait’.

I have some dogs that road work every day. I have others that road work every other day. For now I would suggest every other day for you. The in-between days should be spent with extra emphasis on free running. A tennis racket and ball are great to entice all out galloping in a enclosed area. You will start seeing changes almost immediately but don’t expect anything dramatic for at least six weeks. Then you can reassess what changes should be made, hopefully with a mentor looking on (more/less road work/free running).

Question:

Do you think an inexperienced person can road work a Doberman with a car and alone or do I need to find someone to help me? I don’t want to run.

I also heard that having the dog run up and down stairs is good exercise to tighten the muscles in the back and the top line. Care to comment on that? Can you compare the two methods of exercising?

Answer:

Well yes, I think am inexperienced person can roadwork a dog! I was inexperienced once and haven’t run over any! Now I do THREE at a time! (LOL)

It’s pretty hard to ‘run over’ a dog while road working if you road work properly. I once heard of a man that did run over his dog because he had his dog on a flexi lead while trying to do it! If you roll down the window of your car, depending on its make, most tires are in front of the door area. This door area is ‘exactly’ where your dog should stay. It should have just enough lead (tightish) to stay next to your car and trot. If the dog stays in this position it is really pretty difficult for it to fall and then slip sideways under the rear tire. Physically it’s hard to do!

Now, the key is your dog. Some dogs get out of the car and take to road working like they have been doing it their whole life. Others are more ‘resistant’ and will jump and look at you in the window while you are getting back into your position behind the wheel. Some lag behind until they build up stamina

, confidence, etc. This is okay. Just be patient as eventually your dog will be able to keep up with the pace and may even ‘set’ it!

I have never had a dog that did not, eventually, LOVE road working. I recently had a ‘resistant’ one but now he loves it! Some take a little more encouragement than others; some need pinch collars because they are sure they can drag your car, (LOL) but they all end up loving it. No matter how resistant some of my clients are to the fact that they are going to have to road work their dog in order to win, the client always comes back to me and says how much their dog enjoys road working, and even when they finish the owners say they continue to roadwork the dog! Yea right, say I…it’s a tedious job and I don’t believe anyone will do it unless forced to by their handler.

Finding someone to help, initially, isn’t a bad idea. That way you and your dog will be more comfortable when your helper eventually can’t go. I often show my clients how to do it while we’re at a show or, I take their dog and train it and then hand over the job. The problem I found with a helper is usually they will not be as dedicated as you. Dedication is a must in this sport! For instance, in the beginning, my mom was the helper. She drove the station wagon and I sat on the tailgate. Eventually it was harder and harder to get her to commit to a religious routine, so I decided I HAD to do it myself. I self taught myself when I was probably only 16-17. I won’t even begin go into how to do more than one! (LOL)

As to stairs, frankly, I have NO experience in this department. Perhaps others do? My gut feeling is, if there is any other form of exercise available, use it. I would be afraid that the steepness and climbing/descending action could have a long term detrimental effect on a dogs knees, elbows, joints, etc. Let’s face it, it can take a Doberman months, if not a year or more, to finish o you have to do something that you can sustain long term. I’m not saying that stairs can’t or shouldn’t be used at all, and if it’s the only method of road working that you have available to you, then what can you do? I, personally, would just try to find a more ‘natural’ form of exercise. (and no, running along a car isn’t natural, but the ‘trot’ is).

QUESTIONS RE ROAD WORKING WITH A BIKE

Question:

Has anyone tried the ‘Springer’ on their bike? This is a gizmo that attaches under the seat and prevents the rider from becoming unbalanced and falling over should the dog decide to pull in another direction (like after a cat)

Answer:

IF a client wants to ride a bike for two miles I don’t have a problem with it. I do try to insist they use a Springer. That is pretty much the only ‘safe’ way to ride a bike with a dog in my humble opinion. The reason I prefer clients to use a car is ‘commitment’. Most of my clients work all day, come home tired and really aren’t going to commit to getting on a bike every day or every other day to peddle two miles!!

They might on the weekends but every other day for eight or more months (or in the case of a special, for years)? Not too likely. If they use the car there is no excuse, no I’m too tired or its raining or its too dark, etc. With the car they can pop in their favorite tape, relax, look out the window at their doggie enjoying the heck out of itself and toodle around for two miles (20 minutes give or take). It’s a much easier commitment for them to make. They come home with a mission accomplished feeling. The handler is happy, the dog is happy and none of it was a “Pain In The Butt” (if you know what I mean).

The reason I REALLY want them to use a ‘Springer’ is two fold:

A.) Theirs and their dog’s safety. It is next to impossible to pull a human over going after a cat or another dog with the dog attached securely (you might have to use a pinch collar) to the Springer.

B.) When a client holds the leash they tend to exert different pressure on the collar and tug on the leash as they try to keep the speed constant for the duration of the two miles. This leash/collar action can be detrimental to the dog learning to stay focused and maintain a fluid/balanced trot. It may encourage the dog to keep looking at the bike rider to see what’s up or why they are pulling/adjusting him this way and that. The whole idea behind road work, besides conditioning (at least to me), is to teach the dog to be relaxed on the lead/collar and look ahead and learn to ‘float’ in a fluid/balanced motion. That is pretty hard to do if a dog has to worry about what the bike rider is doing or if the bike rider is going to fall on them, which can really mess up a dog. I know plenty of people that fell over when on the bike and not using a Springer. So that’s my reasons behind preferring a car…but, different strokes for different folks as long as the homework gets done.

It has been pointed out to me that some bikes cannot accommodate the way the Springer attaches to them so you might want to check into this before you make the purchase of a Springer as they cost about $50.00.

Breeder/Exhibitor Ed, Conformation

by Judy Doniere,

Toledobes, USA

As a judge I am writing about dogs not standing for exams. I find that many people have never taken their pups out to training classes or haven’t been to class for several weeks. One or two classes simply won’t do a good enough job, not only for the pups, BUT MOSTLY FOR THE EXHIBITORS.

Many young dogs are motivated by their owner’s nervousness and it follows right down the lead. Many exhibitors too are rushing to set the dog up and are moving the legs all over the place, having absolutely no idea how the dog should be stacked in the first place. Sometimes when a judge is shown a dog’s mouth the poor animal’s head is down almost to the floor or possibly the handler opens the dog’s mouth so wide that they almost unhinge the jaws whereupon the pup naturally backs up.

Another problem I have seen is when the judge tries to go over the dog the handler will allow the lead to drop back on the dog’s neck so the dog is literally walking around in a circle or whatever.

The exhibitor sometimes grabs the tail and holds on for dear life using that as a prop to hold the dog in place.

Another problem that I have seen is that the handler will allow the dog to lean against them and thus enabling the dog to use the handler as a security blanket.

I have found that instructing the exhibitor to stand to the front of the dog and hold the head straight while I go over the body works like a charm in 90% of the cases.

Please exhibitors … go to handling classes for several weeks with your dogs whether you are experienced in showing or not. The dog and you need to get it together. Why do you think Handlers suggest you send your dog to them for training? They know how to present a dog but need to work YOUR dog. Every dog is handled differently.

Is it any wonder dogs or pups don’t stand for exam? The dog has to know what is expected from the handler and vice versa.

Breeder/Exhibitor Ed, Conformation

Tracy MacLean, Shayera Dobermans

From making out an entry or using an entry service to what to take to the show with you.

This is how I enter and approach dog shows:

How far do you wish to travel may play a part. In Canada we don’t use entry services, therefore you would have to get a premium list form the club or show secretary. You can get the information through the Dogs in Canada magazine. A lot of clubs have Websites as well. Premium lists are available from the dog show secretary’s tables.

Honestly evaluate your dog and ask yourself is he ready to win or are you using the show as socialization and training? If he is ready to win pick your judges as to who you believe does a good job, knows the Doberman Pinscher standard and is not afraid to use it!

Decide which class your dog would do best in. In Canada the most commonly entered classes are Junior puppy (6-9months), Senior puppy (9-12month) and Open (any age). In breed specialties you will see some use of the other classes such as Canadian bred and Bred by Exhibitor. These classes are also offered at the All breed shows but are usually not used. The Specials Only class is for Champions only.

Fill out the entry making sure all information is correct — double check it. Write the check for the correct amount and mail in your entry in plenty of time to make it to the show secretary before the show closes. Nearly all shows held today have a Fax entry service which usually has an extra charge added for Fax service but you know your entry will have made it. Again make sure all information on the entry is correct and add your credit card number to the entry.

Next:

written and submitted by Tracy MacLean, Shayera, Canada

Breeder/Exhibitor Ed, Conformation

written and submitted by Pat Hastings

I personally feel that there is VERY LITTLE POLITICS involved in the sport of dogs. As I say in my seminar, one of the most important things you have to learn is that it is not the DOG that is judged at a show. It is the PACKAGE. That package need to include a good dog but it must be properly raised, fed, taught, trained, groomed, conditioned and presented. The judge has 2.4 minutes to judge your dog. That includes his paperwork, winners classes and taking pictures. That does not leave much time to judge the dog. Most judges do not have the ability to see, in that tiny amount of time, other than what the handler presents. Keeping that in mind, it is very simple to understand why the best dog does not necessarily win. The judge plainly does not have time to see past a poorly groomed, conditioned, trained, presented dog to see what might be there if things were different.

Becoming a judge does not change who you were before you were a judge. If you were a crooked handler you will probably be a crooked judge. If you were a stupid breeder you will probably be a stupid judge. If you did not have a clue as a breeder or exhibitor you won’t have a clue as a judge.

That is not POLITICS; that is human nature.

If everything a judge learns about a breed comes from just one area or one breeder then that judge is probably going to judge that breed differently than another judge who has watched the breed all across the country and has been mentored by breeders from entirely different lines. That again is human nature not POLITICS.

Every human uses one side or the other of their brain in a stronger fashion. If you happen to use your artistic side more then you are much more likely to judge more on type. If you use the other side which is more logical and systematical then you are probably going to look more at structure. Who

you are and how your mind works determines to a large extend how you judge. But here again that does not make it POLITICS.

Then factor into it the simple fact that the majority of people on this earth are followers. Not just in our sport but in the world at large. If you are born a follower then you do not like to make waves. If everyone else is doing something then I guess that is what I should be doing also. That is why advertising works. Here again this is not POLITICS; it is human nature.

In the classes there may be a lack of knowledge but very seldom will you see any politicking going on. When it comes to the Groups and BIS there may be a little of it involved but I think the fancy at large would be shocked at how little politics there are, even at that level.

Personally, I feel the least political show in the country is Westminster at the Garden. I feel that every judge there is doing his absolute best to put up the best dog of that breed on that day. No one ever said you had to agree but if the choice is different that yours might have been it does not make it POLITICS.

Breeder/Exhibitor Ed, Conformation

written and submitted by Bill Garnett

“the DOBERMAN PINSCHER is a square, compact, medium size dog of balanced proportions, noble in its carriage, courageous by nature and SOUND of mind, body and joints”

How many times have you heard owner-handlers explain why they didn’t win by using some of the following excuses; “The handler who won and the judge are old drinking buddies”, “The judge is just a crook”, “The judge only puts up big, red, ugly dogs”, “The judge is incompetent and knows absolutely nothing about the Standard and even less about movement”. The excuses go on and on and on. To say that none of them is relevant would not be rational, but, they can only be as relevant as you, an owner-handler, will allow.

Let me tell you something that’s going to startle you. As an owner-handler you have the advantage over the professional handler. Why? Because you and you alone control every aspect of your dog showing involvement. From the quality and condition of the dogs you show, to the very judges you show under. If, in the foregoing scenarios, the judge was indeed a crook . . . then why were you there? If he only puts up big, red, ugly dogs . . . then why did you show him a smooth, standard, black dog? If he is indeed incompetent why did you expect more? If he knows nothing about the Standard and even less about movement why do you expect him to recognize it in your dog? My point is this. If any of the accusations were true, you should have been elsewhere. I personally always felt it was better to drive eight hours and have a chance to win than to drive one for a guaranteed loss. At the risk of being cruel and blatantly blunt, 75% of owner-handlers lose because their dogs in the majority of cases are inferior to the professional handlers’ for whatever reasons. They are not conditioned as well, groomed as well, trained as well nor presented as well.

At this point I know what you’re thinking, “I thought you said owner-handlers have the advantage.” And again I say they do, but only 25% use or take advantage of that advantage. Let’s talk about that 25%. This group has learned how to win by controlling ever aspect of their dog showing involvement, through sacrifice, hard work, early hours, late hours, judge research, education, dedication and planning that makes the CIA look like a Boy Scout troop. Lets take a look at the things that a successful owner/handler does to get and maintain that advantage.

The first step in establishing their advantage is in the selection of the dog they plan to show. Seventy-five percent of owner-handlers, for a whole host of reasons, err at this juncture,. From kennel blindness to breed ignorance to just plain being sold a poor specimen from a so called breeder. For whatever the reason, it happens and right off the bat you’re at a disadvantage. Believe me, the advantage starts with your selection of the dog you plan to show. I don’t believe anyone would argue that point. Make no mistake about it! It must be superior to the professional handler’s dog. If you think for one minute you’re going to beat the handler with a mediocre dog or one just as good as his forget it! He has years of experience convincing judges that his mediocre dog is better than your mediocre dog. Trust me he’ll beat you every time, he’ll clean your plate! You have to have the better dog! You must select a better dog from the start! And don’t think the handlers don’t know who has the better dog. Let me tell you a story about that. I was showing a future BIS bitch in the black open bitch class when the professional handler in front of me turned around and complained that she wished they would stop lining up the class numerically. I asked, “why” she said, ” that gorgeous bitch of yours shows up every fault in my bitch. There’s just no way my bitch can beat her being so close to her”. Interesting that the pro felt if she could get away from my bitch she may be able to sell the judge that her bitch was better. What does that tell you about some judges? The pros know. But believe me you’ve got to have the better dog. How to select a better dog would encompass another entire article. However, there are some things that have served me well and I’m more than happy to share them with you.

Never! I repeat, never be in a hurry when choosing a puppy. If he’s good today he’ll be even better tomorrow. Beware of picks of litters. Picks of what litter? The pick of one litter may be the least of another. Grading litters is easy, but are there any standard conforming prospects in them? Remember every litter has a best puppy, but best of what? Try to view the litter over a period of time. I personally like to view puppies at 8, 10 and 12 weeks. But the best possible advice I can give you is. “If something bothers you let it”! By that I mean don’t let a fault be explained away by a self-serving breeder with the normal rhetoric, “He’ll outgrow that” or “he was sick last week,” or “a little exercise will strengthen that” and last but not least, “he looked great last week”. Believe me, if it bothers you let it! If it bothers you now, it will bother you twice as much later. If it bothers you now think how it’s going to bother the judge. The bottom line is you must start out with a good, standard conforming

puppy! It must be better than the handler’s – if not you’re in for an expensive and demoralizing lesson.

At this point you may say, what’s to prevent the professional handler from having a good one as well. And to that I say nothing, absolutely nothing! Remember, in 75% of the cases he will have a dog that is as good or if not better. But, he is not invincible. He has factors working against him that are at times difficult to overcome. You see his selection method doesn’t “always” provide him with the best dog. His evaluation is sometimes tainted by a variety of factors, the least of which could be a mortgage payment, a motor home note, or an overdue American Express bill. Into this picture “strays” a mediocre dog with “deep pockets.” You’d be surprised how fast that dog secures crate space in the handler’s van for an extended stay regardless of his quality, lack of condition, or his inability to win under good judges. If you’re going to be an owner-handler you have to be honest with yourself. Do I have a good dog? Is he better than the handler’s dog? If not, take him home and love him to death until the day he dies. But if you’re going to continue to be an owner-handler you’ve got to start with a damn good representative of the breed. And it can still go down hill.

So, now you’ve got a good one. Is that all it is to it? Just wait until it’s six months old and go out and beat the handler? Wrong! First, it has to be in better condition both mentally and physically and then it has to be better trained than the handler’s dog. If not, he’ll nail your hide to the wall. This is not as difficult as it may sound. You see, the handler has to condition and train a stable of dogs. Unless he has kennel help and plenty of it, he doesn’t have as much time to devote to each dog that you do. Now the advantage swings in your favor for you only have one or two dogs with plenty of time to do it right. However, the advantage swings right back to professional if you don’t get out of the bed in the mornings and off the sofa in the evenings.

Talk to ten successful owner-handlers about how to condition and train a puppy and you’ll get ten different answers. However, the first thing to remember is that he is a puppy and the three most important ingredients in training a puppy are patience, patience, patience. So how do you go about conditioning and training a puppy? I can only tell you what has worked for me.

At sunrise it’s up and out, taking the puppy for a nice walk. If the area will permit (safety factor) I

let him off lead for a short periods of time. Off lead he’ll follow you – you’re his security blanket. This exercise helps with bonding but also helps in developing his sense of confidence. He’ll tell you when he’s had enough. He’ll start lagging behind, sitting or lying down. You’ll develop a sixth sense about his endurance. Anywhere from 20 to 30 minutes and it’s back home, up on the grooming table for a nice brushing. All the while you’re talking to him, reinforcing his love and trust for you. Bait him a few times and give him a treat. After brushing. feed him and put him down for a nap. Around 10:00 to 10:30 put him out in the yard to run and play with another dog or puppy that he gets along with, or if you are available, create some games and situations to keep him romping and playing. Around 11:00 to 11:30 bring him in, brush him, praise him, bait him, feed him and put him down for a nap. Around 2:00 to 2:30 it’s up and out for a couple more hours of play including house time for socialization. At 4:00 to 4:30 it’s back on the grooming table for brushing, praising, baiting and down for a nap. At 6:00 to 6:30 it’s time for a nice walk and some off lead romping. Back home by 7:00, brush, praise, feed and down for a nap. At 8:00 to 8:30 it’s up and out and then into the den for house play and more socialization. At l0:00 to 10:30 it’s out for the last time and off to bed. You do this routine not once a week, not twice a week, not three times a week, but 7 days a week, every week. You can vary the routine with trips to shopping centers, office buildings, parks or little league ball games. You see, proper conditioning is mental as well as physical. And those side trips will get him used to different sounds, smells and looks. Always keep plenty of treats in your pockets to reward and praise him for his accomplishments whether it be tilting at buttercups or coming when called. As the puppy gets older, keep him on the lead longer. This establishes your control. Off lead the puppy may develop too much of a sense of independence, if allowed to get out of hand it can create problems when training him for the show ring. Flexi-leads are wonderful, but I personally have found them not to be controlling enough for a puppy and you may lose a split second of correction time in the beginning. Never! Never! Never correct a puppy too long after a mistake. It’s either right away or not at all. He has to know why he’s being corrected. If too much time elapses he may become confused and less sure of himself. Remember. . . long praising . . . quick and short corrections!

As the puppy develops physically and mentally and you have gained control of him on and off the lead, usually around 4 1/2 to 6 months, it’s time to teach him timing, rhythm and foot placement and continued conditioning. To accomplish this I measure off a figure eight with the two circles having 20 step diameters each. Start by gaiting the puppy, or I should say attempting to gait the puppy around the figure eight with him on the outside of the circle off of your left hip using a six-foot lead, giving and taking lead as needed, based on the variance of his pattern. As the puppy learns his paces you increase the number of laps from 5 to 10 to 15 to 20 to 25 to 30, based on his interest span, development and performance. If you have laid out the circle properly, 30 laps should equate to a mile. Coupled with the circle gaiting, I teach the puppy to fetch a rubber ball are a frisbee. The benefits of which are two-fold. Almost all puppies enjoy chasing and fetching and the short quick burst of speed breaks up the fat in the hindquarters, setting up good hindquarter and ham development. What is important to note at this point is that you only incorporate the fetching and circle gaiting exercises into his regular routine every other day. Just as in body building, the first day of exercise tears down and the second day of rest builds up. Remember only every other day!

Let me take this time to point out just how the fetching and circle gaiting procedure is integrated to derive the maximum benefit. After briskly walking your dog for about 1/4 to 1/2 mile and he’s loosened up, it’s time for the fetching. This should be a real fun time for you and your dog. Usually when the ball or frisbee comes out, he’ll get all excited and start bounding around waiting for you to throw it. This is what you want to encourage; for it instills enthusiasm, attitude and an intense happy expression. You fake throwing it sometimes to get him all worked up. Now this is important. When you begin throwing the ball or frisbee, try to develop and maintain a rhythm to keep him moving, whether its bounding up and down or chasing, only throw it about 10 to 20 yards to insure that he sprints for it. As a friend once told me Dobermans are sprinters not marathoners; we want sprinter’s muscles not long-distance runner’s muscles. Do this 10 to 12 times. Then after only a couple minutes rest, go right to the circle gaiting. As I mentioned earlier it’s 30 laps. But what I didn’t mention is that it is 15 laps clockwise and 15 laps counter-clockwise. This exercise not only continues the hindquarter and ham build up that the sprinting started, but contributes to his overall tone as well by making sure that he develops both sides of his body equally. After mastering this exercise, what you will discover is, not only will you have a puppy beautifully conditioned puppy but one that is a picture of timing, beautiful rhythm, wonderful foot placement and the two of you will be a picture of teamwork that any decent judge will recognize and appreciate. It’s really beautiful! After 30 laps you toss the ball or frisbee for 5 more sprints, only 5, then a walk of 1/4 to 1/2 mile and then home. Remember, only every other day for the ball fetch and circle gaiting routine! Also remember to carry plenty of treats and start to surprise him with when he gets one. Never give him one when his is doing his figure eight routine. You don’t won’t him looking for treats or bait while he is gaiting.

Now we have a good dog in great condition, both mentally and physically. Are we ready to do battle with the professional handler? “Not so fast my friend” . . . to quote Lou Corso: “Now we must learn to out groom the handler.” We do so by learning to sculpture the outline of the dog to the degree that not a hair is out of place. First we shave the insides of the ears. Then we create a clean line by shaving the back edge of the ear of all hair that has grown beyond the edge. Then we shave off the whiskers. I use a #10 blade. Some people prefer a #15. Shave the back of the leg and pastern of any protruding hairs that break up a clean line from elbow to ground. Then, using a pair of cuticle scissors, trim the hair from around the toenails and using your clippers, shave any hair between the toes and under the pads. Then I use a black magic marker and color the nail. All of this improves the look of the feet 200%. Looking at the underline of the dog, trim any excess hair that prevents a clean unbroken line. Pay particular attention to the skirt. Next, using trimming scissors, cut in the tail by defining where the black or red meets the tan or rust. You can actually raise the set of the tail, if needed, by the way you cut it in. Next, trim any excess hair on the back of the legs that breaks up the line flow. Do the rear feet exactly as you did the front. Now take a pumice stone and go completely over the dog, stripping him of all dead hair and any undercoat he may have. Then brush him from stem to stern, after which you use a high quality coat gloss for sheen and coat enhancing. Toe nails are trimmed and filed once a week and kept no longer than 1/4 to 3/8 of an inch. Not only does this protect the feet by preventing splaying, it improves and maintains them as well.

Now we have a better dog, in better condition, both mentally and physically, groomed to perfection. We should be ready to take

on the handler now, right? Wrong! Having a better dog, perfectly trained, in beautiful condition, groomed to perfection means nothing unless we show him under someone who knows the difference and couldn’t care less about who’s showing it. So the next thing we must do is learn now to identify those judges. Personally I have found all-rounders with a good reputation to be good candidates for an owner-handler to try. Breeder judges often are tough for a newcomer, particularly if you and your dog aren’t aligned politically. Judges with the working group, that have decent reputation have a sense of breed type and generally know balance and soundness and for the most part will go with the best dog. Pay particular attention to the judges who give owner-handlers the Reserves but never Winners, the Bests of Opposite but never the Breed, the Class but not a look in Winners. Scour through breed publications with a fine tooth comb, looking for owner-handlers winning and the judges they won under. Pay special attention to judges putting up good dogs, regardless of who is showing them. But really pay close attention to the judges putting up the bad dogs. Remember once burned, twice shy. Judges don’t change. They go on forever doing the same things, good or bad, for whatever reasons. Start developing a good guy, bad guy list, but be fair. If you’re in the hunt and the judge beats you with another good dog, he still belongs with the good guys. What you must understand is that handlers don’t pick judges all that close. For the most part they go right down the road. You must remember, the handler holds a trump card. Win or lose, he’s cashing someone’s check. You can be more selective than the handler. Based on your good guy, bad guy list you can actually increase your odds of winning considerably and in doing so enhance your advantage.

At this point the advantages are really piling up, but you’re still vulnerable. Up to now all your preparation has been leading up to the dog show. Now comes crunch time, the show weekend. You feed your dog a normal meal Friday morning after you’ve groomed him to perfection and packed your van neatly with nothing rattling. Rattles drive me crazy and I personally feel they can unnerve a dog. Why should your dog have to listen to a rattle for 400 miles? Leave home in plenty of time to stop and exercise your dog along the way. I usually stop every four hours. A dog that feels good . . . acts and looks good. I try to arrive at my motel no later than 8:00 p.m., which gives me enough time to exercise and feed my dog a light meal of one or two milk bones or a half cup of kibble. We rest until about 10:00 or 10:30, out for exercise and in bed by 11:00 or 11:30. It’s interesting how few people you

see exercising their dogs at this time. You hear them laughing and talking in their rooms or watching TV while their dogs count the hours until morning. These are usually the same people that are making the excuses the next day as to why their dogs didn’t win.

My dog and I are up early Saturday morning. He’s exercised, I’m showered and dressed, and we are out in time to get to the show grounds at least 1 to 1 ½ hours before our breed judging. You may ask, why do I do this, why such a demanding routine? And why so early? Well, believe me, it’s the difference between winning and losing as far as I’m concerned. I’ve gone through the agony of picking a good dog, the rigors of conditioning, training and grooming him, walked hundreds of miles in heat, rain and humidity, studied every publication I could get my hands on and sorted through every tidbit attempting to evaluate judges, planned my battle and picked my battlefield and then do I blow it all the day of the show for an extra hour of sleep. No way. I’m going to get my dog settled in and walked around the show grounds, exercising and introducing him to any strange circumstances between my setup area and our ring that could startle him if happened upon by chance later on in the day. Back to our set-up. I re-groom him although I groomed him before we left Friday. After grooming I put him up, making sure he has plenty of ventilation and he’s comfortable. Then it’s off in search of my first cup of coffee. But the preparation doesn’t stop there. I bump into friends and ask them what they know about my judge. Sometimes you get useful information, sometimes not. If my breed is later on in the schedule, I’ll go and watch my judge evaluate other breeds. I try a get a feel for the things they feel are important and what their emphases are and a sense of timing of their procedure. Sometimes I get such a good feeling for a judge’s procedure that I am able to anticipate every move he or she makes. It’s a wonderful feeling. Now I’m 100% prepared. No stone has been left unturned that would aid me in my preparation and help maintain my advantage as an owner-handler.

Now let’s take a look at what kind of morning our competition has been having. A couple of dogs have soiled their crates. He’s got that to clean up. A couple of other dogs won’t dump because they don’t like the confines of an ex-pen. One or two owners have been hanging around since dawn driving him crazy and wasting his valuable time. One or two dogs look kind of gaunt. They won’t eat on the road in either their crates or ex-pens. He’s worrying, “I’ll have to stuff them tonight”. Checking his schedule he sees that he has two conflicts. He’s having trouble finding someone to cover. His kennel help quit 3 weeks ago. He has a problem check from a client that he has to get straight before he’ll show that dog today. And to top it all off his generator is on the fritz. With so many dogs he’s going to have a problem keeping them comfortable. And what does he have to look forward to but an owner-handler who has a good dog, in wonderful condition, beautifully groomed, trained to perfection and feeling like a million dollars. On top of that the judge knows his stuff and the owner-handler knows everything the judge likes or dislikes. Now you tell me, which of these two people would you rather be?

It gets better for the well prepared owner-handler. What’s happening with the other 75% of the owner-handlers? Well, so far they haven’t gotten to the show grounds. In order to save a motel bill they left at 3:00 am. for what they thought was a five-hour drive. At this point they’re backed up on the interstate somewhere, their dogs need exercising badly, they’ve got another 55 miles to go with only an hour to make it. Finally they roll in five minutes before their class, whack off their dog’s nails, hit or miss his whiskers and don’t understand why he’s roaching going around the ring. They have no idea of the judge’s procedure and are too tired and disgruntled for the judge’ s instructions to sink in. Now are you ready for this? They lead the lynch mob who seeks to crucify you because your dog won. It makes no difference how nice he is, how well he’s conditioned, how perfectly he’s trained, how beautifully he’s groomed, that he looks and acts like a million dollars. They don’t applaud the judges for knowing their stuff or you for knowing your stuff. No, they resort to their old standby, “It was a fix”. I guess in a way, you did fix it, . by sacrifice, hard work, homework, teamwork, education and just plain dedication. So you see. Owner-handlers do have the advantage and any truly “professional handler” will tell you that. It’s what you do with the advantage that counts. Unfortunately, 75% of owner-handlers don’t take advantage of their advantage.

I hope in some small way this article will help the 25% of owner-handlers that do it right, to grow to 30%, 40%, 50% and even higher. A man and his dog is truly what the sport of purebred dogs is all about. The pleasures of those moments are the memories of a lifetime.

Breeder/Exhibitor Ed, Conformation

by Robert Vandiver

AKC defines “Breed type” as the sum of the qualities that distinguish dogs of one breed from another.

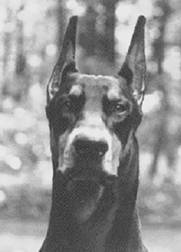

Richard Beauchamp in his book Solving the Mysteries of Breed Type states “There is no characteristic among dog breeds that is more variable than the head, and it therefore imparts individuality to each of the breeds.”

This statement makes the case that the head is one of the most Important elements that identify “breed type.” It applies equally to all breeds, including the Doberman.

Given the importance of the head to identify the Doberman as a Doberman, judges must put head conformation in proper perspective. What does that mean? It means to the Doberman fancy, that the head is important … even essential to breed type … but the Doberman is not a “head breed”.

We all know what a “head breed” is. It´s a breed that has let the head become the most defining element of breed type. Unfortunately, when a breed concentrates on heads to the exclusion of other qualities, those other qualities suffer. What results is a breed with a beautiful head, that often times have poor structure, proportions, and movement. As you observe other breeds, it will become obvious which ones are “head breeds”.

Doberman fanciers are inclined to take a middle of the road approach. They expect the head to be considered equally with other type-defining characteristics. The head is not more important than profile, gait, angulation, or proportions, but is certainly equal to each of them.

The judge simply has to decide for himself the level of importance the head has in defining the overall breed.

There are three disqualifications in the mouth of the Doberman. They will not be discussed as one of the defining elements of the Doberman breed, simply because a dog with a disqualification is disallowed from any consideration. Further evaluation of the head or any other attribute is moot. A discussion of the mouth appears later.

The first things that you should notice about the head are the overall shape and size.

The standard describes the head as “Long and dry, resembling a blunt wedge in both frontal and profile views. When seen from the front, the head widens gradually toward the base of the ears in a practically unbroken line.”

“Long” is not a quantifiable description, but for the Doberman it is generally considered to be about equal to the length of the neck, and about half the length of the topline as measured from the withers to the base of the tail. You can confirm these general guidelines by measuring the drawings in the Doberman Pinscher Club of America Illustrated Standard and by measuring photos of dogs considered as having correct heads.

Of course, “dry” simply means no loose skin, with tight lips and flews.

Figure 1 will help to visualize the look of the blunt wedge. These two graphics show the head as a blunt wedge when viewed from the front or in profile. When facing the Doberman, you should be able to place your flat hands against sides of the muzzle and cheeks and feel the smooth flat planes of the dog´s head. On a correct head, your hands will form the flat planes of the blunt wedge.

The “blunt wedge” is another non-measurable description. A blunt wedge may be fairly wide, somewhat narrow, or in between. There are no concrete measurements to give as guidelines, simply because different head shapes are correct for different body styles. A heavy boned, substantial dog will nearly always have a broader “blunt wedge” than a less substantial one. A refined dog may have a narrow “blunt wedge”. Any of these may be suitable for that dog.

Note the standard also calls for “Jaws full and powerful well filled under the eyes.” If a dog does not have sufficient muzzle and underjaw, then the head won´t form the planes of the blunt wedge. The full muzzle and underjaw are also important to hold the 42 large teeth required by the standard.

It is the judge´s responsibility to see enough Dobermans and to be mentored by enough different people to determine the normal acceptable limits of the “blunt wedge”. The judge can then evaluate within those limits, and reward dogs that fall within the acceptable norm.

The standard continues “Eyes- almond shaped, moderately deep set, with vigorous, energetic expression. Iris, of uniform color, ranging from medium to darkest brown in black dogs; in reds, blues, and fawns the color of the iris blends with that of the markings, the darkest shade being preferable in every case”

This paragraph is self-explanatory. The key words to remember are “almond shaped”, “dark”, and “expression.” The first two are easily understood.

The term “expression” is not easily described. In the Doberman we expect a look of intensity. The dog´s expression should convey the image that is described in the General Appearance section of the standard “Energetic, watchful, determined, alert, fearless”.

A good way to describe expression is the overall image formed by the head position, facial mood, lips, eyes, ear carriage, muscle intensity, and so forth. Doberman fanciers often call the typical expression the “look of eagles”.

Describing correct expression is a lot like defining quality. It has been said of quality “I don´t know how to describe it, but I know it when I see it.” Your mentors will help you understand correct expression by showing you examples. With enough study, you´ll know it when you see it.

In describing the ears the standard says “Ears- normally cropped and carried erect. The upper attachment of the ear, when held erect, is on a level with the top of the skull.”

The standard is clear on the placement of the ear, i.e. level with the top of the skull.

The discussion of ear cropping however is not quite as clear. The statement that the ear is “normally cropped” is sometimes interpreted to mean that it is typically cropped, but not required. The phrase “and carried erect” clarifies that our breed is a cropped breed and the ears are carried erectly.

Uncropped ears are allowed, and some Dobermans have finished their championships with uncropped ears. Nonetheless, uncropped ears should be thought as a deviation from the standard. You must make your own decision as to the magnitude of the deviation. Bear in mind that you must also think about the impact that uncropped ears have on expression and the overall look of the dog.

Consider the planes of the head (Figure 3). The standa

rd states: “Top of skull flat, turning with slight stop to bridge of muzzle, with muzzle line extending parallel to top line of skull. Cheeks flat and muscular. Nose -solid black on black dogs, dark brown on red ones, dark gray on blue ones, dark tan on fawns. Lips lying close to jaws.”

The description of most characteristics of the head as set forth in this part of the standard are clear and need little amplification.

One characteristic of the head that is not in the standard is the relationship of the muzzle length to the back skull length. Though it is not addressed in the standard, the Doberman Pinscher Club of America insists that the correct Doberman head have a muzzle length that is equal to the back skull length.

This is an issue that has never been contested by members of the Doberman Pinscher Club of America. All knowledgeable members of the fancy (breeders, judges, and handlers) agree that the muzzle and back skull should be of equal length.

The impression one gets upon viewing the Doberman head should be one of angles and planes. The skull and muzzle are straight and flat. The underjaw is straight. The cheeks are flat. The ears are erect with straight edges on the front and back. There is no description in the standard that calls for a curvy, soft-looking head.

Although some breeds have standards for the head that are very similar, representatives of that breed are often found to have curves and a soft look about them. This is not typical of the Doberman, even though the written word is similar for both breeds. Remember that the Doberman head is one of angles and planes.

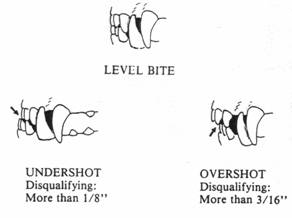

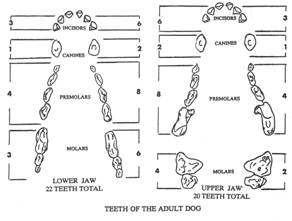

Now let´s discuss the teeth and the disqualifications. The standard says “Teeth- strongly developed and white. Lower incisors upright and touching inside of upper incisors a true scissors bite. 42 correctly placed teeth,- 22 in the lower, 20 in the upper jaw. Distemper teeth shall not be penalized. Disqualifying Faults:- Overshot more than 3/16 of an inch. Undershot more than 1/8 of an inch. Four or more missing teeth.”

The teeth are important because they are integral to just about everything a dog does. They are not there in the Doberman just to grind food to digest. They are at the core of his very existence. They are his defense mechanism, his means to acquire food, and his offensive weapons for his originally intended work. As importantly, the mouth and teeth are the dog´s arms and hands. He must use them for picking up items, transporting them, and placing them where needed. Indeed, so vital are the teeth that they play a critical role in the birthing process of cutting the umbilical cord.

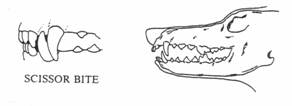

Our standard calls for 42 correctly placed teeth. Let´s first discuss the bite. The correct bite occurs with the outside top edge of the lower incisors meeting the inside inner edge of the upper incisors as shown in Figure 4. Further, the upper and lower premolars intermesh evenly.

Incorrect bites include a level bite (the upper incisors meet the lower incisors at the biting edge) an undershot bite (the lower teeth extend beyond the upper teeth) and an overshot (the upper teeth extend beyond the lower teeth without contact). All are shown in Figure 5 below:

There should be 42 teeth as shown in Figure 6. This is common to all dog breeds, but for some breeds, teeth are more important than others are. The Doberman is expected to have a full complement of teeth.

|

|

|

Figure 6 Correct teeth placement

|

The teeth and the muzzle and the underjaw are all interrelated. Each has an important affect on the other. Missing teeth are considered to be a structural fault because they have the potential to affect these other elements of the head and because of their importance to the functioning of the dog.

The Doberman judge must take examination of the mouth seriously. With each additional missing tooth the dog more closely approaches disqualification. This is not to say that a dog with a missing tooth or two should not be rewarded for his virtues. Dobermans with missing teeth do become champions. It is the judge´s responsibility to weigh the deviation along with the merits and other deviations of this dog. If a dog with a missing tooth more closely meets the standard than the competing dogs, by all means reward him. Many judges do not consider a missing tooth as a serious fault. Two missing teeth are generally considered serious, and three are very serious.

Missing teeth can appear in a number of places. Sometimes there will be five incisors that are evenly spaced, and a missing tooth can be difficult to detect. Missing premolars are the most common. Occasionally the rearmost molar is missing, especially on the lower jaw.

When examining Dobermans, you will sometimes find extra teeth, usually in the forward premolar area. Although there is no disqualification for extra teeth, the standard does call for 42 correctly placed teeth. Extra teeth deviate from this in two ways 1) the extra number of teeth is a deviation and 2) the extra teeth affect the correct placement of the other teeth.

One or two extra teeth are not uncommon. Three and four extras are seen occasionally.

When extra teeth are found, the premolars are smaller to allow space for the extras. It is easy to visualize judges forgiving extra teeth, until it becomes common to have too many small teeth … piranha-like in appearance. This is not the mouth that the standard requires.

Earlier we mentioned the importance of occlusion as it relates to the standard phrase “42 correctly placed teeth,- 22 in the lower, 20 in the upper jaw” It is important to note the intermeshing of the premolars to determine correct occlusion. Figure 7 and Figure 8 below will show you the correct and incorrect occlusion that you may encounter.

|

|

|

Figure 7 Correct Occlusion

|

|

|

|

Figure 8 Incorrect Occlusion

|

Examining the mouth is not a difficult task, once it has been practiced. The Doberman exhibitors are usually excellent trainers and presenters of their dogs. Dobermans are trained as pups to have their mouths examined, and there is seldom a problem in the ring.

You may ask the exhibitor to show the mouth, or you may examine it yourself. Both methods are commonly practiced in the Doberman ring. Most exhibitors are prepared for either option. Be careful when allowing an exhibitor to show the mouth that the exhibitor doesn´t cover gaps (missing teeth) with their fingers.

We have covered the head in detail, but it is important to summarize the essential elements. A correct Doberman head will have these six characteristics:

- Blunt wedge from the top or in profile

- Full muzzle and underjaw

- Equal length and parallel planes (top of muzzle and head)

- Dark almond eyes

- High ear set

- Doberman expression

Find these six characteristics and you have found a head that conforms to the standard.You will find dogs that meet these characteristics, but are dissimilar in appearance. That is perfectly normal and acceptable, because much of the evaluation of the head is subjective. Expression, angle of the blunt wedge, balance with the body and other aspects of the head are subject to the preferences of the judge. As long as the head has the general appearance of planes and angles and as long as it meets the six criteria listed above, then the judge is free to select the “best” head based on his own desires.

The photos that follow are considered to be examples of pleasing Doberman heads.

Acknowledgements

Artistic drawings courtesy of Jeanne Flora

Photos courtesy of Cheri McNealy

Outline graphics from the DPCA Illustrated Standard 1993

About the Author

Bob Vandiver has been involved with Dobermans since 1969. He and his wife, Nancy, have done limited but successfully breeding under the Mistel prefix. Bob was approved to judge Dobermans in 1995 and is now approved to judge all working breeds and many of the sporting breeds.

Judging the Doberman Head

©by Bob Vandiver

Breeder/Exhibitor Ed, Conformation

submitted by Marj Brooks & written by Linda C. Krukar, Dabney Dobermans

The Doberman Pinscher is a popular and ‘high profile’ breed at the shows. The quantity of dogs does not necessarily indicate the quality of the dogs. It’s important to know and understand the standard so it can be applied instead of judging to personal taste. The dog that best meets the standard may not be the dog you would want to take home with you. The dog that best meets the standard may be the one that looks different from the other dogs. Compare the dog against the standard and not against the other dogs in the ring.

Be comfortable enough with the standard to judge the dogs and not be influenced by such factors as the number of dogs a handler brings to you, the body language they may use, the faces they may make, the quality of the handling, or advertising. You can find a good dog if it’s there and usually when it’s left on it’s own — while moving or free

standing, something that any good Doberman can do by itself!

The Doberman is NOT a robot! While it is beautiful to watch a perfectly trained dog stand motionless at the end of the lead with ears up, neck arched and rear stretched to the max, staring at a piece of bait, this is an artificial image of the breed. A better picture of the same dog would be to see him standing at the end of the lead full of energy, in intense observation of something happening around him — he may not be focused on the handler or the judge, but be alert to his surroundings, and be well aware of the handler and the judge.

Doberman handlers are some of the best at the shows. Presentations vary from casual to very intense. Many are experts at stacking, showing teeth, and gaiting, while some are excellent at racing dogs around the ring and stringing them up to try to cover faults. You are in control of your own ring. Have the dog presented the way you want it, not the way the handler wants you to see it.

You should get the same impression of the dog standing and moving. Do justice to the Doberman and move him nice and easy on a loose lead.

1 Start by standing at a distance from the dog, looking at the impression the dog gives you as a whole from a profile view.

-

Is it a medium sized dog, one piece? Does everything flow together? Do you get the impression of a powerful, muscular dog?

-

Is the dog balanced? Is the weight evenly distributed? Does it look like you could push him from any direction and you couldn’t push him off balance?

-

Does any part catch your eye? Does any part stand out, or make you stop and look at it (good or bad)?

- Are all the parts in proportion to each other, is the dog smooth, is the outline pleasing, is the brisket to the elbow, is the tail set correct, is the neck length in proportion to the body, legs, head, does

everything fit?

2 Always approach the dog from the front and look at him asking yourself the same questions you did while viewing the outline from a distance.

-

Do you have the same impression of the dog up close as you did from a distance?

-

Are the legs straight, feet tight and catlike, is there sufficient bone, is there correct width between the legs, is there sufficient depth of brisket, check the shape of the head– is the head a blunt wedge, is there fill under the eye (do you have a muzzle in your hands or air), do you see underjaw, are ears set high, eyes correct (to be sure, have the dog lift his head and look up — a confident dog will look you in the eye) is the dog alert, ask yourself again, do all the parts fit?

-

Many handlers like to hold the ears up. How can you tell where the ears are set?

-

Do NOT bend down in front to check teeth or measure angles. Dobermans are trained to tolerate most anything, but they are inherently watchful and alert. Respect the Doberman. If the dog turns his head towards you on the exam, he is just being curious, not shy.

3 It’s not necessary to have a conversation with a Doberman, a greeting is sufficient — they do not need reassurance. In fact, they may become leery with too much talking.

4 Be firm and definite (not rough) in your approach — if you are leery or approach in a timid manner, they will be suspicious and not want you to get behind them or out of their view.

5 Check the teeth. There are three disqualifications in the mouth, so it is important to know how to check the number of teeth and occlusion. Be sure to check the occlusion from the front and side. First check the mouth with jaws closed, lift the lips and count teeth in the front and each side, then open the mouth a small amount, angle the head up and look at the very back teeth. (a good handler will put fingers in the spaces where teeth should be if they are missing, or let the lips cover the spaces). DON’T COUNT SPACES, COUNT TEETH!!!! Teeth should be large (and clean). Be aware that extra teeth can fill in spaces where teeth are missing, in which case, 42 teeth can still lead to a

disqualification. Remember that the standard states, “42 CORRECTLY PLACED teeth”.

6 Put your hands on the side of the muzzle — if there is good fill, you will have no space between the muzzle and your hands. Continue up the muzzle to the feel the top of the skull where the ears join the head, feel the base of the ears (if you are going to feel strings, it will be here) — continue up the ear.

7 Run your hand down the neck and feel the shoulders, the chest (or lack thereof), down the back, to the tail, feeling the croup. While still maintaining contact with the dog, check for testicles. Feel the coat texture and observe the color.

8 Walk around to the rear of the dog and look down at him from behind. See the width of shoulder, rib and hips (they should be the same). Is there an hour glass shape, does the dog have a barrel shape, or is it flat like a piece of cardboard? Does the neck flow into the shoulder smoothly (wrinkles over the neck?), do the elbows fit tight into the

ribs, again, does it all flow together?

9 Squeeze the thigh to feel for muscle. The Doberman is an athlete and should look and feel like one, with hard muscle and tight skin.

Gaiting —

1 Ask the handler to gait the dog in the pattern you request, but ask the handler to move the dog easy on a loose lead. Tell every handler, every time.

2 Watch the dog move up and back — slowly on a loose lead. Some handlers will string up the dog and move fast to hide poor movement.

3 The legs should tend towards the middle. This is a breed that single tracks, but each dog will do it at a different speed, so they should not move wide.

4 As the dog gaits away, look through the rear and watch the front. As the dog comes towards you, look through the front and watch the rear.

5 While the dog is gaiting, observe the reach and drive (front leg extends as far as the plane of the tip of the nose), is the dog light on his feet, is there any wasted motion? Is the dog balanced while moving? Do the parts fit together? This is the one time you can truly see how the dog is built, handlers can’t lengthen the neck, put the tail where it belongs, fix a bad topline, or underline, and add or subtract to make the parts fit. Observe more than the feet and legs, watch the entire body, how the dog carries himself, keeping in mind that the head should be carried just above the shoulder, not too high. Efficient gait comes from a correctly built dog.

6 When the Doberman gaits, the side gait should look like two scissors

moving in unison. Gaiting is powerful, it should be balanced, with both ends moving in unison. There should be no overreaching/overstriding (when the legs cross in the middle). They should NOT move like a German Shepherd — with extreme, exaggerated reach and drive, which is not typical Doberman movement. The Doberman has moderate angles and therefore should not have an extreme gait. The Doberman should have a moderate, yet powerful gait.

7 The rear should look like it’s moving the dog forward, not just following the front. The hocks should extend, not stay firm (sickle hocks). Sickle hocks and over angulated rears creating extreme (GSD — like) side gait are not typical Doberman gait characteristics and should not be rewarded.

8 One of the most important ways to observe the “General Appearance”, is to see the dog standing on it’s own — without handler contact. Ask the handler to bring the dog to a location in the ring so that you can walk around it and observe it from all directions. . Let the dog stand on his own — don’t allow the handler to hand stack the dog. Observe how the dog puts himself together and not the skills of the handler.

-

Walk up and look into the dog’s eyes, at the expression. If the handler tosses bait do you see expression? Do you see the sparkle in the eye?

-

How does the dog feel about himself?

-

The dog should stop 4 square — this doesn’t mean all the feet have to be perfect — it means the weight should be evenly distributed in the center of the dog. If you pushed him from any direction, he wouldn’t lose his balance.

-

A Doberman being watchful, determined and alert, may not immediately focus on the handler — give them enough time to focus, then finish your exam.

Things to observe while the dog is in motion —

-

Is the dog over reaching? (legs crossing in the middle?)

-

Is the tail carried just above the horizontal or is it straight up?

-

Is the topline level, not lumpy. How does the neck fit into the

shoulder?

-

Is the head carried high or just above the level of the shoulder for efficiency?

-

Does the dog put himself together without the aid of the handler?

-

Do all the parts fit together in one piece or do you notice individual parts of the dog?

-

Did you get the same impression of the dog standing and moving?

-

Does the dog look like an athlete, poured into his skin, one piece, elegant, moderate (not extreme), does the dog feel good about himself?

-

Most of the evaluation should be when the dog is on the move — not basing it only on reach, drive and soundness, but how the parts fit together into a whole package, creating the look of the well balanced,